Ruth Goldstein- Department of Global and International Studies, University of California, Irvine.

(See below for Spanish translation)

“In the neocolonial alchemy, gold changes into scrap metal and food into poison.”

Exiled Uruguayan scholar Eduardo Galeano writes about toxic neocolonial alchemies in the first pages of The Open Veins of Latin America (Las Venas Abiertas de América Latina) (1973: 2). While he would later criticize his book for being too literary and impassioned, his contribution stands as a powerful condemnation of extractive economies of the past that continue into the present. He cites the structural adjustment policies promoted by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund that began in the 1950s. These policies, as part of post-colonial financing schemes, tightened the tourniquet on the open veins of Latin America, changing gold into scrap metal and food into poison.

Images 1-3: Mining in Madre de Dios; Burning Mercury Amalgam; The Madre de Dios River (Source: The image of the mining camps (upper left corner) is used with permission of E. Estumbelo. The other two images were taken by the author).

Image 4: UNEP Guide to Mining with Mercury.

Throughout the Amazon Basin, state-owned and transnational corporations extract natural capital of all kinds: timber, water, oil, gas, and, of course, gold. In the Peruvian Amazonian region of Madre de Dios, Hunt Oil works a land concession in the Harakbut territories (https://ejatlas.org/conflict/amarakaeri-against-hunt-oil) and an estimated 70,000 illegal gold miners (Castro 2018; Fernandez 2019) apply liquid mercury in the process of small-scale and artisanal (ASGM gold mining). The deforestation is extensive, both from illegal logging (https://ojo-publico.com/especiales/madera-sucia/) and from the gold mining (Caballero et al. 2018; Amancio, Nelly Luna 2018) (https://ojo-publico.com/sites/apps/oro-sucio-desastre-en-la-amazonia/). Miners use liquid mercury (quicksilver) to amalgamate the gold particles, pulled from riverbeds and open-mining pits. The excess liquid mercury is poured onto the ground (it is quite cheap). The mercury-gold amalgam is burned to leave pure gold. The vaporous mercury enters the air, and, like the quicksilver, also enters into a cycle of bioaccumulation, affecting fish and the people who eat the fish. One of the most-impacted areas is the Tambopata Nature reserve (https://ejatlas.org/conflict/illegal-mining-in-la-pampa-tambopata-peru).

Indigenous communities in Peru’s Amazon have grown worried about increasingly high levels of mercury, poisoning their food systems, drinking and bathing water, and their air (Hill 2018; Langeland et al. 2018; Reaño 2016 and see https://ejatlas.org/conflict/comunidad-indigenatres-islas-y-mineria-ilegal-en-madre-de-dios). It was thus fitting, then, on November 28, 2019, the day that many people in the United States of North America were celebrating Thanksgiving with food and drink, that a delegation of three Peruvian indigenous leaders shared their concerns about toxicity in their food chain at the United Nation’s third Conference of Parties (COP3) to the Minamata Convention on Mercury. The Convention is the first global environmental agreement negotiated in the 21st century. The aim is to “protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury and mercury compounds” (UNEP 2019: 9). The Minamata treaty outlines a number of measures meant to control the supply-chain of mercury used in products like batteries, lightbulbs, pesticides, cosmetics, and dental amalgams as well as in the practice of ASGM.[1]

The delegation included two indigenous representatives from Peru’s Amazonian region of Madre de Dios: Julio Cusurichi, from the Shipibo community of El Pilar and president of the Native Federation of Madre de Dios (FENAMAD https://www.fenamad.com.pe) and Luis Tayori, from the Harakbut community of Puerto Luz and leader of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve (ECA-RCA https://amarakaeri.org). They were joined by Richard Rubio, from Peru’s Kiwcha community in Loreto and vice-president of Peru’s national Amazonian indigenous organization (AIDESEP http://www.aidesep.org.pe. Three anthropologists accompanied them: Daniel Rodriguez, advisor to FENAMAD, Angela Arriola, advisor to AIDESEP and myself.

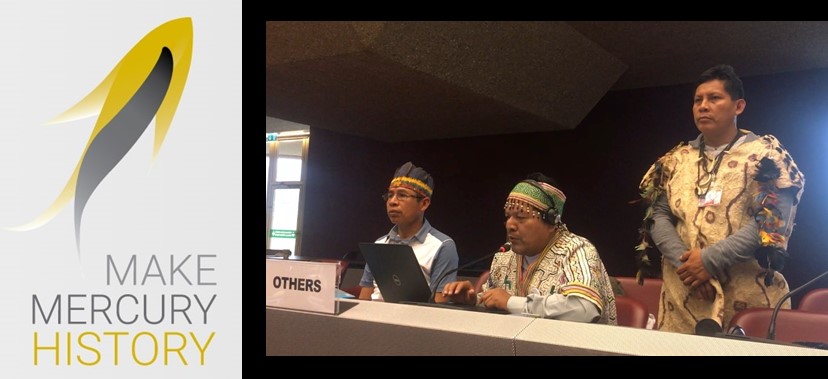

Image 5: “Make Mercury History” (Source: http://www.mercuryconvention.org/)

Image 6: “Others” Plenary Intervention. From left to right: Richard Rubio, Julio Cusurichi, and Luis Tayori. Source: the author.

The Convention’s motto is: “Make Mercury History.” The mere presence of Cusurichi, Rubio, and Tayori made mercury history, in one sense. They were the only indigenous representatives to attend the meetings. Non-governmental parties may request to speak if their prepared statement is relevant to the articles in discussion among the country delegates. The topic was health on Thanksgiving morning. Sitting in the “OTHERS” section for representatives, Cusurichi, a 2008 Goldman Environmental Prize winner, spoke while Rubio, Tayori, and Rodriguez stood behind him in solidarity. Cusurichi outlined the troubling situation in indigenous communities who rely on river fish as a staple of their diet, river fish that now had dangerous levels of mercury in them. Public health information and health care delivery was not reaching indigenous Amazonian people in Peru, he declared, nor were they were consulted in the National Action Plan (NAP). He also asked why indigenous participation on the global level was non-existent when the Convention specifically noted that indigenous and local communities, particularly in areas of ASGM-related activities, were the most impacted by mercury contamination.

The Peruvian delegation in Geneva responded later that day with a public announcement that mercury contamination in indigenous communities was “a complicated matter.”

Since 2011, I have conducted engaged ethnographic research in Madre de Dios, Peru. In 2017, I asked Cusurichi about working on mercury contamination in indigenous communities. In 2019, I was able to support the participation Peruvian colleagues from communities affected by mercury to Geneva as Co-PI on a Coupled Natural-Human Systems (CNHS) National Science Foundation grant (2019-2022), written with atmospheric chemist Noelle Selin (PI) and political scientist Henrik Selin (Co-PI). My role is creating the collaborative ethnographic research design. This means supporting participation of stakeholders affected by mercury contamination – not just indigenous Amazonian community members, but also the miners and sex-workers, primarily coming from the Andes. As with many natural resource extraction jobs, the labor is predominantly male. Sex-work for women comes as a companion industry. These populations are also affected by mercury toxicity – breathing, eating, or touching it daily.

Because quicksilver is so pretty, because multivalent mercury in any of its forms neither smells nor tastes like anything, convincing people of its poisonous effects has been difficult. It’s not just that mercury doesn’t appear dangerous. It helps to produce gold. In the neocolonial alchemy, the process is both chemical and economic – with entangled toxic effects. Economically, mercury is the god of trade. For European colonial powers, the mercantile system is what tapped into the open veins of natural resources. “Toxic assets” are investments that have lost their value and cannot be sold at any price. “Is this what our land will become?” Cusurichi and his colleagues wondered. “What will be left?”

The history of the Minamata Convention stems from the legacy of Japan’s Chisso Chemical Company, which leaked methylmercury into Minamata Bay between 1932 and 1968. Support for survivors has not been sufficient, although the government points to clean-up efforts. Accounts of how birds dropped from the sky, how cats “danced” (Minamata is also called “dancing cat disease)” and then how people became incredibly ill or died. The link: eating sea-life from the contaminated Bay. In 1956, “Minamata disease” entered medical dictionaries (Hachiya 2006) as a “severe permanent neurologic disorder” (Miller-Keane 2003). Symptoms comprise the loss of impulse control, feeling in their limbs, and mental acuity. Seizures are also common.

Indigenous communities around the world are often the hardest hit by toxic levels of mercury – from the Arctic to the Amazon. Not surprisingly, in Peru’s gold-rich Amazonian region of Madre de Dios, mercury is poison entire food-systems, even when people live upstream from gold mining industries (Hill 2018). Researchers from Wake Forest, Stanford-Carnegie, UC Berkeley, and Duke University have conducted studies on the amount of mercury in the bodies of the land, rivers, and humans. Despite sharing this information with the Peruvian government, little effort has been made to educate communities about mercury’s incurable damage. Indigenous Amazonians aren’t the only ones affected by mercury toxicity or left largely out of the policy conversations. While the Peruvian government has made modest efforts to reach the new wave of Andean “colonists” who come from the mountains to the rainforest to mine for gold, they are often not well informed about mercury as a poison either.

As a heavy metal, mercury’s ability to pass the blood-brain barrier and amniotic fluid has contributed to Minamata disease throughout indigenous communities Madre de Dios. Such incidents are often underreported either because the hand-written reports in health posts are doctored, mis-written, or forgotten or because indigenous parents are, understandably, ashamed or mistrusting of government healthcare workers who often come for two-year stints from elsewhere in Peru. Mistrust among indigenous communities has only grown since 2017, when the ministry of health abruptly shut down its indigenous branch (Cabel 2017). FENAMAD and AIDESEP had been key in taking political action, drawing international attention to government’s decision.

As we sat down to our own dinner that evening, we discussed the future. How to reverse the process that turns gold into scrap metal and food into poison? While only a step in remediating the damage, the meetings would end with the Minamata secretariat promising to dedicate funds for indigenous participation at the next conference. Shifting the power dynamics that create toxic economic and social relations – away from extraction to stakeholder interaction – can play a critical role in creating the grounds for making mercury, and mercantile systems, history.

Note: The author thanks Cusurichi, Tayori, Rubio, Rodriguez, Arriola and Ismawati as well as colleagues in the Peruvian Ministry of the Environment for their advocacy efforts as well as the National Science Foundation #1924148 “CNH2-S: Mercury Pollution and Human-Technical-Environmental Interactions in Artisanal Mining,” as well as Noelle and Henrik Selin.

[1] The year 2020 is the deadline to eliminate mercury from these products.

References:

Cabel, Andrea. 2017. “Urgente: SE ELIMINA LA DIRECCION DE PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS DEL MINISTERIO DE SALUD.” LaMula.Pe, March 13. https://deunsilencioajeno.lamula.pe/2017/03/13/urgente-se-elimina-la-direccion-de-pueblos-indigenas-del-ministerio-de-salud/andrea.cabel/ (last accessed February 4, 2020).

Galeano, Eduardo. 1973. The Open Veins of Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Hachiya, Noriyuki. 2006. “The History and the Present of Minamata Disease: Entering the second half a century.” Japan Medical Association 49(3): 112-118.

Hill, David. 2018. “Remote Amazon tribe hit by mercury crisis, leaked report says.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon/2018/jan/24/amazon-tribe-mercury-crisis-leaked-report. The Guardian, Wednesday, January 24. (Last accessed January 21, 2020).

Langeland, Aubrey et al. 2017. “Mercury Levels in Human Hair and Farmed Fish near Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining Communities in the Madre de Dios River Basin, Peru”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14(302): 1-18. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030302

Miller-Keane. 2003. Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. New York: Miller-Keane.

Reaño, Guillermo. 2016. “Ciudad de M. Contaminación por mercurio en Madre de Dios.” March 22. http://soloparaviajeros.pe/denuncia-ciudad-de-m-contaminacion-por-mercurio-en-madre-de-dios/ (last accessed January 25, 2020).

UNEP 2018. Minamata Convention on Mercury: Text and Annexes. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations.

“Digamos Adiós al Mercurio”: Activos Tóxicos y Extracción Neocolonial

Ruth Goldstein– Departamento de Estudios Globales e Internacionales, Universidad de California, Irvine.

Traducción facilitada por Daniel Rodríguez

“En la alquimia neocolonial, el oro se convierte en chatarra y la comida en veneno.”

Durante su exilio, el intelectual uruguayo Eduardo Galeano escribió sobre las alquimias tóxicas neocoloniales en las primeras páginas de Las Venas Abiertas de América Latina (1973: 2). Aunque el autor llegaría a criticar su libro por ser demasiado literario y efusivo, la obra continúa siendo una poderosa denuncia de la continuidad histórica de las economías extractivas hasta el presente. Una referencia que señala son las políticas de ajuste estructural promovidas por el Banco Mundial y el Fondo Monetario Internacional iniciadas en la década de 1950. Esas políticas, como parte de los sistemas de financiamiento post-coloniales, apretaron el torniquete en las venas abiertas de América Latina, transformando el oro en chatarra y la comida en veneno.

Imágenes 1-3: Minería en Madre de Dios; Quema de amalgama de mercurio; El Río Madre de Dios. Fuente: La imagen de los campamentos mineros (esquina superior izquierda) se utiliza con permiso de E. Estumbelo. Las otras dos imágenes son de la autora.

Imagen 4: Guía del Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente – PNUMA para la reducción del uso de mercurio en la minería artesanal y a pequeña escala. Fuente: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/11524/reducing_mercury_artisanal_gold_mining.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

En toda la extensión de la Amazonía, empresas estatales y corporaciones transnacionales extraen recursos naturales de todo tipo: madera, agua, petróleo, gas, y, por supuesto, oro. En la región de Madre de Dios de la Amazonia Peruana, la Hunt Oil tiene una concesión sobre el territorio del pueblo Harakbut, y se estima que unos 70,000 mineros ilegales (Castro 2018; Fernandez 2019) utilizan mercurio líquido o “azogue” en actividades de extracción aurífera artesanal y a pequeña escala o “ASGM”[1]. La deforestación es intensa, tanto por la tala ilegal como por la minería (Caballero et al. 2018; Amancio, Nelly Luna 2018). Los mineros utilizan el mercurio líquido (azogue) para amalgamar las partículas de oro extraídas en lechos de ríos y áreas a cielo abierto. El mercurio líquido tiene un precio relativamente asequible por lo que su exceso suele liberarse al ambiente. La amalgama de mercurio se quema para rendir el oro puro. El mercurio que se evapora, al igual que en su forma líquida, entra en un ciclo de bio-acumulación, afectando a los peces y las personas que los consumen. Una de las áreas más impactadas es la Reserva Nacional Tambopata.

Las comunidades indígenas en la Amazonía Peruana están cada vez más preocupados por los altos niveles de mercurio que contaminan sus fuentes alimentarias, el agua, y el aire (Hill 2018; Langeland et al. 2018; Reaño 2016 y ver también). Era una linda ironía, entonces, que el 28 de noviembre de 2019, el día en el que mucha gente en los Estados Unidos celebraba el día de Acción de Gracias con comida y bebida, una delegación de tres líderes indígenas de dicha región presentara su preocupación por la contaminación de sus fuentes de alimento ante las Naciones Unidas, en el marco de la tercera reunión de la Conferencia de las Partes del Convenio de Minamata sobre el mercurio (COP3). Este convenio es el primer acuerdo ambiental global negociado en el siglo XXI. Su objetivo es “proteger la salud humana y el medio ambiente de las emisiones y liberaciones antropógenas de mercurio y compuestos de mercurio” (PNUMA[2] 2019: 9). El tratado de Minamata define un numero de medidas para controlar las cadenas de suministro de mercurio utilizado en productos como baterías, focos, pesticidas, cosméticos y amalgamas dentales, así como también en actividades ASGM[3].

La delegación incluía a dos representantes indígenas de la región de Madre de Dios de la Amazonía Peruana: Julio Cusurichi, de la comunidad Shipibo de El Pilar y presidente de la Federación Nativa del río Madre de Dios y Afluentes – FENAMAD, y Luis Tayori, de la comunidad Harakbut de Puerto Luz y líder del Ejecutor de Contrato de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri – ECA-RCA. El grupo incluía también a Richard Rubio, del pueblo Kichwa de Loreto y vicepresidente de la Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana – AIDESEP. Acompañando a los líderes indígenas, estábamos también tres antropólogos: Daniel Rodríguez, asesor de FENAMAD, Ángela Arriola, asesora de AIDESEP, y mi persona.

Imagen 5: “Digamos Adiós al Mercurio”. Fuente: http://www.mercuryconvention.org/

Imagen 6: Intervención en la plenaria de los “Otros”. De izquierda a derecha: Richard Rubio, Julio Cusurichi, y Luis Tayori. Fuente: la autora.

El lema del Convenio es: “Digamos Adiós al Mercurio”, adaptación del inglés original “Make Mercury History“. La mera presencia de Cusurichi, Rubio, y Tayori fue, en cierto modo, histórica. Ellos fueron los únicos representantes indígenas que participaron de las reuniones. Las instituciones no gubernamentales participantes en el evento pueden solicitar realizar una intervención en la plenaria, si el texto de su declaración se considera relevante en relación a los artículos en discusión de los delegados de los países. Aquella mañana del día de Acción de Gracias el tema era la salud y el mercurio. Sentado en la sección “OTROS” (reservada para actores no gubernamentales), Cusurichi, Premio Medioambiental Goldman en 2007, realizó su intervención ante la plenaria, mientras Rubio, Tayori, y Rodríguez, permanecían de pie a su lado en señal de solidaridad. Cusurichi describió la preocupante situación de las comunidades indígenas, enfatizando la afectación de su fuente básica de alimentación, el pescado, en el que se registran peligrosos niveles de mercurio. Cusurichi denunció también que los pueblos indígenas en la Amazonía Peruana no reciben información adecuada sobre este tema por parte de las autoridades de salud, y que tampoco fueron consultados en la elaboración del Plan de Acción Nacional para la implementación del Convenio. Finalmente, Cusurichi cuestionó la falta de participación indígena en la COP pese a que el texto del Convenio señala que los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales son las más impactadas por la contaminación por mercurio, particularmente en áreas donde se desarrollan actividades ASGM.

Más tarde, ese mismo día, la delegación peruana en Ginebra respondería a estas críticas señalando que la contaminación por mercurio en las comunidades indígenas era “un asunto complicado”, aunque finalmente admitió que existía la necesidad de responder directamente a los pueblos afectados.

Desde hace ya casi una década realizo trabajo de investigación etnográfica en la región de Madre de Dios. En 2017, propuse a Cusurichi trabajar sobre la contaminación por mercurio en las comunidades indígenas. En 2019, conseguí apoyo para la participación de la delegación indígena peruana en la COP3 del Convenio de Minamata en Ginebra, a través de una beca del Programa Coupled Natural-Human Systems (CNHS), de la National Science Foundation. El trabajo es dirigido por la química atmosférica Noelle Selin (investigadora principal), además del politólogo Henrik Selin y mi persona (co-investigadores). En particular, mi papel es crear un diseño de investigación etnográfica colaborativa. Esto significa apoyar la participación de actores afectados por la contaminación por mercurio – no solamente miembros de comunidades indígenas Amazónicas, sino también otros, como extractores y trabajadoras sexuales, provenientes principalmente desde la región Andina. Como en la mayoría de las actividades extractivas, el trabajo es realizado principalmente por hombres. El trabajo sexual de las mujeres aparece como una economía asociada a la anterior. Dichas poblaciones también son afectadas por la toxicidad del mercurio – al respirarlo, ingerirlo o manipularlo diariamente.

Dado el atractivo aspecto del mercurio líquido, y ya que este elemente carece de olor y sabor en cualquiera de sus formas, convencer a la gente de sus efectos tóxicos es una tarea difícil. Pero no es solamente que el mercurio no tenga apariencia peligrosa. También sucede que es un elemento clave en la obtención del oro. En la alquimia neocolonial, el proceso es tanto químico como económico – con efectos tóxicos inherentes. Económicamente, el mercurio es el dios del mercado. Para los poderes coloniales europeos, el sistema mercantil “abría las venas” de los recursos naturales. “Activos tóxicos” son inversiones que han perdido su valor y que carecen de precio de venta. “¿En esto se va a convertir nuestro territorio?”– se preguntaban Cusurichi y sus compañeros: “No va a quedar nada”.

La historia del Convenio de Minamata parte del trágico legado de la Corporación Chisso, la empresa química japonesa que liberó grandes cantidades de metilmercurio a la bahía de Minamata entre 1932 y 1968. El apoyo a los supervivientes de dicha catástrofe no ha sido suficiente, aunque el gobierno destaca sus esfuerzos de remediación. De aquel dramático episodio quedan aún testimonios de aves cayendo desde el cielo, de gatos “danzando”[4], y de cómo la gente se enfermaba gravemente o moría. El origen: el consumo de fauna marina de la bahía contaminada. En 1956, la “Enfermedad de Minamata” se incluye en los diccionarios médicos (Hachiya 2006) como una “severa afección neurológica permanente” (Miller-Keane 2003). Los síntomas incluyen la pérdida de control de los impulsos, sensibilidad en las extremidades y agudeza mental. Las convulsiones son también comunes.

En distintas partes del mundo, los pueblos indígenas suelen ser las poblaciones más afectadas por niveles tóxicos de mercurio – desde el Ártico a la Amazonía. No sorprende entonces que en la región de Madre de Dios de la Amazonía Peruana, donde se desarrolla una intensa actividad extractiva de oro aluvial, el mercurio haya contaminado la cadena alimentaria, afectando incluso a poblaciones que viven a grandes distancias de las áreas de minería aurífera. Investigadores de las universidades de Wake Forest, Stanford-Carnegie, UC Berkeley, y Duke han realizado estudios para medir niveles de mercurio en ecosistemas terrestres, acuáticos y poblaciones humanas. A pesar de que los resultados de estas investigaciones han sido compartidos con el gobierno peruano, las acciones oficiales para informar y sensibilizar a las comunidades sobre los graves riesgos del mercurio han sido insuficientes. Los pueblos indígenas amazónicos no son los únicos afectados por la toxicidad del mercurio o ignorados en el desarrollo de políticas públicas. Aunque desde las autoridades gubernamentales ha habido un cierto esfuerzo para aproximarse a la nueva oleada de “colonos” andinos llegados desde la sierra a la selva en busca de oro, esta población tampoco está bien informada sobre los riesgos del mercurio.

Siendo un metal pesado, la capacidad del mercurio para pasar del torrente sanguíneo al sistema nervioso y al líquido amniótico, implica la existencia de riesgos de que la enfermedad de Minamata afecte a la población indígena en Madre de Dios. Generalmente, ese tipo de casos no son reportados, ya sea porque los reportes son adulterados, mal escritos u olvidados, porque lxs trabajadorxs de salud del Estado no son suficientes, o porque el Estado Peruano todavía no tiene un plan de salud eficaz para identificar, monitorear, y responder a las enfermedades vinculadas con la contaminación por mercurio. Además, las comunidades indígenas, comprensiblemente, muchas veces se sienten avergonzadas por padecer síntomas que no entienden, además de sentir desconfianza ante trabajadorxs de la salud llegados desde otros lugares del país.

La desconfianza entre las comunidades indígenas creció aún más en 2017, cuando el Ministerio de Salud decidió eliminar la dirección específica de pueblos indígenas (Cabel 2017). La respuesta de FENAMAD, AIDESEP y otras organizaciones denunciando dicha medida fue decisiva para lograr su revocación y conseguir la reactivación de la institución.

Volviendo al día de la conferencia, mientras cenábamos por la noche conversamos sobre el futuro. “Como revertir el proceso que convierte el oro en chatarra y el alimento en veneno?” Aunque fue solo un paso hacia la remediación del daño, las reuniones de la COP3 concluyeron con el compromiso del secretariado del Convenio de Minamata de impulsar la participación indígena en la próxima edición. Cambiar las dinámicas de poder que crean las relaciones toxicas en el ámbito económico y social – desde la extracción de los recursos naturales a la interacción con las personas afectadas – podría jugar un papel crítico en crear las bases para decir adiós al mercurio y los sistemas mercantiles.

Nota:

La autora agradecece por sus esfuerzos a Cusurichi, Tayori, Rubio, Rodriguez, Arriola, Ismawati, a los funcionarios públicos del Ministerio del Ambiente de Perú, así como también a la National Science Foundation #1924148 “CNH2-S: Mercury Pollution and Human-Technical-Environmental Interactions in Artisanal Mining,” y a sus colegas Noelle y Henrik Selin.

[1]Como abreviatura de “minería aurífera artesanal y a pequeña escala” se utiliza frecuentemente el término “ASGM”, que son las siglas en inglés de“Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining”.

[2] PNUMA son las siglas del Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente

[3] El plazo establecido para la eliminación del mercurio de dichos productos es el año 2020.

[4] La enfermedad de Minamata se conocía también como la “fiebre del gato bailando”.

References:

Cabel, Andrea. 2017. “Urgente: SE ELIMINA LA DIRECCION DE PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS DEL MINISTERIO DE SALUD.” LaMula.Pe, March 13. https://deunsilencioajeno.lamula.pe/2017/03/13/urgente-se-elimina-la-direccion-de-pueblos-indigenas-del-ministerio-de-salud/andrea.cabel/ (last accessed February 4, 2020).

Galeano, Eduardo. 1973. The Open Veins of Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Hachiya, Noriyuki. 2006. “The History and the Present of Minamata Disease: Entering the second half a century.” Japan Medical Association 49(3): 112-118.

Hill, David. 2018. “Remote Amazon tribe hit by mercury crisis, leaked report says.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon/2018/jan/24/amazon-tribe-mercury-crisis-leaked-report. The Guardian, Wednesday, January 24. (Last accessed January 21, 2020).

Langeland, Aubrey et al. 2017. “Mercury Levels in Human Hair and Farmed Fish near Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining Communities in the Madre de Dios River Basin, Peru”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14(302): 1-18. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030302

Miller-Keane. 2003. Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. New York: Miller-Keane.

Reaño, Guillermo. 2016. “Ciudad de M. Contaminación por mercurio en Madre de Dios.” March 22. http://soloparaviajeros.pe/denuncia-ciudad-de-m-contaminacion-por-mercurio-en-madre-de-dios/ (last accessed January 25, 2020).

UNEP 2018. Minamata Convention on Mercury: Text and Annexes. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations.