Peyman Jafari, Princeton University & International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam).

During the last two decades, Iran has developed a significant petrochemical sector. Whenever it makes headlines, however, the reason is often international politics. In June 2019, for instance, the Trump administration imposed severe sanctions on the Persian Gulf Petrochemical Industries Company (PGPIC) due to its alleged ties with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). In reality, the reason has more to do with the significance of PGPIC for Iran’s economy, which the US has tried to choke through economic sanctions. The reason is simple, the PGPIC group “holds 40% of Iran’s total petrochemical production capacity and is responsible for 50% of the country’s petrochemical exports,” as the US Treasury mentions in its statement.[1] The geopolitical significance of Iran’s petrochemical industry was also visible most recently on 8 November, when Iran shot down an unidentified drone near the port of Bandar-e Mahshahr, on the south-western shore of the Persian Gulf, where the Mahshahr Petrochemical Special Economic Zone is located.[2]

In the Iranian news, the petrochemical industry has made headlines more frequently, though for very different reasons. One reason is the popularity of the petrochemical complexes among state officials who visit them regularly to showcase Iran’s latest economic and technological advancements to the domestic audience. On 4 September 2018, for instance, President Hassan Rouhani visited Asaluyeh for the inauguration of three petrochemical plants. A journalist of the Aftab-e Yazd newspaper reported that some of the inhabitants complained that during his visit the sky was bluer than otherwise, because the gas flares of the gas and petrochemical plants had been lowered to diminish pollution.[3] This points to the second reason why Iran’s petrochemical industry is frequently covered in the domestic media. Parallel to the growth of the petrochemical industry, there has been an avalanche of complaints about pollution and the dismal social conditions that have afflicted workers and fence communities of the petrochemical industry in Asaluyeh. Unlike its exceptional geostrategic predicament, the creation of pollution, labour precarity and social exclusion by the petrochemical industry are not exclusively Iranian problems; they rather characterise the global petrochemical industry.

Asaluyeh: Iran’s Energy Capital

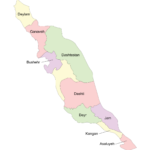

Before discussing these problems, I will first provide a brief overview of the growth of the petrochemical industry in Asaluyeh. My previous research on the social history of labour in the Iranian oil industry focused on the city of Abadan.[4] Located at the furthest western corner of Iran’s coastline of the Persian Gulf, Abadan developed into the region’s industrial hub after oil was discovered in 1908. The refinery in Abadan became the biggest in the world in the following decades. Anyone who visits Abadan today, however, will notice that the refinery and the city have become a shadow of their past, particularly due to the destruction caused during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88). The war forced the authorities to relocate Iran’s petroleum production and export facilities land inwards, and eastwards along the Persian Gulf. After the war ended in 1989, the fossil energy-related industrial activities gradually shifted further to the east along the coast, towards the Bushehr province (Figure 1). This reflected the growing importance of gas and petrochemical production, which were intimately interlinked as gas provided the feedstock for the petrochemical industry.

The impetus for this development came mainly from the discovery of South Pars/North Field, the world’s largest gas field, which lies in the Persian Gulf between Iran and Qatar. When the development of the South Pars field started in 1998, 28 refinery projects, referred to as phases, and 30 petrochemical projects were envisioned.[5] Most of the gas and petrochemical plants have been completed and manufacture a variety of products, most importantly gas condensates, liquid gas (propane and butane), rubber and plastics, synthetic fibres, fertilisers, pesticides and polymers.

In 1998, the Pars Oil and Gas Company was created to lead the development of South Pars and the Pars Special Economic Energy Zone (SPEEZ) was designated as the area (14,000 hectares) in and around the Asaluyeh district of Bushehr province (Figure 2), where the gas from South Pars enters through pipelines and is processed. The petrochemical complexes are led by the state-owned National Petrochemical Company (NPC), but private companies are involved as well, including: Tamin Petroleum & Petrochemical Investment Company, Persian Gulf Petrochemical Industries Company, Persian Oil & Gas, Jam Petrochemical, Kharg Petrochemical and Ghadir Investment Company (see Asaluyeh on the Global Petrochemical Map).

The establishment of PSEEZ transformed the spatial, social and ecological organisation of the region. Until the 1990s, the livelihoods of Asaluyeh’s inhabitants were based on fishing, agriculture and petty trade. The population of Asaluyeh district increased from 30,000 in 1996 to nearly 60,000 a decade later, and reached 74,000 in 2016. In the last decade, however, most of the workers that were employed in Asaluyeh’s petrochemical industry settled in Jam, a district to the northwest of Asaluyeh (Figure 2). As a result, Jam’s population grew from 51,446 in 2011 to 70,051 between 2006 and 2016.[6]

Asaluyeh, however, is not only a site of booming economic activities; it is above all a social and ecological disaster zone that has affected its workers and the fenceline communities due to the convergence of two trends – precarisation of the labour force and the pollution of air, water and land.

Precarious labour

From 1998, tens of thousands of workers came to Asaluyeh to construct the gas and petrochemical plants, and about 60,000 workers are currently employed there in construction projects, transport, refineries, the petrochemical plants, and the port. These include both unskilled and semi-skilled workers, as well as technicians and engineers.

PSEEZ was established under the regulations of “special economic zones”, which were established in the 1990s to stimulate industrial development, attract foreign capital and boost exports. They started as “zones of exception” that introduced neoliberal regimes of labour relations in the context of capitalist globalisation.[7] These neoliberal relations were a departure from the populist policies of the 1980s, which had provided a considerable level of protection for Iranian workers in the formal sector, for instance against layoffs, and had diminished the gap between blue-collar and white-collar workers.[8]

The exceptionality of PSEEZ is based on the fact that the employment regulations governing it are exempt from the Labour Law, which, for instance, allows the creation of labour organisations, even if these lack genuine independency in the “normal” zones. Although the employment regulations of the “special economic zones” stipulate that the regulations of the ILO, including the right to organise collectively, should apply, these are disregarded.

Privatisation and outsourcing have added to the precarity of labour conditions in Asaluyeh, as over one thousand subcontractors are involved in PSEEZ. These subcontractors compete with each other by lowering the cost for their clients – Pars Oil and Gas Company and other subsidiaries of the National Iranian Oil Company.

As a result, most workers are employed on temporary contracts that sometimes last only 20 or 30 days. Most of them are not insured, although the organisation of PSEEZ has the responsibility to create insurance funds for them. They work under exceptionally difficult conditions as temperatures can rise to 60 Celsius degrees, and job-related accidents frequently result in deaths. On 15 August, for instance, a worker died and another was injured in one of Asaluyeh’s petrochemical plants.[9]

Although most workers are recruited from areas far from Asaluyeh, the majority of them have short breaks of only one week after working three weeks. The working hours are long as well, between 12 and 16 hours. As one contract worker in Asaluyeh explained: “Every morning, we punch our cards at 6.45 am for breakfast and start at 7.45 in the petrochemical plant. We finish at 7.30 pm and are picked up by the transport service that takes us to our dorms. We work 14 (sic) hours but are only paid for 8.”[10]

The regulations regarding layoffs are often disregarded as well, as a worker in a petrochemical plant in Asaluyeh recounts: “One day, someone suddenly came and said ‘We have a reorganisation plan and have to let some of you go.’ The next day, they put a guard in front of the entrance and stopped me and a few other workers. They told us ‘You are sacked’ and took us one by one on a motorcycle to the finance room for checkout. We had to sign a paper but didn’t receive our wages.”[11]

Moreover, the housing facilities are substandard, forcing 10 workers to live in apartments of just 40 square metres, and there are almost no facilities such as cinemas and sport halls for workers’ leisure time. Yet the biggest problem for most workers is the non-payment or delayed payment of wages by subcontractors, which leads to regular labour protests in Asaluyeh (Figure 3).

- Figure 3 – Workers’ protest in Asaluyeh, May 2018. Source: www.radiozameneh.com

Resistance, which either is repressed or dissipates due to the lack of organisations that can sustain it, is not the only way in which workers react to their harsh conditions. Many have taken their refuge in drug addiction, which has become a serious problem in such regions, and one of the grievances among the fenceline communities of Asaluyeh.

Polluted Environment

According to ’Isa Kalantari, the director of the Department of Environment since August 2017, the average life expectancy of the population of Asaluyeh has shortened by 9 years.[12] Various studies of the water, air and land of Asaluyeh have shown that the pollution caused by the petrochemical and gas industry in this region is significantly higher than elsewhere. This is caused by atmospheric particulate matters (PM2.5 and PM10), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), heavy metals such as lead and cadmium, hazardous air pollutants including nickel, chromium, cadmium, selenium, benzene, hexane, toluene, xylene, propylene, and naphthalene.[13]

The pollution of the Persian Gulf waters around Asaluyeh is due to leaking from pipelines, the dumping of petrochemical waste and sewage water and desalination. According to Maryam Ghaemi, the director of the Iranian National Institute for Oceanography and Atmospheric Science, the waters of the Persian Gulf near oil and gas installations are becoming acidic and this slows the growth of calcium carbonate structures on which calcifying organisms like corals and shells depend. It is estimated that 5 million barrels of oil annually leak into the Persian Gulf from pipelines, oil platforms and ships.[14]

In 2017, Scanex Group and the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IO RAS) conducted satellite monitoring of oil pollution in the Persian Gulf: “The total area of the detected pollution is found to be 13,835 sq. km. The area of individual spills varied from 0.5 to 600 sq. km. Oil pollution of anthropogenic origin in the Persian Gulf was found almost everywhere… The vast majority of oil spills is associated with oil and gas production areas, as well as with major shipping routes, some of which run along the long axis of the Gulf and connect large oil terminals and ports. Anomalously large oil spills (240 to 780 sq. km) were detected in the Iranian sector of the Gulf (south off Siri Island) in mid-March 2017 when an emergency discharge occurred at an oil well/platform at the Siri-E oilfield (Fig. 2). According to the SkyTruth experts, 300 to 620 m3 of oil and/or oil products were spilled into the sea.”[15]

Conclusion

The economic development of the petrochemical industry in Iran has been considerable since the late 1990s, but this development has been accompanied by serious social and ecological problems. Outside Iran, these problems have been often obscured by the geopolitical tensions that shape the news about Iran’s petrochemical industry. Inside Iran, these problems are often regarded as the outcome of Iran’s “unique” political and economic power structures that facilitate corruption through, for instance, the involvement of subcontractors. There is, however, an urgent need to highlight the social and ecological problems that surround the petrochemical industry, and to study these from a global perspective that discloses the commonalities and differences between the socio-ecological consequences of the petrochemical industry in Iran and elsewhere.

[1] The Guardian, “US Imposes Sanctions on Iran’s Largest Petrochemical Group,” 8 June 2019. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/08/us-imposes-sanctions-on-irans-largest-petrochemical-group

[2] The Guardian, “Unidentified Foreign Drone Shot down in Iran, Say News Agencies”, 8 November 2019. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/08/unidentified-foreign-drone-shot-down-in-iran-state-news-agencies

[3] Aftab Yazd, “Asman-e Asaluyeh abi hast faghat vaghti maghamat miayand” [The sky of Asaluyeh is only blue when officials come over], 18 Shahrivar 1398/9 September 2019. Retrieved from http://aftabeyazd.ir/?newsid=115954

[4] Peyman Jafari, “Oil, Labour and Revolution: A Social History of Labour in the Iranian Oil Industry, 1973-1983” (Leiden Univeristy, 2018). See https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/66125?_ga=2.115989894.1431332915.1573263169-1190968250.1569850906

[5] http://www.pseez.ir/fa/employment/management-درباره

[6] Statistical Center of Iran, Census of Bushehr Province, 1996, 2006, 2016.

[7] Aihwa Ong, Neoliberalism as Exception : Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty (Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2006).

[8] On this transition, and the labor conditions in Asaluyeh see Azam Khatam, “’Asaluyeh Dar Ayineh-Ye Abadan: Az Sherkat-Shahr Ta Ordugah-Ha-Ye Karkonan-e Naft Dar Iran [Asaluyeh in the Mirror of Abadan: From Company Towns to Camps for the Employees of the Iranian Oil Industry],” Goftogu, no. 60 (2012): 56–80; Mohammad Maljoo, “The State of Labor in Iran’s Oil and Petrochemical Industry,” FRONTLINE – Tehran Bureau, June 5, 2011, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2011/06/the-state-of-labor-in-irans-oil-and-petrochemical-industry.html.

[9] ILNA, 24 Mordad 1398/15 August 2019, news ID: 798379.

[10] Andisheh Nou, “Ravayat-e talkh-e zendegi-ye kargarni ke dar Asaluyeh az sakhti-ye kar va bipuli be e’tiyad panah mibarand” [The bitter tale of the life of workers in Asaluyleh who take refuge in drugs due to harsh working conditions and poverty], 20 Aban 1396/11 November 2017. Retrieved from http://andisheh-nou.org/?p=10286 (accessed on 2 September 2019).

[11] Andisheh Nou, “Ravayat-e talkh-e zendegi-ye kargarni ke dar Asaluyeh az sakhti-ye kar va bipuli be e’tiyad panah mibarand” [The bitter tale of the life of workers in Asaluyleh who take refuge in drugs due to harsh working conditions and poverty], 20 Aban 1396/11 November 2017. Retrieved from http://andisheh-nou.org/?p=10286 (accessed on 2 September 2019).

[12] Andisheh Nou, “Kargaran az ranj va tab’iz-ha dar Asaluyeh miguyalnd [Workers speak about suffering and discrimination in Asaluyeh,” 9 Ordibehesht 1398/29 April 2019. Retrieved from http://andisheh-nou.org/?p=18119 (accessed on 2 September 2019).

[13] Saeed Kashmiri et al., “Barresi-ye aludegiha-ye zistmohiti-ye nashi az sanaye’ gaz va petroshimi va asrat-e an bar salamat-e sakenin-e mantaqeh-ye Asaluyeh, paytakhte energy-ye Iran: yek motale’eh-ye moruri [Environmental Pollution Caused by Gas and Petrochemical Industries and Its Effects on the Health of Residents of Assaluyeh Region, Irani-an Energy Capital: A Review Study],” Iran South Med J. 21, no. 2 (2018): 162–85.

[14] Eqtesad Online, “Khalidj-e fars dar dam hayula-ye nafti” [The Persian Gulf in the trap of the oil monster], 17 Mehr 1398/8 October 2019, news ID: 386178.

[15] http://www.scanex.ru/en/company/news/satellite-monitoring-of-oil-pollution-in-the-persian-gulf/