Dayna Nadine Scott, Associate Professor & York Research Chair in Environmental Law & Justice in the Green Economy, York University.

Header image credit: Allan Lissner, PraxisPictures. Source: Neskantaga: We Love Our Land — PraxisPictures

A quiet struggle has been playing out in Ontario’s far north as a wave of Indigenous cultural and political resurgence collides with a renewed push to extend the extractive frontier into the vast, swampy boreal forest. Centered around the much-hyped “Ring of Fire” mineral deposits and the resistance of remote Anishinaabe and Anishini communities that depend on the cultural and ecological integrity of the Attawapiskat river watershed, the stakes in this struggle are high. The social, political, and ecological changes that will come with the extraction of minerals in the Ring of Fire are irreversible, and the resources in contention include so-called “critical minerals” — those that have been deemed necessary for the very transition from fossil fuels that climate justice demands.

In following this struggle over the past five years, I have come to understand it as a microcosm for how the contemporary settler state primes an extractive frontier, even into the so-called ‘post-extractive’ moment.

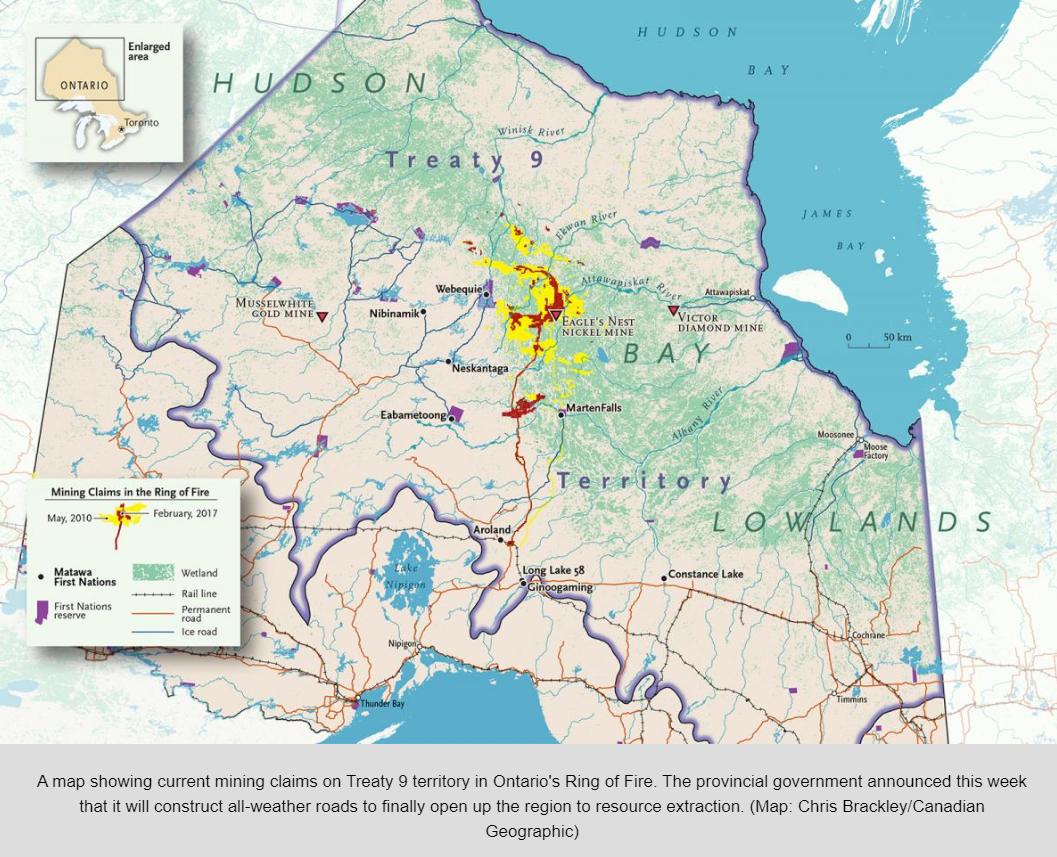

The “Ring of Fire” is a massive, crescent-shaped deposit of minerals, including nickel, copper, zinc, gold, and mostly notably chromite in the far north of Ontario, in central Canada (see map). The minerals are said to lie close to the Earth’s surface in this vast expanse of soggy muskeg and peat bogs dotted with black spruce, jack pine and white birch. The region is home to several iconic boreal creatures such as caribou, lake sturgeon and wolverines; it is said to be perhaps the largest intact boreal forest remaining in the world, a globally significant wetland, and a massive carbon storehouse. It is, most importantly, a landscape that has sustained the lifeways of Anishinaabe and Anishini peoples since time immemorial.

Source: https://republicofmining.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Canadian-Geographic-Map-Treaty-9-Ring-of-Fire.png

Despite the near continuous pressure from exploration companies, if a major mining hub did materialize, it would represent a wild departure from the current reality. Except for the now-closed De Beers’ Victor mine, an open-pit diamond mine midway up the James Bay coast near Attawapiskat, Ontario’s far north has been basically “off-limits” to major industry. The discovery of a commercially-viable source of chromite in the Ring of Fire has — for well more than a decade now — been said to be on the verge of changing that. Chromite is a relatively rare but necessary component of stainless steel not produced anywhere else in North America. But chromite is not like diamonds; getting value from it will involve the hauling of massive quantities of heavy ore, meaning major new infrastructure will be necessary.

Recently, proponents of mining in the region have begun positioning the extraction in the Ring of Fire as a necessary part of the coming “energy transition”, emphasizing that “critical minerals” are needed for the new ‘clean tech’ and digital economy. Nickel, copper and cobalt are important components of electric vehicle batteries, and junior mining companies are looking to ‘plug into’ the growing demand. The region has thus taken on the sheen of a “new frontier” for extraction, even as it is experiencing a resurgence of Indigenous cultural identity.

The communities that have the most at stake in the extraction of minerals and the associated infrastructure in the Ring of Fire are small, remote, Anishini and Anishinaabe communities in a constant state of social emergency, enduring what many Indigenous leaders call “an ongoing genocide”. They are struggling to overcome the trauma of residential schools and government-run day schools, a legacy that includes a rupture in intergenerational transmission of language and laws, land and kinship relations. All of these impacts are compounded by continuing colonial relations and decades of state underfunding of basic services, which is manifest in youth suicide and addiction crises, and a persistent lack of access to safe drinking water. It is hard to look at the situation without concluding that this is how the settler state primes an extractive frontier: the communities are being ‘starved out’ such that capitulating to mining starts to seem like the only way out. They are in a state of permanent anticipation of the major changes that are promised to be coming, yet their daily existence is marked by a distinct lack of any meaningful progress towards mitigation of the ongoing social emergency.

So the new spin on extraction in the Ring of Fire casts the mineral deposits as “critical” to the energy transition and a clean economy. The emerging narrative is one of inclusion and partnership, a progressive corporate plan for bringing ‘Canada’s First Nations’ into prosperity by enlisting them in the production of batteries for electric cars. How should we, as critical scholars, think about “extraction” in this new shade of green? It’s clear that the new green economy will have its “sacrifice zones” just as the fossil era did – that there are, and will continue to be, disparities in relation to who will reap the benefits and who will shoulder the burdens of our collective efforts to meet our needs and wants. By what logic do we determine those distributions? ‘Extractivism’, as I have argued recently, has its own logic: it is a particular way of relating to nature and other beings. It is a mode of accumulation that insists on fast high paced and large scale ‘taking’. It tends to be very effective at generating profits for distant capital without producing much in the way of benefits for local people. It is an orientation to lands and waters that is non-reciprocal and short-term. Extractivism’s logic is endemic to and intensifying under contemporary global capitalism, but it draws on very long colonial history. How do we overcome this logic? I take inspiration from Ontario’s far north, where one community is adopting a politics of refusal.

A Politics of Refusal

In Mohawk political anthropologist Audra Simpson’s conception, refusal is an alternative mode of politics and practice, in critical relationship to the state. Neskantaga First Nation is a community currently engaged in this politics. As Allan Lissner’s incisive documentary demonstrates, Anishinaabe people there consistently articulate a love of their land, a kinship with the Sturgeon of the Attawapiskat River, an intention to fulfill their collective obligations to protect that river, and a fierce defence of their political authority to decide their future. They are actively defending their inherent jurisdiction on their homelands. How they typically frame it is to say: “Everything that happens in our territory, will happen on our terms”. In just one example, a former Chief and elder Peter Moonias has stated repeatedly that he will lay down his life before he lets anyone cross the Attawapiskat River to get to a mine. As he told Cliffs Natural Resources in 2012: “They’re going to have to cross that river, and I told them if they want to cross that river, they’re going to have to kill me first. That’s how strongly I feel about my people’s rights here”.

But the longer the holdout communities resist, the more frantic the state and industry become. Ontario’s exasperated Minister of Energy, Northern Development and Mines stated early in 2020 that “It cannot take us eight years to open up a friggin mine!” to cries of “amen” from a mining industry audience. Similarly, Ontario’s current Premier Doug Ford tweeted during his election campaign that he would kickstart mining in the Ring of Fire even if he had to ‘hop on the bulldozer himself’. When one of the northern Chiefs pointed out that the Premier might require some local guidance to avoid sinking in the muskeg, it foreshadowed a much larger and more profound debate about who actually has the knowledge, the authority, and the jurisdiction to govern Ontario’s far north.

The dynamics of resource extraction in the region are largely, and increasingly, shaped by what I call “extraction contracting” — the negotiation of private contractual agreements. These exist in a variety of forms: they include resource-revenue sharing deals between tribal councils and the provincial government, impact-benefit agreements (IBAs) between communities and companies, early exploration agreements and MOUs, and various agreements with governments and agencies over infrastructure or environmental assessment funding, among others. In all cases, the negotiations are secretive and give rise to a dynamic of competition between neighboring communities, the imposition of settler logics and external timelines, and the dominance of lawyers. In all cases, the signed deal has become a “stand-in” for consent in neoliberal frameworks. Despite a myriad of strong reasons for why the mere fact of a signed agreement cannot be evidence of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) as it is understood in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, extraction in the contemporary moment seems to be authorized by this “ruse of consent”, as Audra Simpson calls it. The successful conclusion of a deal provides both crucial legitimation for political actors supporting contested resource projects, and a valued asset for companies seeking to market their projects to potential investors.

In the Ring of Fire, it has become clear that improvements to the desperately-needed community infrastructure, were – until very recently at least – intended to come in exchange for supporting mining, joining the wage economy, for consenting to be ‘included’ and folded into the narrative of progress crafted by outsiders to the region. But Neskantaga keeps pushing back; they assert Anishinaabe sensibilities, practices and ways of knowing at every opportunity. Regulatory exchanges and email threads are punctuated by their insertion of dissonant logics and language. The narrative of their inevitable absorption is interrupted by their refusal, and as Simpson might say, “by their continued life itself”.

Mainstream forecasting predicts exploding demand for a number of metals and ‘critical’ minerals to support technological developments in renewable power and ‘clean tech’ in the coming years. But what is a ‘just transition’ in this context? What does it look like in particular places and for particular peoples? Breaking out of our well-entrenched patterns of colonial and capitalist exploitation must be part of the answer. The UNDRIP’s free prior and informed consent (FPIC) standard is a starting point (and Canada is considering adopting it into Canadian law) – but being granted the right to consent to outsider’s plans is not the same as being given time, space, and resources to develop your own visions for the future of your homelands, in line with your own social, legal and political orders.

There are deep rifts between Indigenous peoples’ legal orders which often rest on principles of deep relationality with lands, waters, and other beings, and extractive logics, in which elements of the earth are understood as resources presumed to exist for the sole purpose of providing sustenance to humans. The idea that humans may be in relationships with these elements, that these elements exist in relation to each other, and that those relations may include not just the right to ‘take’ but obligations to protect or to steward, is emerging as a direct challenge to extractivism.

In thinking through our support of an energy transition, let’s be sure to stimulate a logical transition as well. ‘Refusal’ maybe a way of holding out for that – for rejecting extractivist logic in all its new ‘clean’ guises. For ushering in an actual post-extractive embrace of life-giving, care-taking economies that sustain us in mutual relation.