Jessica Crowe – Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Ruopu Li – Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Proponents describe the American Jobs Plan as an investment in America that will create millions of good quality jobs through rebuilding and enhancing the country’s infrastructure. The plan encompasses several diverse aspects of infrastructure, from traditional forms such as repairing roads and bridges to newer forms including expanding broadband infrastructure to reach all areas. A major component of the plan is to transition from carbon intense technologies and energy sources to greener industries as well as to train Americans for these newer, greener industries. By some estimates, the transition from highly polluting, greenhouse gas intense industries to carbon pollution-free energy would create millions of jobs in the energy sector. Despite solar accounting for only 1.6 percent of the total U.S. electricity generated in 2018, the solar energy industry employed 334,992 people in the United States in 2019—by some accounts more than any other energy industry in the U.S. In addition, solar employment grew 11 percent annually between 2013 and 2018—six times faster than overall U.S. employment. Given the potential for growth, it’s easy to see how transitioning away from carbon-intensive fossil fuels to cleaner, renewable forms of energy can create many jobs while simultaneously moving toward 100 percent carbon-pollution free power as intended by the American Jobs Plan.

Support for renewable energy in the United States is not as controversial as it may be portrayed in some media outlets. In fact, overall support for renewable energy is quite strong in the U.S., with recent polls consistently showing high levels of public support for solar panel farms. While less support generally exists for solar power mandates (such as the one in California for rooftop solar on new home builds), in a recent survey of 1316 Americans, we found that 70% were in favor of a similar mandate for rooftop solar in their own state. The percentage rose for people who agreed that they would like to live in a home that mostly powered by solar energy (78% of respondents) and who agreed that more effort should be made to employ more people in the solar industry (76% of respondents) (Crowe, 2020). Even among residents living in a historical coal-mining county where people were still employed in the coal industry, we found respondents’ overall attitudes about solar energy to be favorable—even more favorable than their overall attitudes about coal (Crowe and Li, 2020).

While polls show perceptions of renewable energy to be favorable, even among those who live in areas occupied by the fossil fuel industry, it is important for a transition to a low carbon society to be just. To have energy justice, a society must apply justice principles to all features of energy consumption and production, including policy and activism. Generally, energy justice has three components: distributional, recognition, and procedural. First, distributional justice evaluates where injustices emerge. Second, recognition justice examines which affected sections of society are ignored or misrepresented. Finally, procedural justice investigates which processes exist for their remediation in order to reveal and reduce such injustice. With respect to recognition justice, injustice can occur when the dominant group fails to recognize a specific group’s (e.g. social, geographical, cultural, ethnic, racial, gender) viewpoints or distorts a group’s views in ways that appear demeaning. Recognition justice is especially important for place-based communities who will endure the most from an energy transition either by losing energy related jobs (e.g. nuclear and fossil fuel) or by hosting the sites for renewable energy (without their input or support).

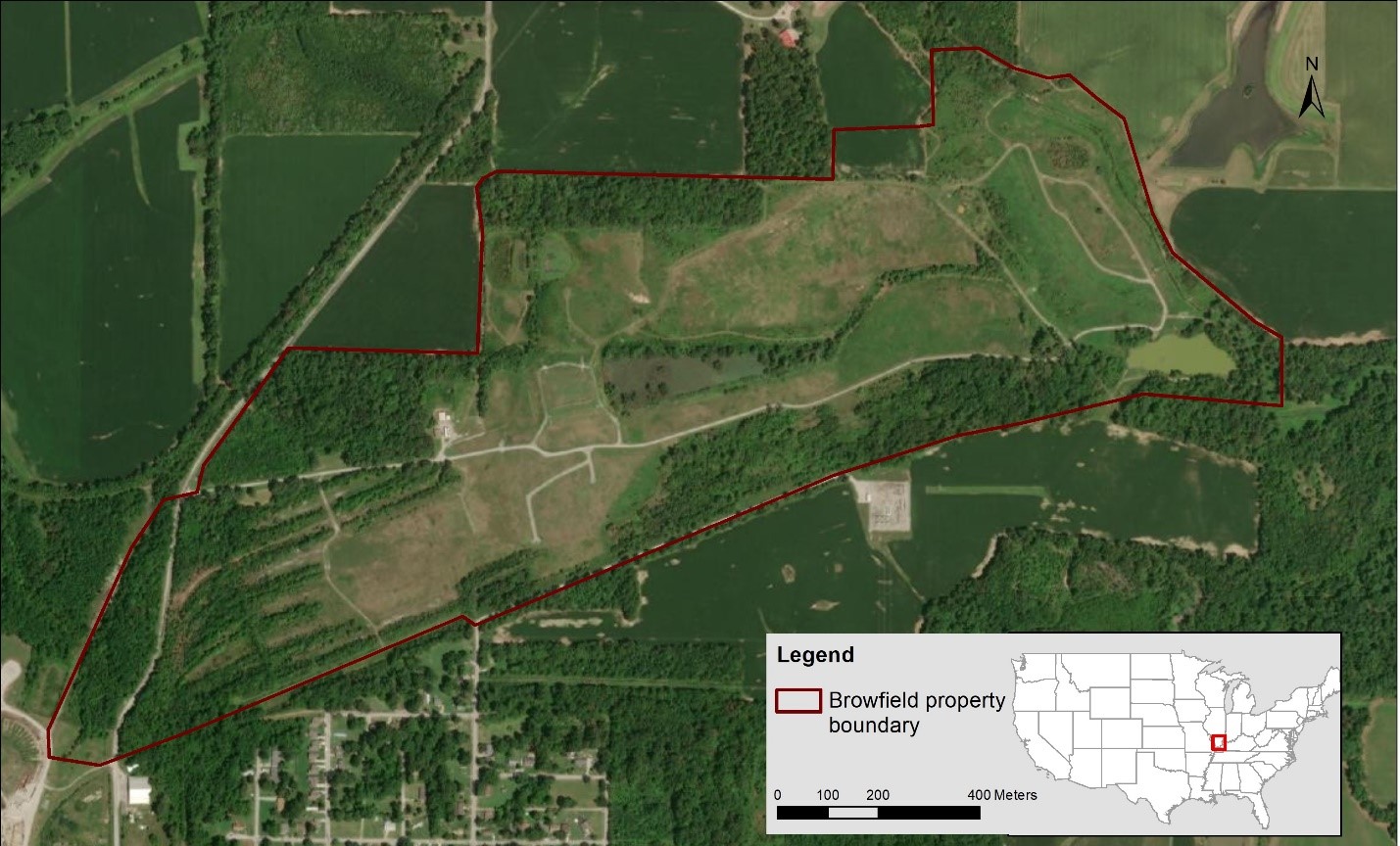

To illustrate an example of recognition (in)justice, we present the case of Brightfields Development LLC and the City of Carbondale, IL. In August of 2013, Brightfields Development applied for a special use permit to develop a solar panel array on the site of a former wood-treating facility located in the northeast side of Carbondale, IL. Figure 1 shows the property location of the brownfield site. Brightfields Development is committed to completing large remediation projects, specifically remediating brownfields (former industrial sites affected by environmental contamination) by constructing solar farms on the once contaminated land. While in operation (1902-1991), the former wood-treating facility treated railroad cross ties, utility poles, and other wood products with chemical preservatives, including creosote, a known carcinogen. The chemicals were released to the environment and sometimes spills occurred, contaminating soil on the site and nearby waterways. In one incident traced to an overflow of a lagoon at the facility, a fish kill occurred in the nearby Big Muddy River due to phenol poisoning. In another incident, two cows grazing on land next to the facility died. An autopsy performed on one of the cows revealed the cow had ingested creosote-containing material contributing to its death. Furthermore, workers at the facility, about half of whom were African American residing within walking distance of the facility, worked in creosote-laced conditions, becoming exposed to the chemical on a regular basis. Many workers and nearby residents claimed to have developed various skin cancers and cancer of the scrotum due to creosote exposure.

After the wood-treating facility closed in 1991, another company purchased the land and facility and the new owner began working with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to clean up the land. They performed periodic sediment and water testing. They also constructed a containment unit on site and creosote laced soil was removed and stored in the containment unit. In addition, parts of the nearby creek where the chemicals entered were re-routed and an underground trench was built to collect the remaining creosote. Other remediation actions performed by the new owner included installation of a surface cover over the former process area and lagoon area and excavation of visually impacted sediments downstream from the channel relocation. These remediation actions were completed by 2010.

Three years after cleanup was completed on the former wood-treating facility site and nearby waterways, Brightfields Development approached the City of Carbondale, IL to construct a solar panel farm on the remediated brownfield. However, despite the remediation actions that had already been performed under the EPA’s supervision, several residents who lived in the nearby neighborhood were not convinced that sufficient testing had been done on the site. Therefore, they did not consider the area safe and wanted additional testing to be done before allowing the solar panel project to begin.

Despite concerns from neighborhood residents, plans by Brightfields Development LLC continued and the City of Carbondale was set to approve or deny Brightfields Development a permit at a city council meeting in October of 2013. At the October 2013 city council meeting, 80 concerned citizens attended, many who requested the council deny or withhold their decision regarding the development project. The city council unanimously voted to defer the project’s approval until at least two community meetings were held with representatives from the current owner of the land, Brightfields Development, Illinois EPA, and Carbondale city leaders present to address residents’ concerns about the proposed solar farm.

Two public meetings were held in July and December of 2014 at a community center in the neighborhood closest to the facility land. At these meetings, the developers were able to present supporting material on their plan to construct the solar farm and residents were able to voice their concerns and receive clarification about the project. The meetings, while providing more information to neighborhood residents, did not alleviate community members’ concerns. Carbondale city council held a meeting in March of 2015 to vote on the Brightfields Development solar farm permit. At the meeting, a community member speaking on behalf of the Concerned Citizens of Carbondale group stated “if you vote ‘yes’ it will clearly mark the end of an era where residents of a neighborhood can have an impact on what changes can be implemented in their neighborhood.” After several other similar statements by community members, one council member spoke out asserting, “I have not yet seen any concrete reason for believing this proposal will create any risk of adverse consequences, and I see clear potential for good to come out of it.” The council voted 5-2 to approve Brightfields Development a permit to construct a solar farm on 73 acres of the former wood-treating facility site.

Although the city granted Brightfields Development a permit, the permit’s approval had conditions and was time sensitive (3 years). In the three years following the approval of the special use permit, Brightfields Development was unable to meet the conditions and start construction. Therefore, in October of 2018, discussion began again between the community and Brightfields Development during the Planning Commission’s public hearing. In November of 2018, the council once again voted to approve or deny a special use permit for the solar farm. However, this time the Council voted 7-0 to deny the permit.

So what drove the city council’s reversal for granting the permit? A clue can be found among the city council’s own rhetoric. While a city council member at the 2015 meeting was dismissive of community members’ concerns, by the 2018 meeting city council members heavily relied on community members’ judgments. As one City Council member stated after the vote, “We haven’t heard a positive thing about the project from the neighborhood, so it was the end of the discussion.” Since the beginning of the proposed project in 2013 up until the permit denial in 2018, several community members continued to actively voice against the proposal. One well-known activist who lived in the neighborhood for over 65 years openly spoke about the effects of the contamination on friends and family in the form of various cancers. His biggest concern was that neighborhood residents never received any help from the city or from the wood-treating plant when people started to get sick.

By the 2018 city council meeting, city leaders had started acknowledging the concerns of community members as legitimate, even though most city officials were in favor of solar energy. As the Planning Commission Chairman stated, “There’s a history to this that goes back many years, so that’s all involved in this.” Part of that history was described by the director of the Racial Justice Coalition of Carbondale who stated, “There hasn’t been good conversation with the northeast community where this will be located and who has the history with that land, and with the site and with the family members who worked there and died there because of the contamination…who have questions about contamination in their own yards that have not be answered to their satisfaction.”

The case of the proposed solar farm on the remediated brownfield site continues to be debated. Several residents of Carbondale were in favor of the solar project and sided with Brightfields Development’s argument that the solar array could be built without harming the environment or disturbing the contamination below the land. However, as residents of the northeast side continued to speak out and oppose the project, city leaders and other community members began to recognize their concerns and felt that they should be supported, thus ultimately denying the permit. The City of Carbondale is an advocate of solar power, has very recently constructed a solar array on city property next to the police station, and is currently having solar panels installed on the rooftops of government buildings, including city hall. However, this case, in which historic environmental contamination intertwines with future renewable energy development, illustrates the need for energy recognition justice. While transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy is necessary to slow the effects of climate change and to improve human health, taking the time to listen, acknowledge, and support community members and their concerns is necessary to build healthy communities. While it may be difficult to do both, the City of Carbondale is showing that it can happen.

References

Crowe, J. (2020) ‘The influence of issue framing on support for solar energy in the United States’, Environmental Sociology 7(1), p54-63.

Crowe, J and Li, R. (2020) ‘Is the just transition socially accepted? Energy history, place, and support for coal and solar in Illinois, Texas, and Vermont.’ Energy Research & Social Science 59 [online]. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214629618313689 (Accessed: 14 April 2021)

US EPA. (2019) ‘Explanation of significant difference for the former Koppers wood-treating facility, Carbondale, Illinois.’ ILD 000819946. [online]. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-10/documents/koppers_explanation_of_significant_difference_final_9-27-19.pdf (Accessed: 14 April 2021)