Débora Swistun – Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda, Universidad Nacional de General San Martín

Autoethnography of environmental suffering

More than a decade ago, Javier Auyero and I wrote Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown, published first in Spanish (2008) and then in English (2009). The book has since taken on a life of its own, which has also been part of my life, as it is about my hometown. Our research focused on the public dimension of the toxic experiences of Flammable residents, the community adjacent to the biggest petrochemical compound of Buenos Aires, renamed that way by the local government after an oil ship explosion in 1984. We analyzed how the many senses and meanings around pollution, toxicity, harm to health and environmental impact given to Flammable by several powerful actors performed as a “labor of confusion” linked to the social production of toxic uncertainty, deceit and denial.

When Javier, my coauthor, interviewed some residents, their responses to him were somehow homogeneous: “All of us will die”, “We are all ill here”, “The companies are killing us”, and “Everything is polluted here”. They reproduced to him the kind of discourse that the media conveyed about Flammable on the TV they watched and the newspapers they read. When I interviewed my neighbors, however, things looked quite different. Doubts, suspicions and denial about pollution and health effects, what the companies did and did not do, and reflections about whether they would be displaced or the companies would be displaced, dominated the conversations.

We were starting to understand the multiple effects of industrial pollution on urban poverty, a dimension that had been marginal in academic studies. We brought to the forefront the importance of the environmental dimension in the everyday lives of the urban poor in the Global South to understand how social domination works in places like my hometown, where petrochemical companies are like “monsters” and at the same time “fathers or mothers” providing health care, potable water, and jobs.

What doctors, media, companies, teachers, scientists say or do not say about pollution has a differential impact on how residents perceive their own health and their surroundings. In 2003, an epidemiological study showed that more than 50% of children had lead in their blood; at that moment the tolerated dose was 10 ugm/dl, now it is half of this. Becoming aware of the toxic surroundings was a difficult process full of sadness, anguish, sorrow, anger, deceit and denial. We named this process as environmental suffering.

So many things happened after the book’s publication in 2008 in Spanish. It was used by lawyers and other experts struggling for environmental justice for Flammable inhabitants. The residents quoted the book in discussions with local authorities and outsiders to show evidence of their experiences of living in danger but also to show that a different past existed in Flammable when elders enjoyed the river and a completely different landscape without industrial pollution. The companies felt offended by the facts and findings about toxicity that we described in the book. Some state officials felt offended too. Employees from communication and public relations departments at the companies said they realized the social and environmental impacts they had on the communities where they operated.

The co-writing and denaturalization of the history of Flammable, and part of my life by extension, carried me to different places, engaging in environmental activism, advising state interventions to improve the quality of life in Flammable, meeting judges and lawyers, teaching environmental humanities at university, working in disaster risk reduction, but also to be scared and threatened several times by different powerful actors and to be uncomfortably heard. When the claims and proposals to improve the life of Flammable residents ended in disappointment and defeat, and frustration took over my soul, I continued fighting in my dreams, and in the dreams we won; that is the marvelous thing about dreams! Latin-American feminist authors, Foucault and decolonial authors such as Mbembe and his concept of Necropolitics helped me to understand that part of the reality of environmental suffering that we did not analyze in the book: the public dimension of my unconscious. The power of pollution assaulted everything, including my dreams.

Activists, experts, and other professionals who are aware of the multidimensional impacts of our fossil fuel-dependent modern way of living, think of Flammable as a challenge to be solved, as a place to be “remediated”, “relocated.” Some others do not care really; some others deny it; and still others do not have a clue about what could be a solution. I designed and developed interventions to reduce environmental suffering in Flammable while working for the Ministry of Environment in Argentina. It was an extremely important experience for me to be familiar with how politics is designed from the inside, but it was also highly frustrating because most of the solutions we planned for Flammable were dependent on the politics of energy, mainly defined by multinational companies such as Shell. I decided to leave the country with a scholarship for a Master’s in Germany and France but, in my dreams, Flammable appeared again and again.

When I returned to Argentina, my hometown was again in the spotlight because there was a new plan to improve Flammable residents’ quality of life, a relocation from two blocks to make more space for logistic companies. The ombudsman asked me for an opinion about that project. Even though the Supreme Court of Justice had ruled it necessary to improve the quality of life of Flammable residents in 2008, it had been quite difficult to guarantee this. I communicated the plan to some residents and we started advocacy work together again. Nowadays there is an NGO working with the residents seeking to access justice.

Ten years since the Supreme Court of Justice ruling, I still have a question in my mind without a definite answer: why don’t Flammable residents’ lives matter as much as yours?

The concept of environmental racism, the sacrifice zones, a term explaining the “unwanted and unavoidable” impacts of modernization and the capitalist system, and the different sets of values of nature and humanity that powerful actors apply to Flammable offer insights for understanding why these bodies and places are seen as discharged ones. For years, I searched and searched, and I discovered interstitial spaces where the Capitalocene has not corrupted the set of values which tries to give the same importance to all kinds of lives. I met indigenous leaders, people practicing permaculture and low-impact ways of existence, and lawyers doing advocacy work with affected communities. I met great people in those interstices, that nowadays are planetary movements, people who are questioning the effects of the modern way of living and trying to develop new ones, people thinking about how to reverse the historical legacy of the ideology of progress, internalizing the externalities. That line of inquiry carried me to the Aerocene community, who sought me out on the basis of my activism/research. After some brainstorming meetings, we started different collaborative “artivist” (a portmanteau of art and activism) activities in Flammable.

Aerocenic artivism in Flammable

Aerocene is an interdisciplinary artistic effort that seeks to generate new modes of sensitivity, reactivating a common imagination to achieve an ethical collaboration with the atmosphere and the environment. Its artivism is manifested in the testing and the circulation of lighter-than-air sculptures that float powered by the heat of the Sun and the infrared radiation of the Earth’s surface, provoking us to think about other forms of human mobility that are not dependent on fossil fuels and therefore are non-polluting.

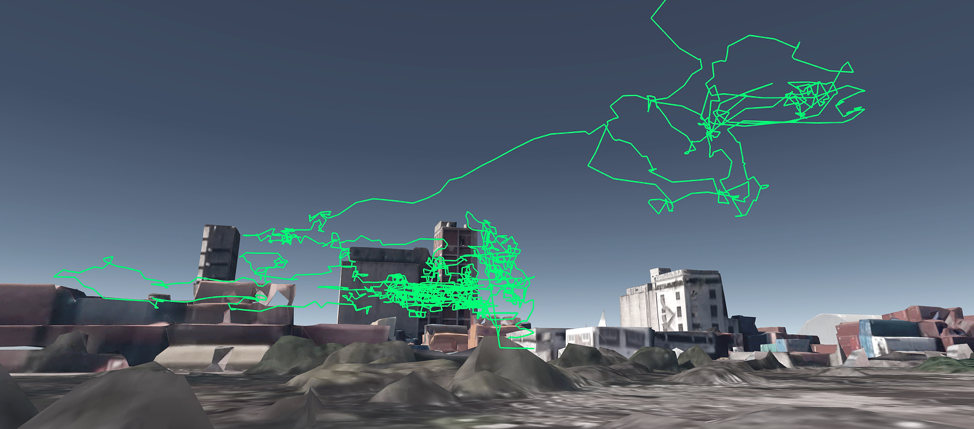

In the tenth anniversary of the Supreme Court of Justice ruling, we flew two Aerocene Explorers to the oil refineries along with the inhabitants of Flammable, and in an act to subvert the persistent environmental injustice in this portion of the planet, we signed in, of and with the air, to end dependence on fossil fuels. The balloons registered atmospheric variables and an Aeroglyph, or signature in the air (see cover image). These signatures that describe the flight of the aerosolar balloons are collected around the world, as signatures in pursuit of an ethical commitment to the atmosphere, for a future free of fossil fuels.

Health treatments, compensations, resettlement of those families that wish to leave the compound, relocation of some industrial facilities, the remediation of poisoned soil, reduction and public control of air pollution and a contingency plan to respond to technological risks would make a concrete difference in the everyday lives of Flammable residents. A possible future of environmental justice for Flammable would have to include all that restitution but also a new era would have to emerge. Rephrasing the Living Aerocene Manifesto: moving towards a fourth metabolic regime would imply developing a new set of values, overcoming the extractive economy of the fossil fuel regime, and forming a new stratigraphy of the post-Anthropocene future. It may be through a rearticulation of our relationship with the Sun, the air, the other natural elements and the cosmos, that we open the limits of our current way of existence on the Earth to new sensitivities, for us and for the others to come.

- Cover image: Aeroglyph by Joaquin Ezcurra – Aerocene Foundation. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.

- Some reflections contained in this text were shared in the art exhibition “On Air” by Tomás Saraceno at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, October 2018.

- Débora Swistun is an Argentine anthropologist. She has specialized in the right to the city and environmental justice, technological risks and co-production of public policies in Europe and the Americas. Her book Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown (with Javier Auyero, OUP; 2009) reveals and analyzes the life experience of her hometown next to the petrochemical compound of Dock Sud (Buenos Aires) and has received four international awards. She is interested in the potential of scientific complementarity with other forms of knowledge to address Anthropocene-related problems, teaches Environmental Humanities (UNDAV/UNSAM) and participates in community, private and governmental initiatives on citizen science, human displacement, disaster prevention and low-impact living. [email protected]