Gwen Ottinger – Drexel University

Shannon Dosemagen – Shuttleworth Foundation Fellow and Open Environmental Data Project

Back in 1995, buckets were a game-changer. The low-cost, easy-to-use air samplers were first developed for a community in Northern California, where the adjacent oil refinery had had a series of toxic air releases. For the first time ever, the bucket enabled refinery neighbors to find out what was in the air.

Communities across the United States and around the world soon adopted the bucket. They took air samples in response to noxious odors from neighboring refineries and petrochemical plants. They used bucket results to contradict industry’s claims that their operations were harmless to residential neighbors. They used buckets to shame regulatory agencies into conducting more of their own monitoring. Throughout the late 1990s and first decade of the 2000s, buckets contributed to important environmental justice victories.

But are buckets still relevant in 2020? A new crop of continuous air monitors has made it possible for communities to get more air quality information at a lower cost. Regulatory agencies are beginning to require monitoring at refinery fencelines, at least in the U.S. There is momentum worldwide around citizen and community science, and regulatory agencies are becoming more open to community participation in environmental monitoring.

At the same time, some of the organizations that helped launch the bucket are questioning the vaIue of monitoring. They’re fighting to stop massive new petrochemical plants, demanding hard upper limits on petrochemical emissions, and championing a transition away from fossil fuels entirely. Bucket monitoring would serve these ends indirectly, if at all.

Buckets are no longer the only tool available to data-hungry communities, and they aren’t the most powerful tool for every campaign. Yet we contend they still deserve a place among the resources available to frontline communities. Technically, they surpass low-cost and continuous monitors in their ability to measure numerous toxic air contaminants at very low levels. For the community who wants to capture benzene, toluene, dichloroethane, and hydrogen sulfide, buckets remain the best choice. Buckets are also uniquely hands-on and community-oriented. Neighbors work together to build them and organize around sampling–interactions that off-the-shelf monitors don’t promote.

With the dissolution of Global Community Monitor (GCM) in 2016 and the passing of its founder, Denny Larson, in 2019, the bucket lost powerful allies. Helping frontline communities integrate bucket monitoring into their campaigns had been Denny’s life’s work. We worried that communities who could benefit greatly from buckets would have nowhere to turn in his absence, especially as expanding resources for citizen science may make buckets seem obsolete.

Our team has spent the last nine months collecting, creating, and curating resources for bucket users and frontline communities who wonder how buckets might be able to help them. These resources are housed on the Public Lab website, where anyone can chime in with their questions, experiences, and tips for other users. Here’s some of what you can find there:

The Bucket Build

The first buckets, built by a private engineering firm and distributed to residents of Rodeo and Crockett, California, didn’t come with blueprints. Staff and interns at Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) reverse-engineered them, created parts lists, and wrote instructions for how to build them, so that buckets could spread to other communities. The result was the original Bucket Brigade Manual, which we’ve reposted with permission.

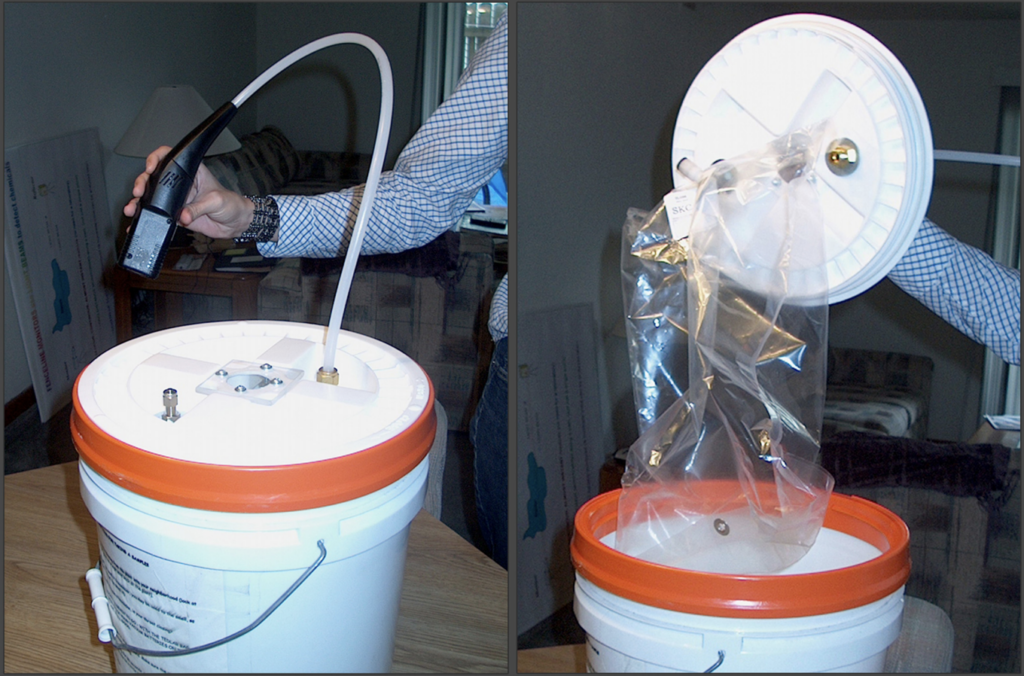

A lot has changed since the first bucket manual–and even since subsequent versions created by GCM in 2002 and 2006. The bucket’s design has been updated, thanks to the innovations of communities around the world. Vendors have changed, too. And the technologies we have for sharing information are very different from what CBE had to work with in the mid-1990s.

Taking all of that into account, Community Technology Fellow Katie Gradowski has developed updated guidance for how to build your own bucket. She’s posted an illustrated how-to, videos of a build in progress, and resources collected by community groups who have used the bucket successfully for over twenty years. To make it even easier, Public Lab will start offering a bucket kit in 2021: all of the parts you need for a bucket in one package.

Bucket Craft

Over time, it became clear that how to build and use a bucket wasn’t something most people would learn by picking up a manual. There was a craft to building a bucket, to knowing when to take a sample, to knowing how to use sampling results to maximum effect. Communities learned the craft of sampling from organizers and other communities. They figured out how to leverage results to spur systemic change, closing toxic facilities and getting regulators to step up. Then they added their own experience to the collective knowledge.

The South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA) and groundWork South Africa have two decades of experience in the craft of using buckets. They’re working with us to make their knowledge widely accessible, in a series of short how-to videos and interviews. They show us how to take a sample, including how to pick a spot and how to fill out a chain of custody form. They also show us around the neighborhoods where buckets have become part of the fabric of organizing over the years, and they explain how they’ve turned bucket sampling into real, positive change, including the passage of South Africa’s Air Quality Act in 2004.

Knowing how to interpret and use bucket results is an especially tricky part of the craft. Here we feature insights from SDCEA and groundWork. We are also fortunate to be able to share guides developed by TERC and GCM, on such topics as holding a meeting to discuss results and keeping a pollution log. In addition, Katie has also compiled a list of guides developed by a variety of community organizations. These are a treasure trove of advice on the craft of air monitoring for environmental action.

For any craft, it’s helpful to talk to practitioners in real time. We’re starting this process by featuring the bucket in Public Lab’s OpenHour call on Wednesday, December 9 at 12:00 pm EST (UTC-5). Facilitators include Rico Euripidou, Environmental Health Campaigner at groundWork; Katie Gradowski, Public Lab Community Technology Fellow; Bongani Mthembu, SDCEA; and Desmond D’Sa, 2014 Goldman Prize Recipient and Co-Founder of SDCEA. If you’re interested in how buckets can help your community, we encourage you to join. (Details on how here). If you miss it, you’ll find video of the session posted afterwards on the OpenHour page.

Bucket Successes

We take inspiration from what communities have been able to achieve by integrating bucket monitoring into their organizing. The resource collection highlights success stories, including how residents of Tonawanda, New York, used bucket samples to hold Tonawanda Coke accountable for dangerous levels of benzene in the air. In South Africa, bucket monitoring by SDCEA and groundWork contributed to the development of the nation’s Air Quality Act in 2005.

We’d love to grow the collection of bucket success stories. If you have one to share, please let us know–or add it directly to the editable PublicLab.org website.

An On-going Project

The success of buckets has always depended on the dedication of many people, and it takes on-going involvement to keep evolving the strategies that make buckets effective. We hope you’ll join us in keeping up this tradition. If you’ve never used a bucket but toxic air contaminants are a concern for your community, check out the resources we’ve compiled. Post your questions. Tell us about what worked for you and what didn’t. If you have been using buckets, please share your story, or respond to other community members’ questions. We hope that, using the technology that’s now available, we can together become a thriving community of bucket users and allies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the 11th Hour Project, a program of the Schmidt Family Foundation, for their generous financial support of this project. For sharing their knowledge of the bucket’s history, use, and impact with us, we are grateful to Azibuike Akaba, Ruth Breech, Jackie James Creedon, Desmond D’Sa, Rico Euripidou, Bongani Mthembu, Bobby Peek, Anne Rolfes, and the Statistics Action Team at TERC. We thank Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) for permission to republish the original bucket manual. Finally, we very much appreciate the efforts of Katie Gradowski, Annie Schillo, and Public Lab staff, all of whom helped bring this project to fruition.

Cover image: Gwen Ottinger, Public Lab.