Sam Mason – Public and Commercial Services Union

The Coronavirus pandemic has thrust science and technology into the spotlight with urgent and necessary priority. In parallel, assumptions about the nature of work and what skills are valuable in society and the economy have been challenged as health and social care workers, along with many low paid ‘invisible’ workers in retail, transport, local and central government authorities have been brought to the fore. In the background, however, there remains the climate crisis and questions about the future of work, which the response to a global public health crisis is laying the foundations for in the interests of capital.

A vaccine may eventually save humanity from a deadly virus, but we cannot vaccinate ourselves against our own human destruction through ideological-techno fixes. Solutions that embody neoliberal market-based policies, negative emissions technology, and working practices that decommission workers rather than harmful fossil fuel infrastructures including the power structures that support them.

As the principles of Just Transition have become mainstream, its value to the working class has become extracted to suit capital’s rather than workers’ needs. Yes, the sudden halt to ‘business as usual’ has shown how we can call a break on the multiple crises of inequality, climate change and increasing automation in a way that doesn’t just react to these threats but rather one that proposes alternative workers’ solutions. The root of this is understanding our past to transform our future.

Long waves of de-industrialisation

The industrial revolution created the conditions of the working class which laid the foundations of organised labour. Through periods of ‘long waves’ of industrialisation (Lloyd-Jones, 1990), the benefits from this have risen and fallen linked to wider political economy objectives of the day. In developed nations at least, they have generally seen rises in living standards but the neoliberal economics of the past decades have seen major changes to work with rising inequalities between and within nations.

Whilst much has been referenced in UK industrial development to the coal industry, and later North Sea oil and gas, it is an oversight to forget the development of wider productive processes linked to an ‘accumulation by extraction’ – mineral, hydrocarbon or human. Whilst extractivism can be understood in terms of abuse of the environment and often people in the process, particularly indigenous peoples, there is a link also to the robotisation of work, and the extraction of workers’ knowledge and skills into the very machines and systems we use or make. This concept is exemplified in the mass production and assembly lines developed by Henry Ford at the turn of the 20th century. Whilst Ford recognised that he needed to keep a workforce well paid in order to buy the fruits of their labour, it was ultimately monotonous and deskilling work. The subsequent introduction of practices such as Taylor’s scientific management or lean working in production processes have transferred into what can be called the industrialisation of white collar jobs (Kämpf, 2018).

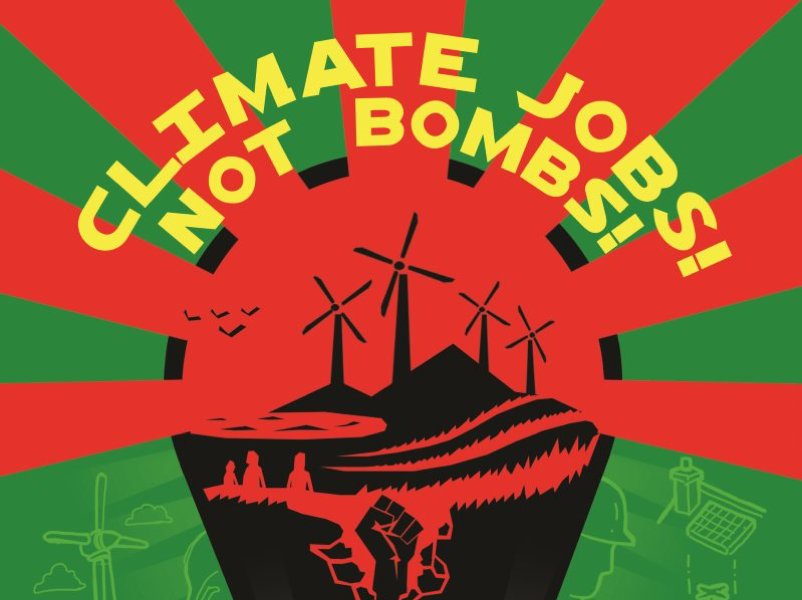

This embodiment of human knowledge and skills within technology was well understood by the former Lucas Aerospace shop stewards when fighting redundancies in the 1970s. These workers were pioneering in developing what the Financial Times referred to as one of the most radical workers’ plan in history. In developing an alternative plan for socially useful production, they emphasised producing things that society needed over the profit motive, workers as part of a community, and ensuring a human-centred labour process. In short, understanding technology as political.

Image 1. Lucas Aerospace Show stewards (source: The Guardian).

It is no coincidence that greenhouse gas emissions have increased as extractivist projects and production techniques have become more capital rather than labour intensive. Alongside which we are seeing shifts in labour market patterns that go beyond deindustralisation to service-based work. The ILO world of work report showed that the informalisation of work traditionally associated with the Global South is now becoming a globally prevalent model. Based on zero hour and precarious contracts, loss of control over working time and on-demand working, such as in the fast food sector, it is creating what some of have called a new precariat class.

Of course, not all technology is bad. What changes the dynamic is knowing in whose interest it is utilised, by whom, and what level of workers’ control and autonomy it enables. A point that was borne out in a report by Public Services International looking at digitalisation and public services emphasising the ceding of power to global tech corporations. If fossil fuel inputs were the driver of the Industrial Revolution, data and knowledge management is the driver of the so called 4th Industrial Revolution.

These corporations are wielding ever increasing control over our lives in ways which are not always obvious. For example, they are set to be key players in the delivery of new energy services in the drive to smart energy use. A correlation between smart technology, jobs and energy inputs that is little discussed in the wider debates around energy transition and work. Nor the so called high skilled jobs in energy in the Global North, compared to the exploited workers in extractive energy economy in the Global South.

Reclaiming a working class just and transformative transition

The Just Transition concept dates back decades to the US labour movement and trade unionist Tony Mazzocchi, who recognised the need to challenge the link between work and the environment. He saw clearly how workers were exploited in the same way nature was in the jobs they did to serve capitalism. Whilst it was only in 2015 that these two words finally made it into the preamble of the Paris climate agreement, it is now the lingua franca of climate talks, NGOs, and even Richard Branson.

This co-option of the language shows a failure of the labour movement to articulate a bold vision around Just Transition based on working class power challenging the capitalist framework. Rightly drawing criticism from the Global South for prioritising a northern development model, it also fails to address issues of political economy which should be at the heart of informing a labour, and when needed militant, response.

Some trade unions, largely on the public sector side, argue that we need a transformative transition that challenges the inherent inequality of the capitalist system. This idea embodies a whole economy approach that goes beyond the energy sector and unions within it, which have sought to dominate the Just Transition agenda to the exclusion of large numbers of the workforce, including unorganised labour. It also fails to acknowledge the parallel processes of the increasing automation and digitalisation of work. This is happening in the North Sea, where unions support the ‘maximising of economic resources’ (MER) to extract every last drop, to the aviation sector. Two sectors decimated by the Coronavirus pandemic and which are currently in the process of a transition that is very far from just.

Alongside this, we also have a range of techno-fixes in terms of negative emissions technology that are sold as decarbonisation solutions. These include Carbon Capture Use and Storage (CCUS), and blue (natural gas) hydrogen. Policy proposals that are also supported by trade unions as ways of ensuring new jobs for their members that will require little transition, in the sense that the workers will just need some retraining or repurposing of their roles. A view that seeks to perpetuate ‘business as usual’ without the emissions.

It is the duty of all trade unions to fight for the protection of their members’ jobs. But this cannot be done at any cost. Not at a cost to the environment, to our international solidarity with others on the frontline of climate change in the Global South, to the exploited workers in global supply chains, or to workers outside of organised labour. Our thinking needs to go beyond our institutionalised industrial structures.

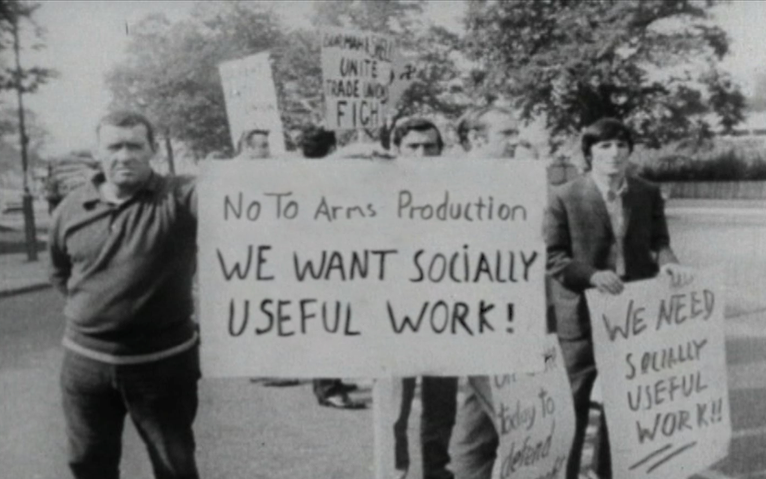

Image 2. Campaign against climate change – Trade Union Group (source: the author).

Rather we can fight for jobs by arguing for alternative policies based on economic, social and environmental justice. The rise of support for a Green New Deal embodies this idea but for many it does not go far enough, as it fails to really tackle the structures of power. Other initiatives, such as the Global Trade Unions for Energy Democracy, put power and ownership at the heart of their proposal. It argues that we need to reclaim our energy system, resist the power of the fossil fuel corporations, and restructure it as a public good. Further, it recognises the weakness in social dialogue structures for labour and advances a more collective position of building social power.

COVID-19 convulsion

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown how we can make a rapid transformation needed to tackle the climate crisis. National governments are funding unprecedented levels of stimulus packages to underwrite the economy, including for workers, cities are enjoying cleaner air for the first time in decades, and global emissions have fallen. But there is no guarantee these will remain as capital seeks to reinvent its business model, discarding ‘old’ technology being rapidly brought in under the ‘emergency’ guise with relaxation of the already weak regulations that do exist.

There has been a drive for changes in the ways of work, such as working from home. These are welcome in many cases to help with more flexible notions of working practices. As for many the experience of working from home will gain more favour to this transition, there will be wider impacts on communications and travel and the jobs we do. This may have environmental benefits if it enables us to reduce pollution in our cities, but this leap made on the back of a crisis without industrial and political scrutiny merely ensures capital’s determined path to the so called 4th Industrial Revolution.

If the Coronavirus pandemic has given us a glimpse into our future, it is certainly not a welcoming one. We are at a critical juncture. If we fail to take a wider political and social view to end the extraction of workers’ skills and knowledge to be reengineered into machines and processes, we are reducing workers to arguing for their own extinction.

Or this could be our great, last chance, the opportunity to create the zero-carbon world we need on our terms. An industrial revolution for a society and economy based on a workers’ transformative industrial plan for socially and ecologically useful work, that harnesses technology for social power.

References

Kämpf, T. (2018). Lean and White-Collar Work: Towards New Forms of Industrialisation of Knowledge Work and Office Jobs? TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 16(2): 901-918. DOI: 10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1048.

Lloyd-Jones, R. (1990). The First Kondratieff: The Long Wave and the British Industrial Revolution. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 20(4): 581-605. DOI:10.2307/204000

Header image source: Socialist Appeal