Linda Soneryd – Department of Sociology and Work Science, University of Gothenburg

In a pandemic situation, defined by the World Health Organization, WHO, as ‘the worldwide spread of a new disease’, we all need to listen to experts to know how to act for the safety of ourselves and others. Since it is a new disease with worldwide reach, the challenges we face transgress the usual boundaries set up between administrative units, political mandates, and areas of life. Experts are specialised and employed for specific tasks. One problem with expert advice in complex situations is that the expertise is bounded while the problems are not.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a diverse set of regulatory measures such as national quarantines, the closing down of schools, museums, and hair dressers, bans on events and gatherings, restrictions on the size of groups that can meet and at what distance from each other, mandated face coverings, banned visits to elderly homes, recommendations to work from home, and instructions on how to wash your hands and for how long.

The regulatory measures have varied from being mandatory to non-mandatory, from targeting business or public institutions, to citizens and the general public. During the spring this year we could see the world changing, step by step: national borders were closing down and travelling between countries was made more and more difficult. The strategies and measures within countries differed substantially. Many European cities soon became ghost towns, because of national quarantines or because all shops and public institutions closed down, and social distancing was recommended, while others seemed to remain more or less the same as before the COVID-19 outbreak. The regulatory measures, or lack thereof, have been heavily debated and criticised – either for being too restrictive, impinging on individuals’ and societies’ possibilities to make a living and threatening fundamental democratic values; – or for being too loose, or non-existing, and therefore causing unnecessary deaths and suffering, directly caused by COVID-19, or indirectly because of constrained health care systems.

Image 1. Cafe in Stockholm, Sweden (source: Photopin.com).

Regulation is productive, it transforms relations, shapes identities and distributes responsibilities (Lidskog, Soneryd & Uggla, 2009). Regulation can be understood as risk management, the overarching goal not being to eradicate risk but to make uncertainty manageable by drawing boundaries for what is acceptable and developing systems for controlling risk. The regulatory measures are thus always produced in conjunction with the making of a range of other things: what are the threats? who or what needs to be protected? who needs to act? It is in this context – of valuations, prioritizations and redistributions – that expert advice is situated. To highlight the co-productive features of regulation is not about underestimating the problems that need to be managed. The COVID-19 pandemic is related to real problems such as deaths and economic recession, and already vulnerable groups of people are being affected the most. On the contrary, analysing how regulation is co-produced with the problems it is supposed to manage, will help us understand the problems and manage them better (Jasanoff, 2013).

Social problems, expertise, and relevance

How an event or situation will result in a certain understanding of a problem is never given. It is even less evident which situations will gain attention and become acted upon by governments (Benamouzig, 2014). In public debate, the COVID-19 crisis has sometimes been argued to prepare us for the transition that is needed because of climate change. But in relation to climate change we don’t see the same reaction. There is now talk about a climate crisis but this shift in terminology is not enough in order to create a sense of urgency and an immediate call for action. The number of deaths is not enough either to create attention around a problem – according to the WHO, 7 million people die each year because of air pollution – but this fact has not led to the immediate closing down of coal power stations or bans on car traffic. Environmental activists have known this for a long time. It is often easier to create attention around something that can be localised to a single event – like an oil spill – rather than something that is an effect of many slow processes.

The COVID-19 crisis is an example of how a situation is judged as unacceptable and in need of action, and special measures by governments around the world. Defining a problem is never neutral. Which actors that dominate the debate will affect what problems that are given attention, and thereby which people and living conditions that the problem description is mirroring. When issues are framed as health risks, they are at the same time framed as issues for a limited number of experts to manage. This can be seen also in the debate around COVID-19, experts that are cited are typically virologists, immunologists, epidemiologists, but also sociologists and statistics.

Expert advice and popularised science

COVID-19 is to a large extent framed as an expert issue, and therefore imbued with expectations for a correct way to act, according to available expertise. In current societies there are strong ideas about the relation between knowledge and action, if we have the knowledge we also know how to act. But knowledge does not automatically guide action. There might also be a mismatch between the problem that guided the knowledge production, and the problem seen by those who are supposed to act on the basis of this knowledge.

One example of this can be seen in the Swedish Food Agency and their recommendations aiming to guide consumers to make conscious choices concerning healthy and safe food. A recent analysis of the Swedish Food Agency asks how its advice functions as science communication and what relation between “science” and “the public” it is based on (Gunnarsson 2019).

The recommendations formulated by the Swedish Food Agency are based on compilations of the latest research. The relation between food and health is complex, controversial and difficult to research. Nonetheless, the recommendations need to be formulated in a way that makes them easily accessible to non-experts. The mainstream idea of popular science is grounded in a view of a linear process in which knowledge is first, produced, reviewed and interpreted, and then, it is popularised and communicated to a wider audience in a simplified form. However, popularised science enforces a particular relation between scientific experts and publics: non-experts are left with simplified versions of science and do not get access to the “real science”. It means that a strong privilege of interpretation is granted to scientific experts.

The practice of translating epidemiological and statistical data on public health and food habits to advice for individual citizens, creates a situation where the contradictions, uncertainties and differences between individual beings disappear in the popularised advice. This opens up for a critique that can reintroduce the uncertainties and undermine the whole logic behind the popularisation.

Similarly, the advice given by expert agencies in the COVID-19 situation is typically based on data and recommendations at a population level, and is usually not diversified in relation to differences between individuals or groups. When some specific recommendations are directed to certain vulnerable groups, these are typically based on broad categories and not grounded in the specific knowledge and experiences of people belonging to these heterogenous groups.

Expert advice as distribution of responsibilities

Expert advice will not only involve a narrowing down of the problem, it will also always include assumptions about who is expected to act and with what resources. Expert advice thus also involves a distribution of responsibilities. Sometimes the advice is directed to health care and home care settings and thus target organisations and professional groups, for example WHO:s recommendation on the rational use of personal protective equipment. In order to comply with recommendations, there seem to be several organizational dimensions, resources in terms of staff, equipment, and administrative routines that are required, i.e. aspects that might not be in place for all organisations and available to all professional groups that are expected to be guided by the advice.

Image 2. Protect yourself and others from infection (source: Public Health Agency of Sweden).

In a similar way, the recommendations formulated by national agencies directed to the wider public are based on assumptions about what people can and should do. However, if the goal is to reach out to all groups in society, including particularly vulnerable groups, such as drug addicts and homeless people or groups that may be hard to reach, such as religious and ethnic minorities, experts might need to nuance their advice. In order to choose regulatory measures that organisations, professionals and individuals are all expected to contribute to, including the resources needed in order to comply with them, experts might need to work in close collaboration with the concerned groups that can help to provide contextual knowledge generated outside of formal scientific institutions (for a discussion about the role of social science as expertise, see Citizen Social Science on Covid-19).

Expert advice and its legitimacy

Expertise – if it is to be useful, needs to be perceived as legitimate. It is only legitimate if it responds to peoples’ wishes and problems. Who is allowed to speak about what is desirable, and what is problematic and for whom, is therefore crucial. The COVID-19 strategy in Sweden, based on self-regulation, has been very controversial but it has also been explained in terms of trust (The Guardian, 20 April, 2020).

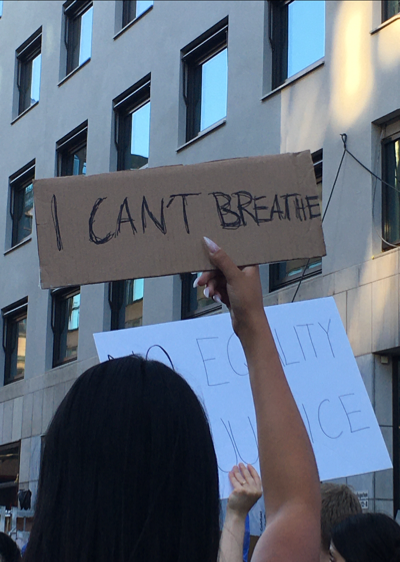

Stricter measures of national quarantines and the bans on larger gatherings on the other hand have been met with worries that these measures are threatening fundamental democratic values. So, is it possible to combine open societies with responsible actions in relation to a pandemic? A demonstration in support of black lives, after the death of George Floyd, was given permission by the Police in Stockholm early June, 2020. The permission only allowed 50 people to gather but far more turned up. Many demonstrators wore a facial mask, to avoid the spread of the virus.

Image 3. Demonstrator in support of black lives, wearing a facial mask (foto: Mirjam Kjellman).

As Sheila Jasanoff has pointed out, there are not only science advisors, there is also a science of science advisors. Science and technology studies (STS) have had a particular focus on how problems are framed in ways that make certain knowledge and expertise relevant and other aspects less relevant or even ignored. While STS expertise has sometimes been employed for instrumental reasons, and not least in relation to emerging technologies, it could also be used for normative as well as interpretative reasons.

Trust is relational and built up over time, and is dependent on how well experts and decisionmakers have succeeded to attend to and respond to the needs and problems that concerned groups have mobilised around. It may very well be possible to combine an open society and collective efforts to avoid the spread of a pandemic. We need regulations that protect people’s lives and democratic values. If the right for citizens to mobilise around issues that concerns them is limited, we have also limited the possibility to guard the expert advisors (Jasanoff, 2013). STS can be an interpretative resource and show how problems transgress and make visible the ways societies are ordered, and a normative resource and engage in how relevant expertise and peoples’ concerns are intrinsically intertwined.

References

Benamouzig, D., Borraz, O., Jouzel, J., & Salomon, D. (2014). A sociological checklist for assessing environmental health risk. European Journal of Risk Regulation 5(1), 36–45. DOI: 10.1017/S1867299X00002932

Gunnarsson, A. (2019). Kostråd som populärvetenskap. In L. Soneryd & G. Sundqvist, Vetenskapligt medborgarskap (pp. 45-65), Lund: Studentlitteratur. (Eng. “Food advice as popular science”, in Scientific Citizenship)

Jasanoff, S. (2013). The Science of Science Advice. In R. Doubleday & J. Wilsdon, Future Directions for Scientific Advice in Whitehall (pp. 62-68). Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

Lidskog, R., Soneryd, L., & Uggla, Y. (2009). Transboundary Risk Governance. London: Earthscan.

Header image source: BBC.