Patricio Flores Silva – Department of Sociology, University of Warwick

In his famous book 1984, George Orwell describes a dystopian society, a society where people are strictly controlled in every detail of their daily life. In Airstrip One, where the main character of the novel lives, it is not possible to think beyond the limits imposed by the newspeak, whose observance is carefully patrolled by the thought police. And if someone tried to go against the established limits, there was a place waiting for him/her: the room 101, where rebels would learn to love the Big Brother.

At least for now, we do not need to read 1984 to know what it means to live in a dystopian world. Most likely, 2020 will be remembered as the year when a large part of humankind did not have an option other than remaining confined at home for entire weeks, avoiding any contact with people from outside and trying to observe hygiene habits compulsively. “Stay at home”, “sneeze on your elbow”, “wash your hands”, “wear face masks”, among other slogans, are the new rules that govern our daily life today.

However, in parallel, nature shows signs of relative recovery. In many places around the world, the air is cleaner than ever, water streams look healthier and carbon emissions have significantly dropped. Even wild animals seem to feel safer, taking advantage of our confinement to explore our cities. In the middle of a human catastrophe, life finds a way, although, for our misfortune, it is not the kind of life we commonly prioritise.

Image 1. Cougar roaming in Santiago of Chile during the lockdown (source: The Telegraph).

Through these contradictory trends, the COVID-19 crisis makes evident the deep connections between human development and the current environmental crisis, an environmental crisis instigated by the conceptualisation of the environment as a mere natural resource, an asset which is there just to be exploited by us according to our own interests. Following this logic, we drill the earth to extract valuable minerals, we destroy wild areas to enlarge our cities, or we take species from their habitats to exchange them like any other commodity, generating in the process all sorts of problems, like “megadroughts”, massive forest fires, or, as it is currently happening, zoonotic diseases that we cannot control.

While many countries continue to be deeply affected by the Coronavirus, others start to show signs of relative recovery. In this context, some sectors try to impose a newspeak where environmental concerns do not have space; now, they say to us, is the moment of economic recovery. However, we cannot go through this crisis without reflecting on the many problems it reveals about our relationship with the environment and our way of dealing with environmental risks.

This issue of Toxic News seeks to offer some analytical keys to think about these problems. Firstly, Linda Soneryd invites us to reflect on the role played by experts in the context of the pandemic, highlighting their limits in the face of a virus that challenges our epistemic or disciplinary frontiers. Her reflections resonate beyond the current health crisis, leading us to think how, in their attempts to deal with the risks derived from transnational crises such as global warming, experts end up turning into part of the problem they are called to solve.

Similarly, Abby Kinchy and Dan Walls analyse the COVID-19 outbreak in the US and the strategies defined by regulatory institutions to deal with it. Based on their research about lead in urban soils, they establish an interesting parallel between the responses offered by public agencies to the pandemic and those commonly followed by them to deal with more familiar threats, stressing how these strategies result in an uneven distribution of risks among the population.

Thirdly, Sam Mason reflects on the opportunities derived from the current juncture to think about a new deal between economy, workers, and nature. In particular, Mason problematises the notion of Just Transition, emphasising how it has lost its transformative potential to suit capital’s interests. Yes -she argues-, we need a transition, but it needs to be thought out from a broad perspective, taking into account both workers and the environment’s needs.

Subsequently, Ekaterina Gladkova addresses the challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis for our current food production systems. Based on the case of industrial farming, she reviews the links between meat production and procedural injustice, emphasising how the ethos of economic growth leads to the exclusion of people’s concerns in favour of industrial farms that, besides causing massive pollution, generate the required conditions for the proliferation of infectious diseases. This last point is also discussed by Nickie Charles, who analyses the problem of industrial farming and zoonotic diseases in light of our relationship as a society with animals and the environment.

Finally, María Cristina Fragkou analyses the neoliberal policies applied in Chile to manage water resources and the obstacles derived from them to control the pandemic in the country. In particular, her contribution sheds light on how these policies, in giving priority to corporate interests, configure a scenario where water flows unevenly through the population, leaving rural communities and informal settlements highly exposed to health-risks like the Coronavirus.

As some countries around the world start to ease their lockdown rules, many authorities invite people to live their lives under a “new normal”. And yes, we need a new normal, but this new normal must be defined democratically, involving groups normally excluded from decision-making, and, especially, keeping in mind nature and other ways of life affected by human activities. We hope the articles gathered in this issue will help to pave a way to progress in that direction.

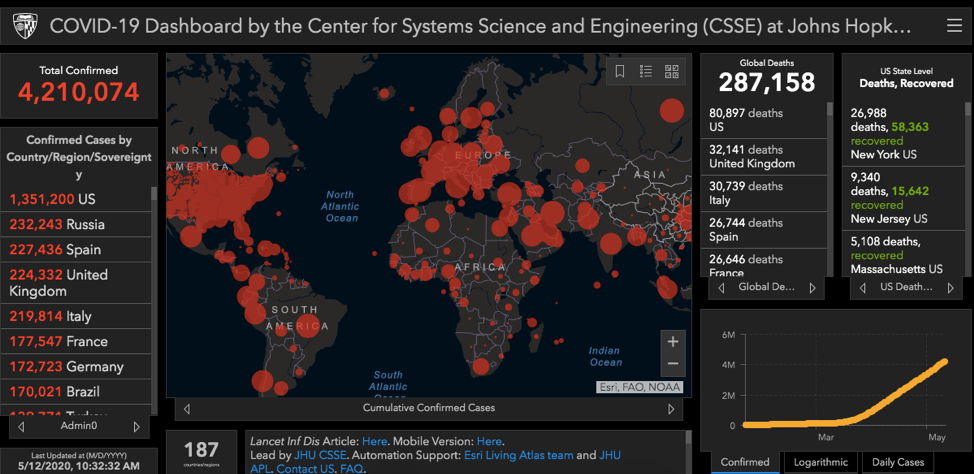

Header image source: Quartz.