Daniel Renfrew- Department of Sociology and Anthropology, West Virginia University

Lead poisoning, the disease of antiquity and the twentieth century’s “mother of all industrial poisons” (Markowitz and Rosner, 2002), continues to haunt and cover the earth. Lead is a legacy pollutant of America’s toxic infrastructure, found in the cracked and peeling paints of old housing stock, the pipes and water of post-industrial cities from Flint to Newark, hazardous waste sites both seen and “unseen” (Frickel and Elliot, 2018), and the dust and debris of demolished buildings, while it continues to be found in children’s consumer products ranging from toys and backpacks to baby food. Across the world, countless tons of lead continue to be released through mining and manufacturing in the formal sector, in cottage industries such as informal e-waste recycling, and through spectacular events like the fires that engulfed the Notre Dame cathedral.

Latin America, as elsewhere, is characterized by both extreme and “routinized” forms of lead contamination. The mining and smelting town of La Oroya, Peru has been labeled one of the world’s most polluted places. A Buenos Aires shantytown on the edge of a massive petrochemical complex suffers devastating contamination (Auyero and Swistun 2009; Swistun 2018). Resource extraction, smelting, refining, manufacturing, recycling, and hazardous waste sites proliferate across the region, creating severely polluted “hot spots” of heavy metals and chemical contamination. But as elsewhere in the world, Latin America has experienced decades of pervasive, routinized forms of lead exposure that more often than not remain publicly and scientifically unrecognized and unstudied (Olympio et al, 2017). Much of the region’s urban population has been, according to the limited studies conducted, exposed and contaminated through leaded gasoline combustion, paints and plumbing, cottage industries, and both mass produced and popular artisanal consumer items such as Mexico’s lead-glazed pottery.

Accompanying the dearth of scientific research is the pervasive absence of regulatory and legislative frameworks. While leaded gasoline was eventually and belatedly phased out throughout the region, most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have yet to pass other lead control legislation, and most have not institutionalized blood screening or other public health programs to identify, mitigate and prevent lead exposure (Olympio et al, 2017: 55). The toxic trail of lead continues to permeate cycles of extraction, production, consumption, waste disposal and recycling. But more often than not it remains undiscovered and invisible, a surreptitiously silent epidemic characterized by “slow violence” (Nixon 2011) and “invisible harm” (Goldstein 2017). A central question then is under what circumstances, and with what effects, does lead become scientifically and publicly visible?

My recent book Life without Lead: Contamination, Crisis, and Hope in Uruguay (Renfrew, 2018) based on ethnographic and archival research spanning fifteen years in Montevideo, Uruguay, analyzes the complex factors that made longstanding toxic exposures visible. Guided by the premise that epidemics are not only objectively rendered, but are socially produced or “made” by society, it examines how social and political actors, grassroots activists, journalists, officials and experts transformed lead from a silent epidemic into a publicly recognized toxic event. This research, following a political ecology of health perspective, covers a broad range of questions, themes and sites in examining both the material and structural forces conditioning differential risk and health inequities in Montevideo, and the generative and symbolic dimensions of a public health disaster that brought into being new assemblages, subjectivities, and possibilities for transcending the multiple facets of la crisis.

Lead poisoning was first discovered in 2001 amidst an unfolding economic crisis unprecedented in scope in Uruguay’s modern history. The toxic legacies of the mid-twentieth century Import Substitution Industrialization period, when battery factories and metals smelters dumped waste throughout Montevideo’s empty lots and riverbanks, were exacerbated by the neoliberal crisis that left tens of thousands of people vulnerable and homeless. Many turned to building makeshift squatter settlements, forging new homes and play spaces, on those same toxic landscapes that had previously been unoccupied (photo 1). They sometimes became sites of informal metals smelting and electric cable burning, thereby layering toxics upon toxics. Soil and blood lead contamination at times stretched to extreme levels, the former in the tens of thousands of mg/kg (the U.S. EPA residential limit is 400 mg/kg, Canada’s is 140 mg/kg), and the latter reaching as high as 60-70 µg/dL (the CDC and WHO action threshold at the time was 10 µg/dL, and now it is 5 µg/dL).

Photo 1: La Teja squatter settlement

Photo 1: La Teja squatter settlement

The discovery of a handful of lead poisoned children in western Montevideo’s de-industrializing working class neighborhood La Teja quickly escalated into a public health emergency, where journalists wrote about environmental disease for the first time, silent urban toxics became publicly visible, and residents, parents, children and activists began to forge new understandings of self, place, home and well-being. One of the central arguments of my book is that lead poisoning became visible because it was discovered in La Teja, as activists there were able to tap into rich and radical histories of labor organizing, dictatorship resistance, community solidarity and even the expressive popular arts of Carnival. Thus was born the nation’s first environmental justice movement (photo 2).

Photo 2: Inlasa settlement protest, La Teja

Photo 2: Inlasa settlement protest, La Teja

The state mobilized, creating unprecedented institutional frameworks for environmental health interventions and monitoring. They opened the nation’s first clinic dedicated to environmental contaminants, and started the long and fraught process of relocating thousands of people into new neighborhoods and homes. Lead control legislation was passed, leaded gasoline was phased out in 2004, and the nation’s first environmental lawsuits began to grant redress to victims. In many ways, the lead story forms a new chapter in the country’s long history of impressive public health victories.

The state also de-mobilized. Despite frequent promises, it never conducted a systematic epidemiological study, thereby occluding information on the objective scope of the epidemic, which may have reached into the tens or even hundreds of thousands of children. Public Health officials went to political war with the lead poisoning clinic director and staff, and they downplayed the scope and severity of the epidemic, emphasizing a kind of “pseudo-pragmatism” in an effort to quell grassroots indignation and avoid a public panic. The government enacted a de-facto Official Protocol establishing a blood lead medical intervention threshold of 20 µg/dL, double the international recommendation of the time. Further, it limited environmental studies to soil analyses in squatter settlements, emphasizing the sites of most extreme contamination, but in the process de-emphasizing the routinized contamination of urban space through paints, pipes, and leaded gasoline emissions. Its focus on extreme poverty cemented the connection public health officials often made of the “two p’s” of plomo (lead) and pobreza (poverty). The result was the staging of a cultural politics surrounding lead poisoning. With lead framed as a “disease of poverty,” victims became pathologized agents of their own misfortune, self-poisoned through their purportedly marginal attitudes, uneducated minds, negligent parenting, and unhygienic habits.

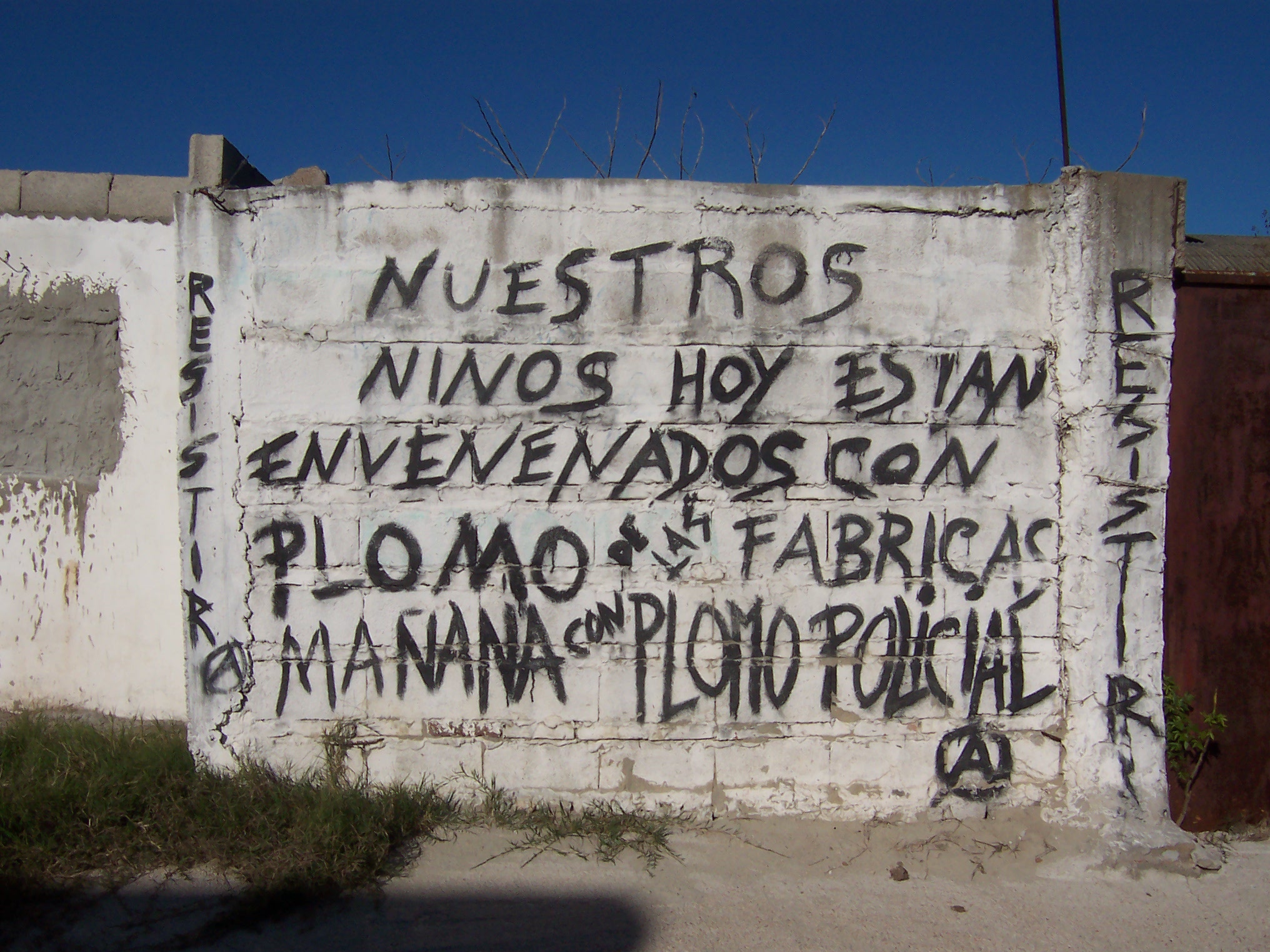

Was lead poisoning ultimately a product of “culture,” or was it the structural reflection of an unjust and unhealthy socioeconomic system? Activists, journalists and allied scientists negotiated this cultural politics, which became one of the central political arenas of the Uruguayan lead issue. At stake were questions of agency and responsibility, with powerful repercussions for public health, environmental and housing policy. “We are not marginals, but they marginalize us,” stated one of the women protest leaders in demanding housing relocation from a severely contaminated squatter settlement occupying an old La Teja metals smelter (photo 2). The anarchist graffiti in neighboring Nuevo París (photo 3) deftly connected the life outcomes of childhood poverty to both structural and state forms of violence and repression. It read, “Today Our Children are Being Poisoned with Factory Lead. Tomorrow with Police Lead.”

Photo 3: Anarchist Graffiti, Factory and Police Lead

Photo 3: Anarchist Graffiti, Factory and Police Lead

Ultimately, environmental justice activists like lifelong La Teja resident Carlos Pilo were challenging a system that subjugated the lives of workers and the poor to chronic unemployment, poverty, environmental disease and pervasive disrespect. “Because we were poor, black, and from La Teja,” Pilo recounted, “we gathered all the conditions for no one to care.” Nevertheless, La Teja’s environmental justice movement, led by mothers, squatter residents, labor activists, old anarchists, community journalist youth, pediatricians and allied professionals, did force the media and society to take notice, and ultimately the state to act. From embodied suffering and emotional despair, through the embers of an unfolding public health disaster, they were able to make a silent scourge visible, forging a new sense of possibility and hope.

Works cited

Auyero, Javier and Débora Swistun. 2009. Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frickel, Scott, and James R. Elliot. 2018. Sites Unseen: Uncovering Hidden Hazards in American Cities: London: Sage.

Goldstein, Donna. 2017. “Invisible Harm: Science, Subjectivity and the Things We Cannot See,” Culture, Theory and Critique 58(4): 321-329.

Markowitz, Gerald E., and David Rosner. 2002. Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Olympio, Kelly Polido Kaneshiro, Cláudia Gaudência Gonçalves, Fernanda Junqueira Salles, Ana Paula Sacone da Silva Ferreira, Agnes Silva Soares, Marília Afonso Rabelo Buzalaf, Maria Regina Alves Cardoso, Etelvino José Henriques Bechara. 2017. “What are the blood lead levels of children living in Latin America and the Caribbean?” Environment International 101: 46-58.

Renfrew, Daniel. 2018. Life without Lead: Contamination, Crisis, and Hope in Uruguay. Oakland: University of California Press.

Swistun, Débora. 2018. “Cuerpos abyectos: Paisajes de contaminación y la corporización de la desigualdad ambiental,” Investigaciones Geográficas 56: 100-113.