Efren Legaspi, Citizen of Horcón (V Region of Valparaíso, Chile)/Universidad de Sevilla.

‘El aire está malo’ (‘the air feels bad´) is a common expression among people from the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay (V Region of Valparaíso, Chile), who must deal with the atmospheric emissions generated by the industrial complex Ventanas on a daily basis. In the past, such a zone was known for the great quality of its fish and vegetables. Instead, today, the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay is known for the environmental degradation resulting from its industrial development. So much so, that, currently, it is publicly recognized as a ‘sacrifice zone’, a term used in Chile to refer those territories whose inhabitants are (literally) sacrificed to pave the way towards economic progress.

Living in the middle of a sacrifice zone, as the author of this contribution does it, is not easy. Indeed, it poses serious challenges not just for people’s health, but also for their usual ways to know the world and even for their more basic political freedoms. In this context, ‘el aire está malo’ summarizes not just people’s relationship with the air in the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay, but also other aspects of their daily life, as we will explore in this brief reflection.

Ignorance production in the Puchuncaví-Quintero bay

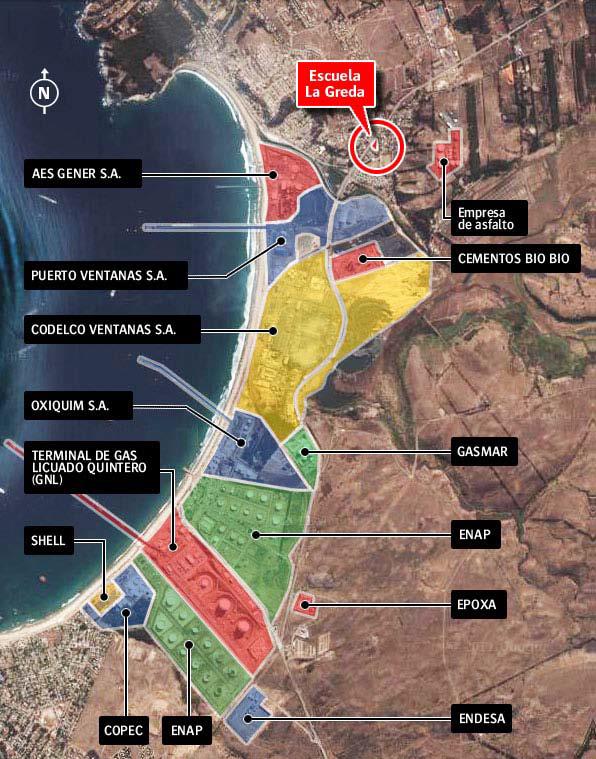

In the 1960s, the Chilean corporation ENAMI (Empresa Nacional de Minería/National Mining Corporation) opened a smelting plant in the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay. Two years later, the first carbon-based thermoelectric plant started to operate in the same area, which, in turn, was followed by hydrocarbon plants, chemical storage warehouses, a regasification plant, cement industries, and more thermoelectric plants, among other highly polluting facilities. In doing so, the so-called industrial complex Ventanas, the biggest Chilean industrial complex, began to operate.

Image 1: Industrial complex Ventanas (Source: Comisión de Recursos Naturales, Bienes Nacionales y Medio Ambiente, 2011: 4)

From the beginning, the inhabitants of Quintero-Puchuncaví bay raised concerns over the effects of the industrial complex on the environment and, especially, on local agriculture and fisheries. In this context, the political and economic elite justified the opening of the complex based on appeals to patriotic feelings, urging the people to accept ‘some sacrifices’ to allow the progress of the country. Thus, for example, on July 17th, 1957, El Mercurio de Valparaíso, the most important Chilean newspaper, stated:

People must approach this problem with patriotism, and they must accept some sacrifices; otherwise, establishing a smelting plant would not be possible in any place in the country. The industrialized nations have accepted these sacrifices. It is the price of progress. Rain is indispensable for agriculture, but when it rains someone must get wet.

In the 1990s, in the context of the introduction of the first atmospheric emission regulations, the first air monitoring systems started to be applied in Chile. However, in the case of the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay, the very same corporations to be scrutinized assumed the management of such systems, so, at the end of the day, they decided what people can and cannot know about the substances that they are breathing in. In this context, it is not strange that, in environmental emergencies, corporations tried to hide information by arguing that monitoring systems are under maintenance, forcing the government to pay for private consultancies in order to know the causes behind such emergencies.

One of the latest emergencies happened in August 2018, when a toxic cloud descended on the bay causing significant levels of intoxication among locals. In this context, officers from ONEMI (Oficina Nacional de Emergencias/National Emergency Office) arrived at the bay to announce the application of a new technology to measure atmospheric substances. After being applied, this new technology detected the presence of methylchloroform in the air, a chemical substance banned by the Montreal Convention, which was signed by the Chilean State in 2015. However, Chilean authorities dismissed this finding, arguing that it was just a mistake related to the lack of experience of the technicians in charge of managing the new equipment.

So far, there is not a clear answer for what happened in the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay in August 2018. While some authorities argue that the public corporation ENAP (Empresa Nacional de Petróleo/National Oil Corporation) holds primary responsibility for it, executives and workers from this industry argue that it does not use any of the substances related to the intoxication. Meanwhile, the industrial complex Ventanas continues operating without restrictions, and people continue to be exposed to the effects that chemicals, corporations and the state leave on their bodies.

‘El aire está malo’ reflects not just the poor quality of the air that people from Puchuncaví-Quintero must breath every day. It is also a clear expression of the atmosphere of the corporate and political irresponsibility that impacts the whole bay.

Sacrificial knowledge

After every critical episode, state and corporate agents try to calm people. Sometimes, they do it by promising environmental assessments and new protocols to enhance air quality. Alternatively, they dismiss people’s concerns by arguing that, as was stated by the Chilean Health Minister in 2018, they are breathing ‘inoffensive odours’. In any case, the main goal is leading people to forget the toxic atmosphere where they live in, suggesting that its effects on their health can be easily solved or, simply, that such effects do not exist at all.

In response, the people from the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay try to pay attention (Stengers, 2017) to several details of their daily life in order to reveal the chemical excesses (Tironi, 2014) that they face. As has been widely explored by Tironi (2018), in some cases, they pay attention to their animals and plants, whose behaviour is assumed as an indicator of the presence of “something rare in the air” (Tironi, 2017). That is the case, for instance, of Fernando Robles, a farmer from Los Maitenes:

[In Los Maitenes] everything is dead [because of the pollution]. Cows started to walk in circles, and after they died … after that, ships started also to die … Even the grass died. We had to stop eating fruit from trees…

Likewise, people pay attention to the reactions experienced by their own bodies as they interact with the chemicals being emitted by the industrial complex, such as can be inferred from the following conversation with Juana Rivera from Quintero:

Today I can distinguish the toxic cloud, I can distinguish the intensity of the [pollutants] through the first breath… it is terrible. I know that if I strongly feel oxide smell [the pollution level] is a little bit bigger than 1500 SO2, [in such a case] I feel my chest closed, I cannot breathe easily, I feel exhausted … When going to my work and crossing the industrial complex I feel dizzy, I feel that I am going to vomit…

Faced with the confusion produced by corporate and state agents, people’s bodies, along with their animals or plants, act as bioindicators, appearing as the most reliable source to make visible the chemical excesses that affect the Puchuncaví-Quintero bay. However, it is important to note that, instead of being based on a purely contemplative exercise, this bodily knowledge (Shapiro, 2015) requires a sacrifice, namely: being willing to be affected by the pollution. Indeed, it is through the recognition of the traces left by the industrial development on the human body, and the resulting mimesis between the former and the latter, how people from the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay can uncover the pollution that surround them.

In brief, in places like Puchuncaví-Quintero, making sense of the territory, instead of being a purely intellectual issue, is a bodily experience, which, in many cases, can actually hurt. In this regard, ‘el aire está malo’ reflects not just the poor quality of the air, but also the sorrow that people can feel when trying to understand the place where they live.

Pollution as body repression

In May 2019, the Supreme Justice Court of Chile released a ruling regarded as a milestone, as, for the first time, it acknowledges that, in the Puchuncaví-Quintero bay, the Chilean state has continually violated the constitutional right to live in a non-polluted environment. Besides, this ruling establishes that the state must urgently apply several measures, such as carrying out toxicological tests on the population, ensuring medical supervision in critical cases, establishing a public network to monitor atmospheric emissions, and identifying all the dangerous substances affecting the air.

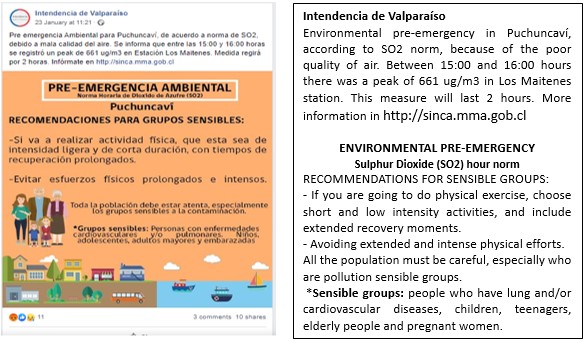

So far, none of such measures have been applied and the people from Quintero-Puchuncaví continue to be treated as if their constitutional right to live in a non-polluted environment is not valid. Similarly, other rights are continuously cast into doubt, which is especially visible in the context of environmental emergencies; in these cases, the local government releases announcements urging people to breath slowly and avoid practicing physical activities, eroding, at least in some extent, their freedom to govern their own movements.

Image 2: Recommendations for environmental emergencies (Source: Intendencia de Valparaíso’s Facebook account https://www.facebook.com/intendenciavalparaiso/photos/a.170030323276739/1309316752681418/?type=3&theater)

In this context, ‘el aire está malo’ reflects not just the poor quality of the air, but also the fact of living under a permanent state of exception (Agamben, 2005) where people cannot exert complete control on their own bodies.

Hope

‘El aire está malo’ reflects the rarefied atmosphere that involves the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay; an atmosphere that virtually involves every dimension of daily life, and that reflects the affection not just of air, but also of ways of making sense of world and practicing basic political freedoms.

Despite everything, people from the Quintero-Puchuncaví are not willing to be treated like disposable beings, beings whose lives, ultimately, do not matter. In this context, social organizations like the NGO Movimiento por la Infancia de Quintero (Movement for Children from Quintero) have assumed the task of sharing information every time that atmospheric pollution surpasses the levels recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), counting the environmental emergencies throughout the year, and denouncing the loss of information from monitoring stations.

Movements like such an organization are not few in the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay. On the contrary, there are many people who, inspired by the desire of caring for their families and neighbours, try to articulate new citizen strategies to scrutinise corporations and State. No doubt, these kinds of actions are not enough to solve the environmental problems affecting the Quintero-Puchuncaví bay, but they are a clear expression that, in spite of having experienced decades of environmental violence deliberately organized by State and corporate actors, people have not yet given up hope of living in a place where saying ‘el aire está bueno’ (‘the air feels good’) be possible.

References

Agamben, G. (2005). Estado de excepción. Homo sacer II, 1. Argentina: Adriana Hidalgo Editora.

Comisión de Recursos Naturales, B. N. (2011). Informe de la Comisión de Recursos Naturales, Bienes Nacioanles y Medio Ambiente a fin de analizar, indagar, investigar y determinar la participación de CODELCO y empresas asociadas, en la contaminación ambiental en la zona de Puchuncaví y Quintero. Valparaíso: Congreso Nacional de Chile. Obtenido de https://www.camara.cl/pdf.aspx?prmID=45601&prmTIPO=INFORMECOMISION

Shapiro, N. (2015). Un-knowing exposure. Toxic emergency housing, strategic inconclusivity and governance in the US Golf South. En E. Cloatre, & M. Pickersgill, Knowledge, technology and law (págs. 189-205). OX: Routledge.

Stengers, I. (2017). En tiempos de catástrofes. Cómo sobrevivir a la barbarie que viene. Barcelona: NED.

Tironi, M. (2014). Hacia una política atmosférica: químicos, afectos y cuidado en Puchuncaví. Pléyade (14), 165-189. Obtenido de http://www.revistapleyade.cl/wp-content/uploads/14-Tironi-5-de-nov.pdf

Tironi, M. (2016). Algo raro en el aire: sobre la vibración tóxica del Antropoceno. Cuadernos de Teoría Social, 2(4), 30-51. Obtenido de http://www.cuadernosdeteoriasocial.udp.cl/index.php/tsocial/article/view/26

Tironi, M. (2018). Hypo-interventions: Intimate activism in toxic environments. Social Studies of Science, 48(3), 438-455. doi:10.1177/0306312718784779