Adrian Gonzalez, University of York

[email protected]; Twitter: @AGonzalez05

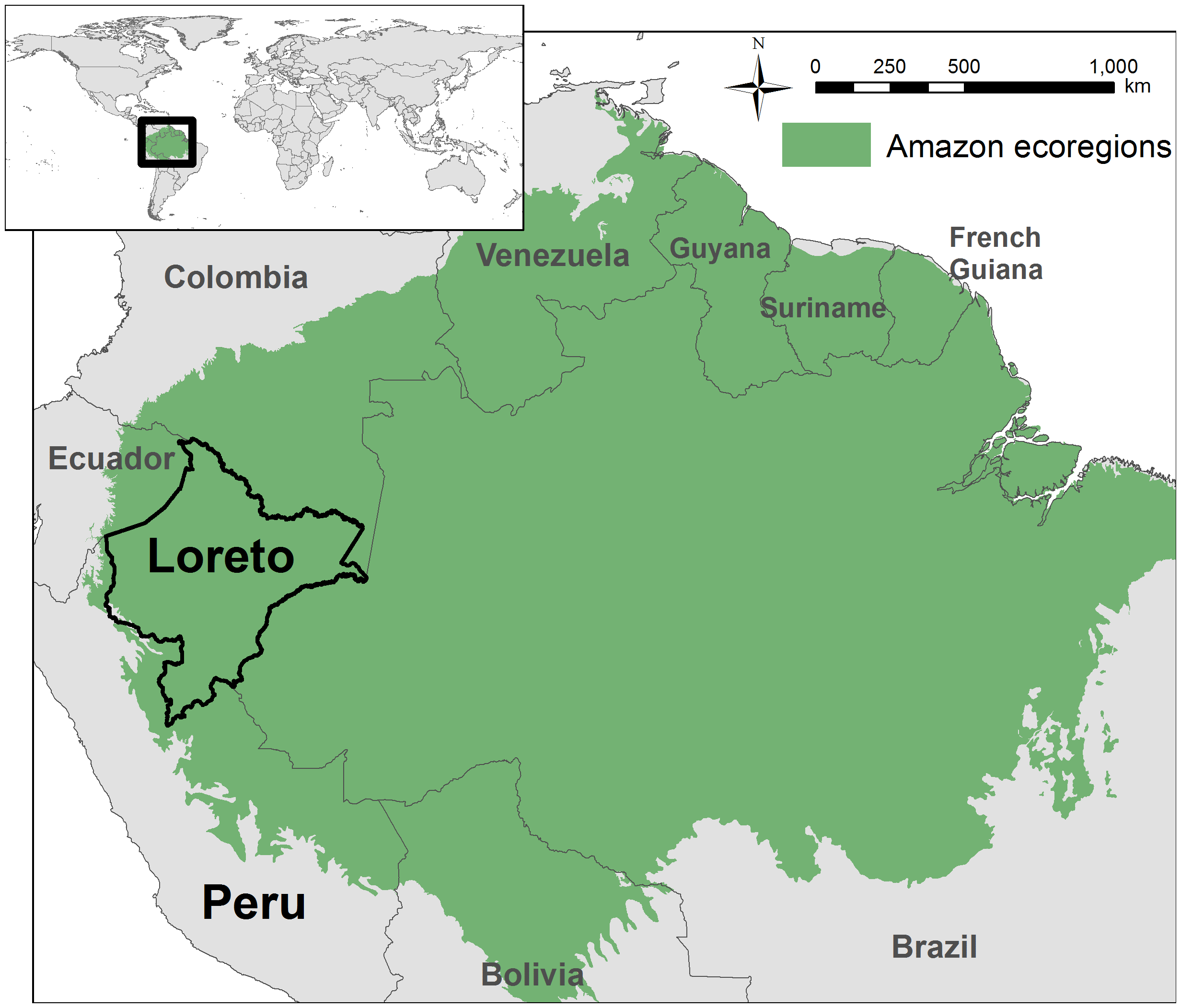

Imagine you and your family suffering from the effects of oil pollution and feeling powerless to report it and seek justice. My research shows that this is the situation that rural Peruvian communities face today. Two villages in Peru’s Amazon region of Loreto have both been affected by oil pollution caused by the state-run company Petroperu.

Petroperu has allegedly used a mixture of fear and bribery to try and prevent these villagers from reporting these spills to the authorities and their mistreatment during the clean-up work. Petroperu deliberately tried to silence them, a situation only prevented by the courage of individual citizens and their links to outside actors.

Amazon pollution and justice

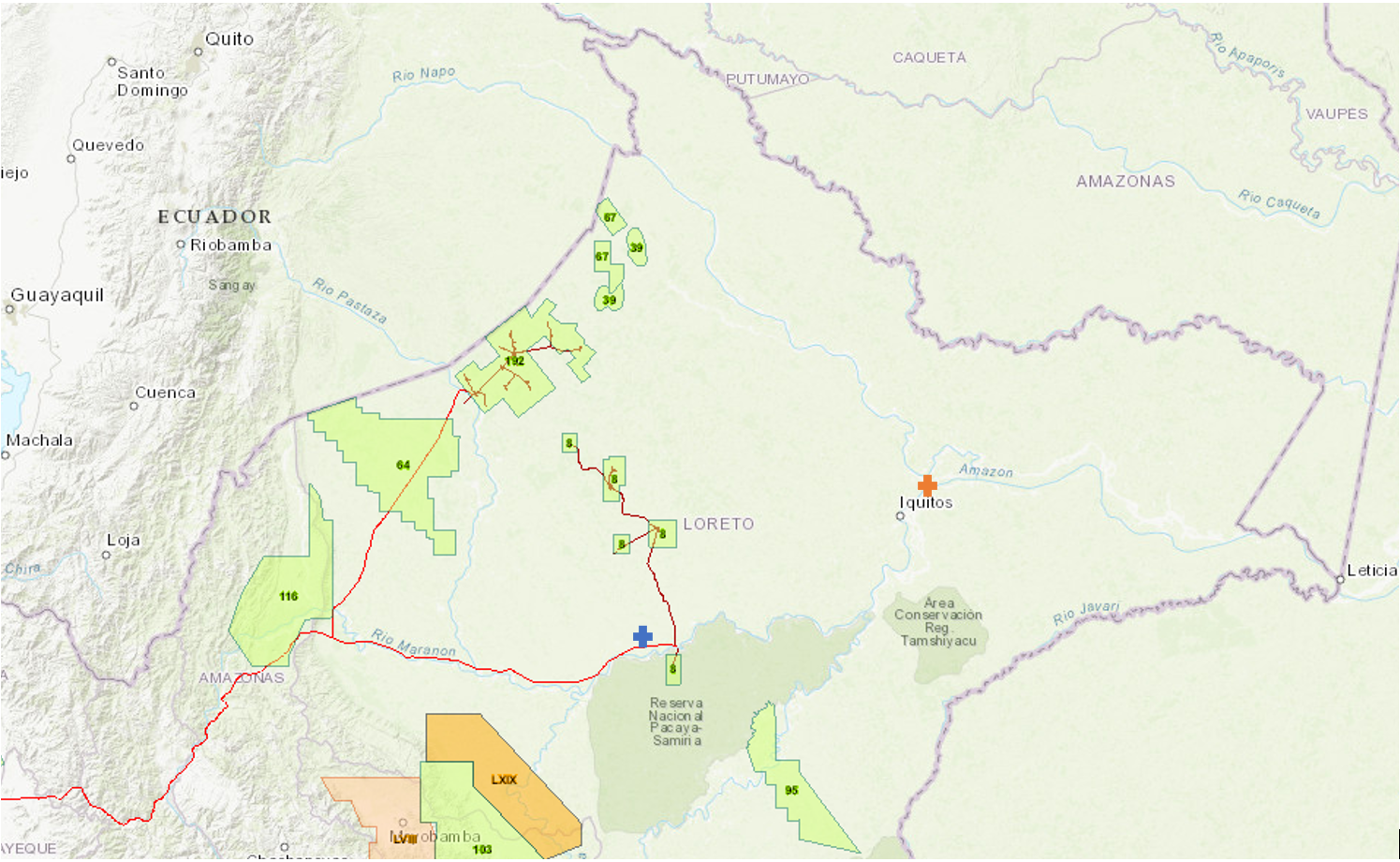

Peru’s Loreto Region is one of the country’s main oil locations. Petroleum is transported hundreds of kilometers to refineries located on the Pacific coast via the North Peruvian pipeline, operated by Petroperu. However, over many decades there has been significant pollution in several oil sites and from the pipeline, caused by poor operational practices and weak regulation. In 2016 alone, seven pipeline incidents occurred, spilling an estimated 10,000 barrels of oil into the Amazon and its tributaries. More recent spills have been reported in November 2018 (8,000 barrels) and June 2019 (affecting 1,230 families). According to OEFA, the government environmental monitoring agency, since 2016, more than 20,000 barrels of oil have spilt from the pipelines in 15 vandalism attacks and 5,600 barrels have been lost due to corrosion or operational failures.

I have been exploring whether Peruvian communities can report these spills and hold oil companies accountable for the pollution and if they can access and gain environmental justice. I focused on Petroperu and two of its pollution-affected communities; Barrio Florido, situated on the Amazon river, 30 minutes downriver from Iquitos and adjacent to the Petroperu refinery and Cuninico, a Cocama indigenous community located in the heart of the Amazon, 11 hours by speedboat from Nauta, the port city of Iquitos, and in close proximity to the North Peruvian pipeline. Their ability to report spills and seek justice is very difficult.

This is partly because of the State. Peru is intent on achieving a highly neoliberal development agenda in the Amazon and further afield. This includes consolidating and expanding its oil Blocks, mining projects and Camiesa gas pipeline, and implementing 20 large-scale dams along the Amazon river system, the biggest of which, on the Manseriche, could flood 5,470 square km. Other significant projects include transport infrastructure such as the Amazon Waterway Project, a major scheme that will deepen and widen the Amazon and other tributaries to improve navigability for larger vessels and a Chinese backed 5,300 km Amazonian railway to connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts to reduce commodity transport costs. Peru is implementing these projects without offering citizens the opportunity to provide free, prior, and informed consent. Hearing that there are problems with oil production or mining doesn’t fit this agenda.

Equally, discrimination means that State officials don’t regularly visit or invest in indigenous communities. Villages lack basic infrastructure such as roads, electricity, clean water or medical and educational facilities leaving them poorer, more isolated and dependent on oil companies. As one resident of Barrio Florido commented to me ‘como un cero a la izquierda’ (we are a waste of space, here there is nothing). These issues, alongside rural poverty, also act as barriers to citizens accessing environmental justice through the state.

Petroperu and its “climate of fear”

Amazon communities can be dependent on oil companies for many things such as jobs, clean water or electricity, a situation occurring in Barrio Florido. Here Petroperu’s refinery supplies their electricity and provides manual labourer employment. Its proximity means that residents should easily be able to report pollution issues.

However, Barrio Florido’s Petroperu dependency means that residents are afraid to voice objections about problems or seek environmental justice. People spoke about long-running rumours suggesting that the village’s electricity would be cut off or that labourers would lose their jobs if they spoke against Petroperu. A “climate of fear” hangs over them, a situation suiting the company who have less worry about improving their operational practices.

In Cuninico’s case, despite proximity to the Petroperu operated North Peruvian pipeline, they have never visited to establish reporting procedures. When a spill occurred in 2014, villagers were only able to contact Petroperu through a telephone number found in a school book supplied by the company. They had no other means of communication.

Upon arrival at Cuninico, Petroperu offered them clean-up jobs in exchange for their silence. Given their poverty, they accepted. This was pure exploitation by Petroperu. Cuninico and other indigenous villagers were given the most difficult and dangerous task of locating the pipeline break without any training, protective clothing or heavy equipment. A Cuninico worker recounted that ‘to try to lift the pipeline, we had to immerse in that water without any protection … under the instruction of engineers, they told us that we had to try to reach it, so we did immerse there without any clothing, only underwear and it was full of crude oil, it was thick.’

Petroperu also allegedly employed under-age children who worked in these appalling conditions. Oil workers, who have developed long-term health problems were warned not to speak out otherwise they would lose their jobs. After four months, Petroperu left Cuninico but failed to provide villagers with enough food or clean water, an issue still being recently reported.

Breaking Petroperu’s climate of fear

How was this climate of fear broken? In Barrio Florido, not all residents are refinery employed which meant that two were willing to phone a radio station to report the contamination. In Cuninico, the community leader’s unwillingness to be bribed and their connection to a trusted outside actor (the Catholic Church) meant they were able to alert authorities to the spill and through them, seek justice. So, strong courageous citizens and links to outside actors can help. Nevertheless, this doesn’t always happen. Another indigenous community valued their jobs at a North Peruvian pipeline pumping station rather than using their Catholic Church links to report the spill.

Supressing citizen voice

Overall, this research has found that Peruvian Amazon communities can be forced to stay silent about oil pollution. The absence of state contact or infrastructure makes them heavily dependent on oil companies who can use this situation to their advantage. Petroperu used a climate of fear to silence local people which is sometimes only successfully broken by courageous individuals or links to trusted outside actors. Holding these actors accountable and accessing or gaining justice is extremely difficult for rural citizens, especially for indigenous communities who face the added barrier of discrimination. It forces them to become reliant on non-state actors, like the Catholic Church or NGOs for access to justice and increases the likelihood of violent protest and other radical action, by people attempting to make their voices and injustice situations heard.

Therefore, Petroperu is using sub-standard practices against citizens it knows will struggle to challenge them. Cuninico’s experiences are not unique as recent oil spills indicate similar indigenous employment, including reports of child workers. Petroperu has little interest in stopping its discriminatory, abusive and exploitative practices against indigenous people who will face a struggle between reporting contamination and seeking justice on the one hand and staying silent on the other.

Note: please email me for copies of any of my academic papers described and hyperlinked in the article.