Amelia Fiske [email protected]

Institute for History and Ethics in Medicine, Technical University of Munich

It is mid-June 2012, and I have travelled from the Amazon to the southern highlands of Ecuador, to see Pablo Cardoso’s exposition of Lago Agrio-Sour Lake in the artist’s home city of Cuenca.[i] Lago Agrio-Sour Lake merges art and activism to explore how the consequences of oil extraction in the northeastern Ecuadorian Amazon relate to the colonial legacies of United States companies operating in Latin America (see here for the artist’s webpage and here for the Galeria Proceso’s blog post on the exhibit). As an anthropologist who had been conducting fieldwork in the Amazon region over the course of two years, I was interested in the ways that Lago Agrio-Sour Lake reversed the journey of toxicity between North and South America; instead of an American company arriving in the Amazon to extract ‘black gold,’ instead was a tale of an Ecuadorian artist returning the waste to its geopolitical origin in Texas. This was an environmental justice homecoming tale, told through art.

Travelling to Sour Lake

Named after an auspicious source of sulfurous water in a nearby lake that foretold the presence of crude oil below, Sour Lake, Texas, is the hometown to the Texaco Company. Founded in 1903, just two years after the discovery of oil there, Sour Lake formed part of the beginning of the Texas oil boom at the turn of the century. Some 60 years later, Texaco oil workers arrived in Ecuador to begin operations. The name “Sour Lake” was translated and transposed onto the new Texaco oil camp in the jungle. Although the official name of the city is Nueva Loja, given by the many Lojano settlers that had founded the city alongside the Texaco camp in Ecuador, today Lago Agrio has been adopted as the unofficial name of the city. The title of Cardoso’s work highlights the indelible connections of oil, extraction, and power between these two namesakes.

Upstairs from the narrow cobblestone streets in a narrow exposition room of the Cuencan gallery, 120 sepia-toned paintings wrap around the length of the walls. The linear nature of the display invites viewers to begin at the first painting over to the far left of the room, with the line of images wrapping around three walls of the room at eye level. In the first, gloved hands open the valve of an oil well to fill a plastic bottle. A penciled number in the corner annotates the order of the work, reinforcing the sequential progression of the viewer through the series. In the second painting, the gloved hands carefully pour the substance from the plastic bottle into a small glass vial with a black top, the sort of vial used for scientific sampling. The vial of toxic water, balanced on the open palm of the gloved hand in the third frame suggests a murky opacity when held up against the light of the jungle tree line.

The paintings that comprise Lago Agrio-Sour Lake document the journey of a vial of toxic formation waters.[ii] The vial travels from the oft-imagined ‘margin’ to ‘center,’ traversing the geopolitical relationships between the US and Ecuador in the recent history of oil development. Beginning with the moment the vial is filled with formation waters from an old Texaco well in the Amazon, the paintings follow the vessel as it travels by car to Quito, boards a plane and flies 2,343 miles north to Houston, where it is then driven to Sour Lake, Texas. Along the way, the bottle passes by oil pipelines and shadowy silhouettes that are evocative of the winding road leads travelers out of the Amazon, and up over the Andes.

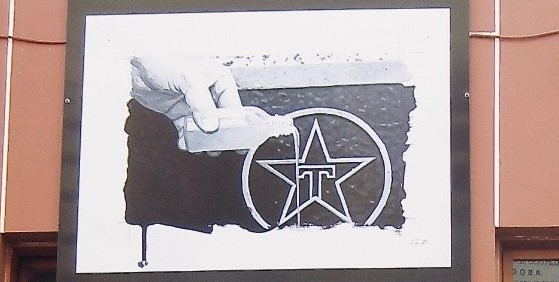

The infrastructure of bridges and power lines frame the bottle as it moves through Andean fog. The blurred lights of Quito plazas at night, the sticky seatback pocket of an airplane, and the leftover remains of a meal suggest the passing of time and changing of spaces as the bottle makes its way North. Finally reaching the US, highway signs cue the viewer as the bottle travels from Houston to Sour Lake, the hometown of Texaco. As the bottle makes its journey, it inches closer and closer to the home of the oil industry in the United States. Reaching Sour Lake, the journey is complete. In the final frame, the contents of the bottle are poured – caught in a silent, deliberate, perpetual stream – onto the Sour Lake well. The star of the Texaco logo blazes in the background. Some 3,000 miles and more than a century of toxic exchange are conjured through Cardoso’s 120 images.

Reversing the Journey

While oil workers set their sights on the Amazon, Lago Agrio-Sour Lake begins in Ecuador in order to trace the steps of toxic production back to Texas. Like the destination marker posted over the windshield on a bus, the name of the artwork marks the origin and destination of the trip. Lago Agrio-Sour Lake is an invitation to a journey through space, but also in time, to question decisions made in the past half century about nature, politics, and toxicity in the making of contemporary oil development in the Amazon. For Cardoso, the return in time is an invitation to query how we arrived at the present moment and what we alternative possibilities we might desire for our collective futures:

This work is an invitation to travel through time, to go back to 1903 when the first oil well was drilled in Sour Lake, the first Texaco well. If we could go back to that moment, and if we had the knowledge that we now have regarding the impacts of the oil industry, and [if we knew] that global civilization would depend more and more and more on oil, what decisions would we have taken in that moment?[iii]

The journey from Lago Agrio to Sour Lake reverses the relations implicit in so many journeys that have been taken from North to South in the Ecuadorian Amazon, harkening back to colonial times (Latour 1988; Manthorne 1989; Fontaine 2007). This is a critical, intentional movement in which one vial of the reported 19 billion gallons of toxic waste that were dumped by Texaco into Amazonian rivers is returned to its owner in Texas (Kimerling 2013). For Cardoso, it is an assertion of unambiguous responsibility on the part of Texaco for the environmental harm enacted in the Amazon. Yet the work also goes beyond a simple critique of Texaco’s actions in the past and moves to question the continuation of extraction in Ecuador today by the state and other foreign companies.

In returning toxic waste to Texas, Cardoso asks viewers to contemplate different possibilities for life on the planet. The opening of the Lago Agrio-Sour Lake exhibition in 2012 dovetailed with ongoing debates in Ecuador about the future of mining and the opening of oil fields in the Yasuní (Fiske 2017). His work relates to current of responses, including those linked to the Aguinda v. Texaco lawsuit, that have critiqued extraction as a continuation of colonial toxicity and called for an end to future oil exploration in the Amazon. For Cardoso, returning to Sour Lake is an opportunity to pause, and reconsider the direction that these wells have taken ‘us’ in Ecuador, the United States, and beyond. While taking up the specific history of Texaco in Lago Agrio, his critique is ultimately much broader, extending to questions of resource dependency, waste, and environmental justice.

A place often imagined as the locus of planetary biodiversity for its ‘excessive nature,’ the Amazon, as the iconic marker of the Tropics and dreams of human conquest, lends itself easily to myth (Raffles 2002). The Ecuadorian Amazon has long been a place of desire within national and international imaginaries: as a set of natural resources, a symbol of one of the world’s last “wild frontiers,” and more recently as a site of environmental and social activism in response to the consequences of the oil industry (Hecht and Cockburn 2010). In the past half century, the Amazon has emerged as an object of concern within environmental movements at the same time that it increasingly became an object of extraction for global energy desires. Yet, many of the present-day entanglements of industry, environmental conflict, and toxicity have a much longer historical arc. More than just a journey into the past, Cardoso’s work is an invitation to think about how we represent colonial legacies that are entwined with histories of industry and toxicity in contemporary environmental justice struggles. Building on Cardoso, how else can we continue drawing these connections, to articulate the ephemeral, entangled trails of toxicants across the places we work, love, and call home?

Works Cited

Fiske, Amelia. 2017. “Natural Resources by Numbers.” Environment and Society 8 (1): 125–43.

Fontaine, Guillaume. 2007. El Precio Del Petroleo. Quito, Ecuador: Editorial Abya Yala.

Hecht, Susanna B, and Alexander Cockburn. 2010. The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers, and Defenders of the Amazon. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

Kimerling, Judith. 2013. “Lessons from the Chevron Ecuador Litigation: The Proposed Intervenors’ Perspective.” Stanford Journal of Complex Litigation (SJCL) Volume 1 (Issue 2): 241.

Latour, Bruno. 1988. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Harvard University Press.

Manthorne, Katherine. 1989. Tropical Renaissance: North American Artists Exploring Latin America, 1839-1879. New Directions in American Art. Washington, [D.C.]: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Raffles, Hugh. 2002. In Amazonia: A Natural History. Princeton University Press.

[i] To see more images of Lago Agrio-Sour Lake, please visit Pablo Cardoso’s personal website: http://www.pablocardoso.com/.

[ii] Petroleum is refined after separating crude oil, gas, and water that exist as slurry in underground pockets. The water that is part of the underground solution is referred to as “production waters” or “formation waters.” This water varies in composition by location, and is characterized by high salinity, the presence of hydrocarbons, and naturally occurring radioactive material. It also contains high levels of benzene, chromium-6, and mercury. Difficult to manage since they rapidly corrode pipelines and storage tanks, production waters are highly toxic to humans, animals, and plants.

[iii] Cardoso’s original quote in Spanish is: “Esta obra también es una invitación a viajar en el tiempo, a retroceder a 1903 cuando se explota el primer pozo petrolero en Sour Lake, el primer pozo de Texaco. Si retrocediéramos a ese momento, y tuviéramos el conocimiento que ahora tenemos sobre el impacto que tiene el desarrollo de la industria petrolera y que la civilización global dependa más y más y más de petróleo, que decisiones hubiésemos tomado en ese momento?”