David Brown, University of Warwick

The environmental justice paradigm has its origins in the United States in the 1980s, as a social movement which aimed to tackle the uneven distribution of toxic waste sites and polluting industries located in minority and socio-economically deprived neighbourhoods. Much of the early environmental justice research focused efforts on issues, struggles and conflicts in the industrialised nations (Bullard 1992; Williams and Mawdsley, 2005). However, environmental justice scholarship has extended from a US-centric movement and academic project towards one which is global, dynamic and plural in scope (Scholsberg, 2004; Sikor and Newell, 2014).

As Walker (2009) detailed, environmental justice research has undergone a ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ expansion, with the emergence and diffusion of environmental justice ideas and framings in new settings around the world and the increasing engagement with transnational environmental justice issues and concerns, notably pertaining to climate change. Recent theorising has encompassed scalar research, in seeking to locate local struggles within broader discussions of ecological rights, climate justice and environmental sustainability (Schlosberg, 2004; Barrett, 2014).

However, moving beyond this, there is a need to closely examine and fully contextualise environmental justice issues and struggles in the Global South as situated in specific socio-economic, political and postcolonial settings, “rather than using them as ciphers and symbols of distant ‘others’” (Williams and Mawdsley, 2005). Instead of simply exporting Eurocentric understandings of justice to the rest of the world, we must make sense of how environmental crises and injustices emerge in particular contexts in the Global South, as well as how these connect to macro forms of inequality, global capital, socio-economic relations and colonial legacies. Relatedly, scholars (Schlosberg, 2004; Sikor et al, 2014) have increasingly interrogated ‘recognition’ forms of environmental injustice in interrogating whose visions and values of the environment are recognised and/or prioritised. Here, it is advocated that we should move towards plural, multiple understandings of environmental justice issues and conflicts.

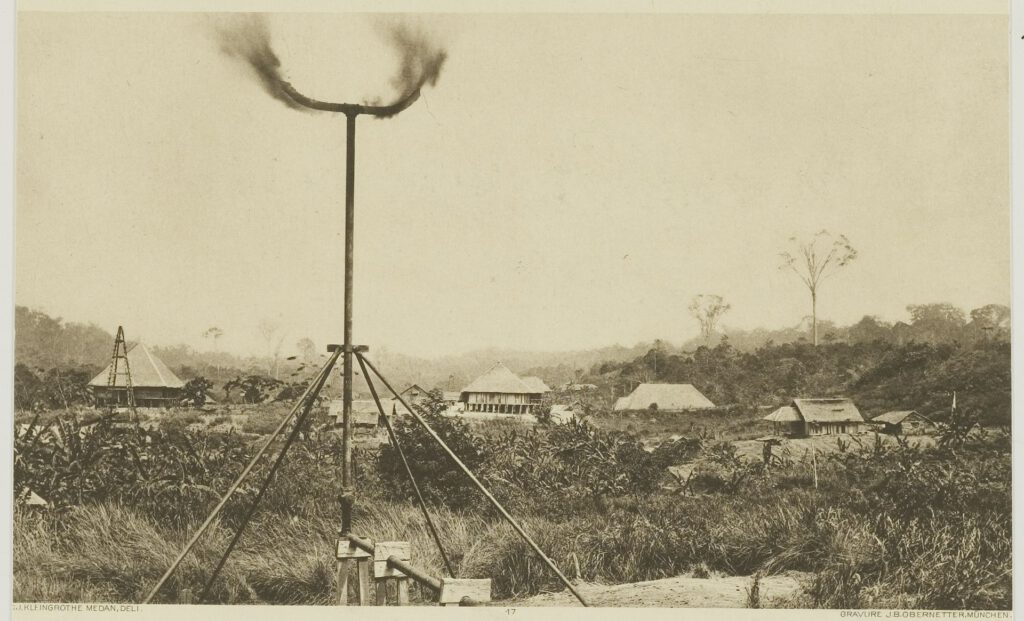

Petro-capitalism was founded on unequal North-South relations and uneven geographies of extractivism, industrial pollution and toxicity (for instance- see the cover photo of Royal Dutch Shell’s first oil well, located in North Sumatra, Indonesia, considered to be the origins of the multinational company when it was built in 1890). Fundamental to the ‘Capitalocene’ (Moore, 2016) is the externalisation and displacement of critical social and environmental costs, not least climate change impacts, significant biodiversity loss and tropical forest destruction, to ‘peripheral zones’. Accordingly, many historical and contemporary environmental crises in the Global South are tightly bound up with imperial legacies, unequal power relations and economic structures.

Over the years, environmental justice scholars and political economists have engaged with concepts of ‘unequal ecological exchange’ and ‘ecological debt’: the idea that ‘ecological capacity’ (e.g. soil degradation, depletion of fish stocks) has been drained and plundered in the Global South in order to directly feed growth in the North (Yu, Feng and Hubacek 2014; Paterson and P-Laberge 2018; O’Hara, 2009). In other words, there are structural connections between the environmental burdens borne in the ‘periphery’ and the economic benefits gained in the ‘core’. Here, the North is seen to maintain domestic environmental standards, while exploiting “high amounts of biophysical resources from the peripheral economies in the South…” (Giljum and Eisenmenger 2004: 14).

Unequal North-South relations are evidently a legacy of colonialism; however, imperialist social and economic relations continue today. Notably, the complex web of global production networks and trade patterns are intertwined with the movement of material and emissions-intensive production to the Global South, meaning that for Northern consumers, the social and environmental costs of production become hidden ‘out of plain sight’. A perceived process of relative dematerialisation in the industrial nations is being at least partially achieved through the draining of ‘ecological capacity’ in peripheral zones, with, notably, significant greenhouse gas emissions embedded in imported goods to the Global North (Paterson and P-Laberge 2018; Davis and Calderia, 2010). Climate justice advocates suggest that the unequal vulnerabilities of climate change are traceable to historical and contemporary imperial relations, with the Global North’s wealth having been built upon fossil fuels, high greenhouse gas emissions and exploitation of resources in the Global South (Blomfield 2016; Sealey-Huggins, 2017).

While environmental justice and political ecology research on the Global South has typically focused upon extractivism through examinations of ‘petro-violence’ of oil frontiers and struggles over natural resources and livelihoods (e.g. Martinez-Allier, 2002; Watts, 2015), emerging research has begun to explore the uneven geographies of toxicity and industrial pollution in Southern contexts. As we have demonstrated on the Global Petrochemical Map, there are multiple cases of environmental injustices occurring in fenceline communities of the petrochemical industry across South America, Asia and Africa. The ‘slow violence’ (Nixon, 2011) and structural injustices connected to polluted landscapes have been well-documented in Western settings; however, there is a need to better understand the character of environmental injustices and toxic pollution in specific contexts in the Global South, particularly in those areas in which there currently exists a lack of data on environmental conflicts or challenges.

From interdisciplinary perspectives and through geographic case studies, the articles in this issue of Toxic News bring to light environmental justice struggles and the multiple forms of violence connected to environmental crises and toxicity in the Global South. These authors seek to reveal the hidden (social and environmental) costs of production and of the myriad, heterogeneous injustices implicated in the petro-economy. The articles explore issues of justice across space, time and nodes of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries. These contributions highlight the need to join the dots between the injustices connected to both fossil fuel extraction and petrochemical pollution, as forming part of the same ecologically-draining, exploitative and imperialist petro-economy.

Firstly, Lorenzo Feltrin and David Brown introduce and discuss The Global Petrochemical Map, a collaborative project developed by the Toxic Expertise team that seeks to make petrochemical connections around the globe visible and to show the commonalities and differences in communities’ experiences of living and working in close proximity to petrochemical industrial sites. In this article, Lorenzo and David highlight how the map can be fruitfully used to identify common trends and local specificities within the global petrochemical sector, primarily through exploring environmental and labour injustices.

Secondly, David Brown reflects upon the fourth annual Toxic Expertise workshop which took place in May earlier this year at the University of Warwick. The two-day workshop brought together scholars from multiple disciplines, backgrounds and perspectives in exploring research on the petrochemical, fossil fuel and related industries through three core themes: Labour Mobilisation, Risk Perception and Environmental Justice. In this article, David details each of the contributions at the workshop and highlights the cross-cutting themes which emerged over the two days.

Thirdly, Patrick Bond discusses the existing and emergent fossil-fuel developments across South Africa, including in South Durban, and the opposition that these face locally from NGOs, activists and environmental groups. Patrick draws out the challenges faced in developing an anti-fossil fuel coalition and a deeper climate justice movement in South Africa across environmental justice groups, eco-socialist strategists, conservationists and labour activists. Environmental justice activists have faced particular constraints in content in which freedom has been profoundly distorted by neoliberal-nationalist ideology and crony-capitalist practices, including periodic repression of socio-economic rebellions.

Fourthly, Laurie Parsons offers a commentary on the toxicity of fashion supply chains. Moving beyond a containment of toxic fashion, Laurie suggests that toxic injustices (as spatial injustices) are embedded into the fundamentals of society. Drawing from his research on the Blood Bricks project in Cambodia and from his reflections on a trip to The Ruhr in Germany, Laurie argues that the spatial and temporal violence of toxicity embedded in the realities of production, notably in the global Southern powerhouses of labour-intensive industry, are rooted not only in unequal interactions, but unequal attention.

Fifthly, Adrian Gonzalez explores the multiple injustices connected to oil pollution in rural Peruvian communities in the Loreto region. Through research in two villages affected by oil pollution, Adrian highlights how the state-run company Petroperu has allegedly used a mixture of fear and bribery in order to prevent villages from reporting oil spills to authorities and their mistreatment during the clean-up work. Due to their dependency on the oil companies for jobs, clean water and electricity, a ‘climate of fear’ hangs over them, meaning that they have difficulties in seeking environmental justice.

Sixthly, Amelia Fiske reflects upon a trip that she took to Cuenca, Ecuador to visit Pablo Cardoso’s exposition of Lago Agrio-Sour Lake. The exposition merges art and activism to explore how the consequences of oil extraction in the northeastern Ecuadorian Amazon relate to the colonial legacies of United States companies operating in Latin America. Amelia brings to light the ways in which Lago Agrio-Sour Lake reversed the journey of toxicity between North and South America, as an ‘environmental justice homecoming tale’, and the historical and present-day entanglements of industry, environmental conflict, and toxicity.

Finally, Tom Ogwang draws attention to the myriad social and environmental impacts of oil development in Uganda. Since the discovery of oil in 2006, a number of oil projects have arisen across Uganda to produce and distribute oil which have led to vast land acquisition, displacements of communities from their land and livelihoods, and numerous, related social injustices. In this article, Tom explores the cumulative impacts of oil development for project-affected communities in a context in which oil exploration and production is in its early stages.