Dr Thom Davies, University of Nottingham, @ThomDavies

Prelude: Some of the ideas discussed in this Toxic News piece are explored further in two recent academic publications, available here and here (Open Access).

In September 2017, I returned to Louisiana to continue ethnographic research about lived experiences in a region infamously nicknamed ‘Cancer Alley’ – home to the highest concentration of refineries and chemical plants in the United States.

I landed in New Orleans airport and spent a jetlagged night at a drab and ordinary hotel. It was just like other shabby hotels, complete with fake-plastic plants, vomit-friendly carpets, and cigarette-burnt bathtubs. That was until I noticed the wall decorations: lining the corridors were watercolor paintings of old white buildings. Not just any old white buildings, but Plantation houses. It was the first of many reminders that the Louisiana landscape is thickly layered with a complex, violent, and ever-present past. As this short article about the Freetown community in Cancer Alley will explore, it is a past that also intersects with the everyday lives of those exposed to toxic pollution today.

Freetown is a small rural community hugging the west bank of the Mississippi River, half way between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Just like the airport hotel, at first sight Freetown is a rather ordinary place. It hosts unremarkable houses and trailer homes, lapped on each side by sugarcane fields that grow tall in the late September sunshine. From the top of the grass-covered levee, it looks like many other pastoral settlements that line the banks of ‘The almighty Miss’. Yet Freetown also has a profound history. Founded soon after the Civil War, it was the first settlement in Louisiana in which freed slaves could own land.

As the historic marker on the adjacent River Road proudly proclaims, since its establishment in 1872, this antebellum community quickly ‘carved up and cultivated the land’ for themselves. Being able to survive independently on the soil, despite years of discrimination, sharecropping, and Jim Crow laws, was an important marker of community resilience. Many residents still fondly recall their forefathers growing a variety of foods, from butterbeans to pecan trees. During ethnographic research in the area, many shared childhood memories of eating homegrown produce, and netting dinner down by the muddy banks of the Mississippi. That was until industry arrived.

Living intimately with chemicals

Residents spoke about sludge-like residue that hangs around the bottom of trees, and of plants flowering out of season, or not at all.

Today however, the picture is very different. ‘You can’t eat nothing off the ground anymore’ explained one local resident, who like many in this area, has seen the local ecology slowly degenerate over the years. Residents spoke about sludge-like residue that hangs around the bottom of trees, and of plants flowering out of season, or not at all. Others described fruit not ripening, leaves changing color, and verdant trees that were planted by their grandparents suddenly dying. ‘The trees grow at different times…’ described one resident, as we walked around her garden, ‘…They come out, then they go back in, they come out and then go back in’, she recalled. Just as Rachel Carson described in her 1962 book Silent Spring, the Freetown community has been forced to ‘live so intimately with these chemicals’. Part of this enforced chemical-intimacy has meant witnessing the seasonal rhythms of natural life become upended, interrupted and replaced by uncertainty.

According to many residents, the reason for their mutating environment can be seen when you peer through the gaps in the neighboring sugarcane field: massive white chemical storage tanks. These tanks are just some of the 118 storage tanks that have been built within a two-mile radius. They hold a variety of toxic liquids deriving from crude oil, and are often placed just a stone’s throw from people’s homes. A growing and leaky assemblage of petrochemical facilities and pipelines are redefining the area, providing well-paid jobs for some, but also inundating local communities with air pollution and toxic releases. No less than nine major industrial facilities are located nearby, with a further $1.8 billion methanol plant currently under construction, and another plant in the final permitting stages.

The story of pollution in Freetown is far from exceptional. Freetown is at the heart of a region infamously nicknamed ‘Cancer Alley’. A concoction of cheap feedstock, lucrative tax exemptions, and riverside access to deep-water ports has made this region an important site for the global petrochemical industry. According to many residents, this concentration of heavy industry is causing increased illness and premature death. It is a region exposed to what Rob Nixon calls the ‘slow violence’ of pollution.

The region’s plantation past has been transposed onto the toxic geographies of today.

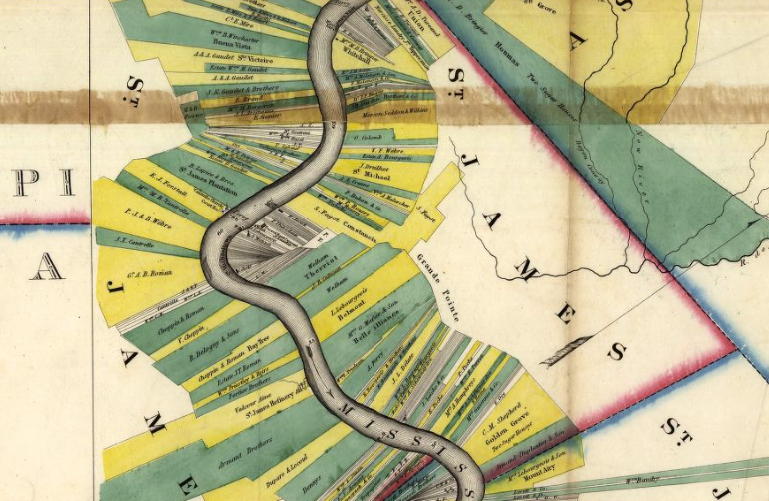

However, the ‘River Region’ – as industry prefers to call it – has an even more violent past. As visualized by the watercolour paintings in the hotel, this part of Louisiana was at the heart of the South’s slave economy. By the 19th Century, around 300 sugar plantations existed between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, divvying up the lower Mississippi and creating what Frantz Fanon called ‘a world divided into compartments’ (1963, 37). Today’s petrochemical plants are intimately linked to this historical geography, as inheritors of a landscape shaped by racial violence. In the post-bellum 20th century, former plantations were sold to nascent oil companies, who were keen to secure a convenient slice of riverside territory. But by setting up polluting industry on the colonial footprint of former plantations, the people who became the most exposed to toxic emissions were the descendants of slaves. In this way, the region’s plantation past has been transposed onto the toxic geographies of today. As veteran environmental justice campaigner Darryl Maley-Wiley explained in an interview at the Sierra Club in New Orleans, the transfer from Plantation to Chemical Plant was effectively ‘exchanging one plantation master for another’.

Freetown, which was built on land that once belonged to the Landry-Pedesclaux slave plantation, is one such example. In this sense, the toxic pollution, which is slowly killing plants and disrupting lives along Cancer Alley, can be interpreted as ‘the noxious residue of American racial history’ (Carl Zimring 2016, 77). This noxious residue is alive and well in St James Parish, where Freetown sits. This summer, the St James Parish Council narrowly approved the controversial Bayou Bridge Pipeline, which will terminate near Freetown, and have the capacity transport up to 480,000 barrels of light and heavy crude everyday. If it is given state approval, this 24 inch wide and 163-mile long pipeline will transfer oil from Lake Charles to St James’ Fifth District, a community that is 95% African American. At the Parish meeting on the 23rd of August 2017, the vote went along racial lines (4-3), with the four white councilmen voting in favor of the pipeline, and three African American councilmen voting against.

The operating company, which holds a 60% ownership in the pipeline, is Energy Transfer Partners – the same company responsible for the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline, which enflamed indigenous activism at Standing Rock. If the Bayou Bridge Pipeline gets the go-ahead, it will form the tail end of a continual network of pipes, running from North Dakota to the Deep South. However, a coalition of indigenous campaigners, environmental activists, craw fishermen, and local St James residents are pooling their resources and expertise, and are at the forefront of a growing grassroots movement in Louisiana. Water Protectors, including Cherri Foytlin who runs BOLD Louisiana, refer to the proposed pipeline as ‘the two headed black snake’, and anti-pipeline protestors are forming protest camps, adapting techniques witnessed at Standing Rock.

Despite assurances from Energy Transfer Partners that they ‘will incorporate state of the art protection systems’ and monitor the pipeline around the clock, concerned environmental activists believe the drinking water of thousands of people in south Louisiana will be put at risk by the pipeline. Activists also point to the erosion of sensitive wetland ecosystems, such as the Atchafalaya Basin, which is already crisscrossed with pipelines and manmade spoil banks that can halt the natural flow of water. This growing environmental coalition of citizens regularly protests at the State Capital Building in Baton Rouge, petitioning Governor John Bel Edwards to produce an Environmental Impact Statement.

For many people in Freetown and the wider Fifth District of St James Parish, this pipeline is the last straw. Many feel inundated by industrial expansion: ‘Its like we are surrounded…’ explained one resident during a focus group, ‘we are penned in on all sides!’ Having spent time with this community, it is easy to see why people are frustrated. Unlike other toxic places I have researched, such as nuclear landscapes in Fukushima and Chernobyl, where contamination is beyond the reach of human senses, here the pollution is vivid, thick, and profoundly palpable. It gets caught in your nose and throat, and can make your eyes run and your skin sore. It is odorous and invasive, entering homes at night when the air becomes thick with petrochemical trespass. It is also present in the stories of illness that people share.

Interviewees described a spectrum of attritional health complaints, from headaches, skin irritations, sinus infections, dizziness and rashes, to reported increases in cancers and other terminal illnesses. ‘Everyone round here knows someone with cancer’, explained Catlynne*, who lives near Freetown in the fenceline community of Burton Lane. In the neighboring Parish of St John, the Environmental Protection Agency have recently declared it the highest risk in the country for developing cancer, from 5 to 20 times higher. But it is not just death and cancer that defines the lived experience of pollution. As I sat on Catlynne’s veranda, overlooking giant storage tanks on the other side the fence, she pointed to the various trees and plants in her garden, which she said would no longer grow. ‘It’s the air’, she explained.

Interviewees described a spectrum of attritional health complaints, from headaches, skin irritations, sinus infections, dizziness and rashes, to reported increases in cancers.

Plantations and chemical plants share a divisive and ongoing history, each one reproducing its own kind of attritional violence. Curiously, the words ‘plant’, ‘plantation’, and ‘chemical plant’ share an etymological link: they stem from the old-English word [plante] for something you ‘put in the ground to grow’ and the Latin [plantare], meaning ‘to fix in place’. Fittingly, with each new petrochemical facility that gets approved in Louisiana, a ‘groundbreaking ceremony’ takes place. Local dignitaries, politicians, business insiders and the press are invited to assemble around piles of carefully placed dirt. Golden shovels, often tied with celebratory ribbons are used, as businessmen pose for cameras and act out the ritual of ‘planting’. It’s a symbolic act: digging the soil and planting a new petrochemical future. The methanol plant currently being constructed just south of Freetown received this ritualistic treatment in 2015 (see photo), and the proposed Bayou Bridge Pipeline – if it gets the go ahead – will doubtless receive the same corporate performance. For the community in Freetown however, who are attuned to their own soil, plants, and environment, another image comes to mind. As the petrochemical assemblage of pipelines, storage tanks and chemical plants continue to grow near Freetown, the plant life here may also continue to die.

*some participants names have been changed to protect identities

References:

Bullard, R.D., 1990. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. Westview Press.

Carson, R., 1962. Silent spring. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Davies, T. and Polese, A., 2015. Informality and survival in Ukraine’s nuclear landscape: living with the risks of Chernobyl. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 6(1), pp.34-45.

Davies, T., 2018. Toxic space and time: Slow violence, necropolitics, and petrochemical pollution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(6), pp.1537-1553.

Davies, T., 2019. Slow violence and toxic geographies:‘Out of sight’ to whom? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space,

Fanon F, 1963. The Wretched of the Earth translated by C Farrington (Grove Press, New York).

Nixon, R., 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.

Zimring, C.A., 2017. Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States. NYU Press.