Angelo Raffaele Ippolito (United Nations University – International Institute for Global Health)

Bruno Andreas Walther (National Sun Yat-Sen University)

Between 2017 and 2018, I carried out ethnographic fieldwork in the Southern Italian city of Taranto. Being from the city myself, I was aware of the ongoing struggle between a small group of active citizens and the largest steel mill in Europe, Ilva (formerly Italsider), which since the 1960s has completely transformed the economy of the city whilst also bringing illness and death to its people.

The efforts of a few activists in the late 2000s have led to one of the largest trials for environmental disaster in Italy, increasing the visibility of Taranto within Italian politics and calling for institutional action. Despite this leap toward environmental justice, there was something that simultaneously interested me as a researcher and frustrated me as a Tarantino. The environmentalist movement in Taranto became prominent only in the late 2000s, but the factory had been operating since the early 1960s. Even considering the recent environmentalist ‘victories’, the majority of the population in Taranto seemed to be largely disengaged from the environmentalist movement. On 14 April 2013, the people of Taranto were called to vote in a referendum on Ilva’s closure. Among the 173000 people eligible to vote, only 19.6% casted their vote. By failing to reach the 50% minimum quota imposed by Italian law, the outcome of the referendum was nullified.

While a partial explanation of Taranto’s environmentalist apathy lies in the dependency of the community on the jobs provided by the industry, I suspected that there are also wider historical and sociocultural structures that have prevented the community from taking action. What I found during my research is a community which seems to have largely resigned its willingness to fight for political change. However, some people have initiated a process of critical understanding of their own role within the political context they inhabit. This might constitute a different form of resistance which I will elaborate upon below.

The Steel Planet

Let me first share two illuminating examples of how the factory and the associated narrative of industrialization have profoundly affected the shared moral vocabulary of the community. While these examples are not sufficient to explain the lack of public engagement with the environmentalist movement, they nevertheless serve as a reminder that the moral dimension of the community has also been polluted by the ideology which accompanied industrialization.

Il Pianeta Acciaio (1962). SOURCE: Fondazione Ansaldo

The powerful imagery of olive trees being ploughed down by bulldozers to make space for Ilva’s industrial complex were made by Italian novelist Dino Buzzati in the short film documentary Il Pianeta Acciaio (1962 – The Steel Planet). This film was produced one year after the inauguration of the factory and described it as a source of economic and moral salvation for the people of Taranto, who had prior to its construction been condemned to civil and economic backwardness. The images and text stressed the notion of the community being not only economically, but somehow also morally inferior to the rest of modern Italy. Thus, in the midst of the merciless eradication of nature, the overbearing rise of giant factories, and the acclaimed construction of modern roads and homes, a new set of desires was also being fabricated for the community of Taranto. In the documentary, a voice-over describes the birth of the factory:

“Away the olive trees, away the old little houses, away the cicadas and the ancient Mediterranean enchantment. The bestial machines want to turn everything into a desert, a flat land without a blade of grass. A few hours are enough to erase thousands of years, and now the beasts [the bulldozers] keep on paving the soil. Why did they do so? Because the olive trees, the sun, the cicadas meant sleep, abandonment, resignation and misery. And now, instead, men have built this huge cathedral of steel and glass so that it can become home to the fire monster which is known by the name of ‘steel,’ which also means ‘life’.

We are near Taranto, this is the new Italsider citadel, and one day it will become even bigger than Taranto itself. It’s a metallic skeleton, and already produces giant steel tubes. In it, thousands of workers will find a stable job, tranquility and pride. Hundreds of them already work here, they came from the land, the pasture, the resignation. Today, they already think of themselves as different men, they feel alive and modern, they no longer feel a sense of shame or envy when they see the big trucks coming from Genoa and Milan driven by those Northerners and their industrial faces. Now they think of themselves as equals to them, with the same strengths and the same capabilities…”

Il Pianeta Acciaio – 1962

Taranto’s longing for modernity implied a revolution not only in the economic and social dynamics of the community, but also had deep effects on the very way its people perceived what really matters – what Kleinman (2008) would refer to as their local moral world. This superimposed narrative of the benefits of industrialized growth was internalized by the people who started to feel a need for the factory as a means to move forward. Becoming modern also required a profound cut with the agricultural past of the community, which acquired an inferior moral collocation. One of my informants recalled her husband’s satisfaction with his job at the factory, which “gave him an identity.”

The film documentary constitutes a distilled historical testimony of the extent to which the people of Taranto had to give up their own past in order to pursue modernity. It shows how the factory not only represents a material reality, but also stands as a powerful symbolic assemblage shaping the moral world of the community. Over time, the moral configuration of the community transformed according to the economic, sociocultural and political shifts in Taranto. Today, the community’s morality shaped by the 1960s industrialization and its economic success clashes with the experience and information about illness and death in the city[1]. For this reason, the factory has been acquiring new symbolic connotations, now also embodying the struggle of the people of Taranto and their inability to voice their suffering.

Jesus Heavenly Worker

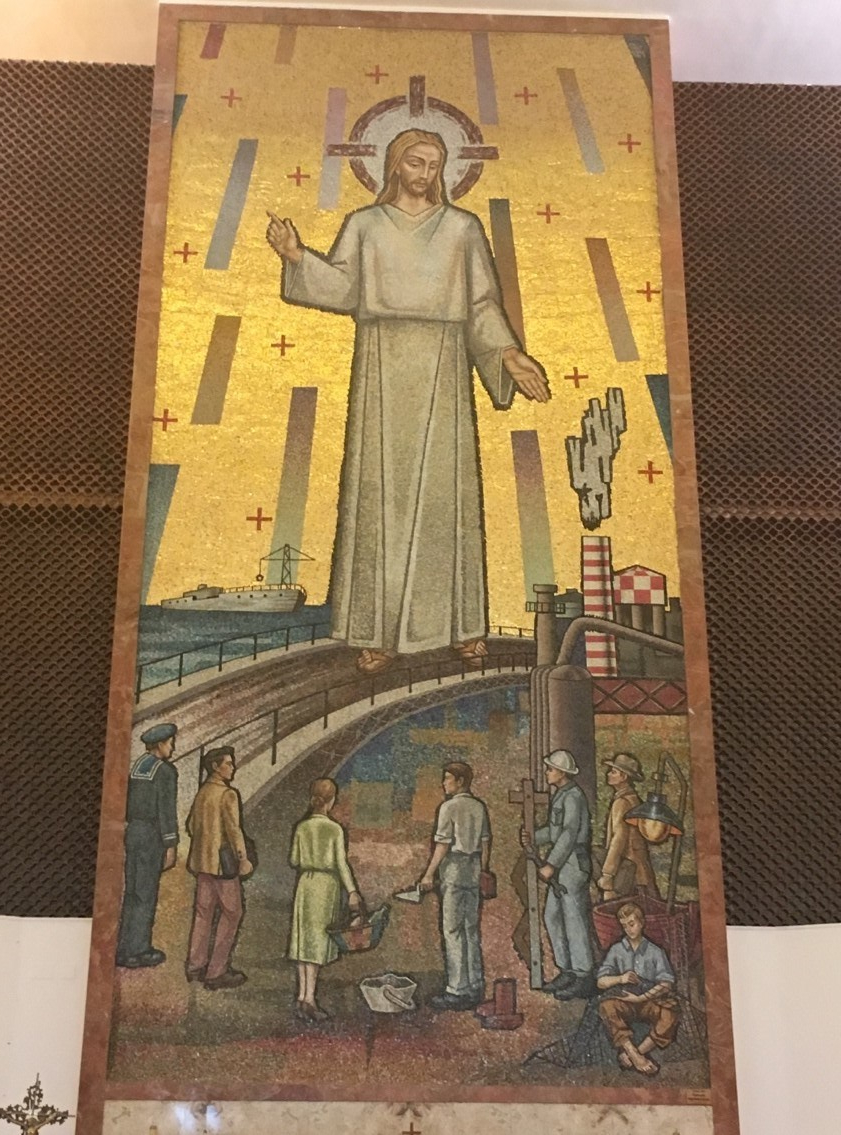

The second powerful image which exemplifies the moral world shifted by industrialization is found in the Parish Church named Gesù Divin Lavoratore (Jesus Heavenly Worker) which stands a few hundred meters from Ilva’s chimneys. Located in one of the most critically polluted districts of the city, the church constitutes a place for the gathering of the community. Above the white altar, there is a large mosaic that dates back to 1977-8. It portrays Jesus standing on the Ponte Girevole (the Swing Bridge), which was built in 1958, and constituted a milestone in the city’s structural development. The bridge connects Taranto’s factory to its people and their modern occupations: depicted are a navy officer, an engineer, a housewife, a construction worker, a factory worker, and an architect. They all stand facing the factory and the Son of God, looking toward their future, except for one of them, who is sitting down and directs his sight toward the observer. The fisherman is barefoot, and his clothes are not as neat as those of the people standing up. Segregated in the bottom left corner of the mosaic, he is meant not to look forward and thus is excluded from the modern future that awaits the others. Jesus points at the factory and at the sky, reminding the community that the industry is a gift from the Divine Providence, a means through which the community can finally rewrite their destiny of tradition and poverty and become modern. Jesus’ hands also serve as a reminder that it is through hard work and dedication that the community can enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

One day, as I was chatting with a worker about that mosaic, he said: “that piece of art is quite ironic. Forty years ago, people were sure that what Jesus meant by pointing at the factory and the sky was that, through hard work, people can have the privilege of going to Heaven. But now we know the truth. What he really meant was to be careful, because if you work at the factory you’re going to end up going to Heaven sooner than you should!” Retrospectively, the consideration of the man still makes me smile, but it is also the perfect exemplification of how shifting moral understandings of the world produce significantly different interpretations of the same material reality, redefining the preexistent beliefs, economic conditions, and interdependences over time.

To me, the mosaic is more than a religious decoration; it rather constitutes a temporal window onto the moral world of the 1960-70s; it is a symbolic arena in which the community can reflect on the past world and create new understandings of their reality. A priest of the church used the figure of Jesus in the mosaic to critique Taranto’s ideals of work in the 1970s:

“Now let me tell you something from a historical perspective and not from a religious one. I am talking about historical coherence and therefore about the fact that Jesus of Nazareth has worked until the age of 30, he was a real worker. This church was born in the 1960s when in the Catholic Church there wasn’t yet a lot of movement, hence they had the idea that Jesus should be represented wearing a white vest and with his hands open, without a single callus on his fingers. [Thus, in the mosaic,] It looks like he’s never worked in his life. […] therefore we can say that that mosaic represents the mentality and the culture of those years, a moment in which Jesus was seen as the Son of God and not as the Son of man. For the Catholics, Jesus is True God and True Man, but there isn’t much of a real God in that mosaic…”

Aside from the religious relevance of his personal view, the priest’s critique encapsulates the moral transformation that the community has undergone in the last sixty years. First, it expresses a general hostility and antagonism towards a 1960s mindset avidly pursuing industrialization but still driven by traditional and backward morals. In the mosaic, the image of Jesus Heavenly Worker dressed in a white and spotless vest is a strong signifier of the social prominence of the workers and their occupation in the project of industrial development of the late 1900s. The ideal worker (represented by Jesus) utilizes hard work and sacrifice in order to gain access to Heaven, which here also stands for social recognition.

On the other hand, the priest’s contemporary portrayal of Jesus defines a humbler identity for the workers (and therefore Jesus), stressing on the acceptance of suffering as a destiny that is not necessarily rewarded in an afterlife, but that defines the very essence of the human experience. This view is shared within the community, and reflects the current attitudes of the workers toward the pollution produced by the factory, namely a propensity toward enduring suffering rather than protesting it. Furthermore, according to most workers interviewed, the old mindset is also to be deemed accountable for today’s degradation of Taranto’s economy and its environmental destruction.

“The factory is within you”

The two visual examples proposed above are ways through which the factory intrudes the subtleties of the social and moral life of the community and shapes their understanding of the world. One worker encapsulated this in the sentence “the factory is within you”, deeply affecting the very way individuals think and feel in Taranto. Ilva is therefore responsible not only for the physical degradation of the community, but also for a moral struggle that has divided its people over two generations, and that is partly connected to their inability to participate in the environmentalist movement.

At the same time, the community’s propensity toward self-reflexivity and the contemplation of the past described above echoes Lora-Wainwright’s (2017) notion of resigned activism, namely ways of remediating pollution that do not fall in the immediate spectrum of activist resistance, but that unveil the moral struggle of living in a contaminated world. This dimension needs to be acknowledged in order to reform our understanding of environmental justice in Taranto. Rather than promoting the participation of the public into predetermined forms of resistance, the focus should be on expanding the environmentalist movement into the moral struggle of the community. This requires restructuring the activist and political agendas, going beyond pollution and reflecting upon the incommensurability of environmental loss (Centemeri 2013), realizing that the spaces to be reclaimed are physical as much as moral.

All photos credit: Fausto D’Alessandro