Sarah Marie Wiebe (University of Hawai’i, Mānoa)

Jen Bagelman (University of Exeter, United Kingdom)

Laurence Butet-Roch (Ryerson University)

I didn’t Know!

Poem by Ada Lockridge

Aamjiwnaang First NationI didn’t Know that we had

a say on what goes on in the plantsI didn’t Know what was being released or how

much or the Known health effects from it.I didn’t Know to call MOE Spills Action Hotline to report any

unusual smells or happenings

and to ask for a copy of the

incident report.I didn’t Know that when

there is a evacuation that

I should check the wind

direction and Know which

plant it is so I can take

the safest route away.

(Do not drive with wind blowing

At you.)I didn’t Know that it wasn’t safe to swim or play in

the St. Clair river or

the ponds here, or ditchesI didn’t Know it wasn’t

safe to eat the fish or

the deer or rabbits here.I didn’t Know that I

should keep my windows

closed at night since the

plants mostly burn from

the stacks at night so as

to not bother so many

or something like that.I didn’t Know which government

is responsible for what,

still a bit ify on that too.

Chief & council, Sarnia Mayor, St. Clair

Township, Municipalities, Counties,

Provincial, Federal, Health Canada,

Environment Canada, Dept. of Oceans and

Fisheries, Indian Affairs, Ministry

of Environment, M.P., M.P.P.,

Ministry of Natural Resources.I didn’t Know that those

flares should only be

burning when there is

a problem.I didn’t Know that workers

get some kind of a slip when

they have been exposed to

chemicals?I didn’t Know how hard it

is to collect pensions?

for the widows or disabled

workers.I didn’t Know that when

there is a power outage

why we get our power back

on so fast. (we are in more

danger when the plants don’t

have power)I didn’t Know that the

colors burning off the flares

mean different substances are

burning off.I didn’t Know that those

beautiful colors of our

sunrise and sunsets are due

to pollution & chemicals.I didn’t Know that it is

best to take water samples

after the cities routine

flushing. (And make sure they

are testing for heavy metals)I didn’t Know that the watermain

on S. Vidal is ours but the

city maintains it. It is over

60 yrs old and made out of cast iron.I didn’t know that when

Suncor was building their

1st flarestack that they

were digging up human

remains. ( I don’t Know

What they did with them)I didn’t Know that these

Chemicals are used to

make plastics, tubes in

hospitals, make up, batteries,

carpets, cooking pans, nonstick

cleaning products.I didn’t Know the same

companies here make the medicine for cancers and

other ailments.I didn’t Know that there were

noise and vibration laws

for these plantsI didn’t Know that some

plants have a native

hiring policyI didn’t know the plants

Had native liaison reps.I didn’t Know they (plants) can

do pollution credits sharing

or selling (since they are allowed

to release so much into the air?)I didn’t Know we sold the

land so that industry could

come, so that people would

come to the area and

create jobs (what was Known about

chemicals then?)I didn’t Know that when

the gov. had Indian Agents

here supposedly taking care

of us, that we were not

allowed to have legal

representation.I didn’t Know that there

was a statistic that there

should be 51% boys to 49%

girl ratio worldwide.I didn’t Know anything

about accumulative effects

(I couldn’t even say it till now, 2010)I didn’t Know that these

Chemicals here can be

passed on through generations.I didn’t Know that existing

air monitors aren’t set up

to collect all samples that

could be out there.I didn’t Know that when there

is a release that you need to

know what it is first so they

know what kind of reading instrument

to use.I didn’t Know that the

workers are scared to

report things fearing loss

of job.I didn’t Know that workers

have reported maintenance

problems and they don’t

get fixed until they blowI didn’t Know that routine

maintenance checks on

holding tanks are only

every 10 yrs.I didn’t Know that the

riveted holding tanks

are out of date.I didn’t know that these

industries are still using

some machinery from when

they first came.I didn’t Know that there is

a new law about pipelines

being too close to homesI didn’t Know when the

plants get fined that it

goes to the municipalities.I didn’t Know that the

plants have to give out

1% of its profits to

the surrounding communitiesI didn’t Know that people

in a 1 mile radius of

Clean Harbours receive a

yrly “fee”I didn’t Know there was

such a thing as a

long term health based

standardI didn’t Know that there

is no standards here

for some of these known

carcinogens (these will cause cancers)I didn’t Know that Lanexss

supplies the rubber that

is in gum (I thought rubber tires)I didn’t Know that the city of

Sarnia police don’t have money

in the budget to buy the

proper gear for when there

is road blocks due to

chemical releasesI didn’t Know that when

Industry wants to change

any of their operations or

to add to it, they have

to post it on the EBR

website (Environmental Bill of Rights)

and anyone has 30 days

to comment on it.I didn’t Know that the

gov. works by the four D’s

Deny, Delay, Divide,

Discredit

oh and maybe throw in a

“study”I didn’t Know that

medical doctors are

not trained on how

these chemicals react

to the human bodyI didn’t Know that we

probably need: oncologist,

Epidemiologist, toxicologist,

Meteorologist, pathologist.

Dirty Stories, Toxic Bodies

Along the St. Clair River at the southern tip of Lake Huron, in the heart of the Great Lakes, Canada’s ‘Chemical Valley’ – a toxic petrochemical complex – occupies Aamjiwnaang Indigenous territory. Approximately 2,000 Anishinabek people call this their home, which is now reduced to a small reserve due to land dealings enabled by public officials at multiple levels of government over the years. Stretching over 30 km, their territory houses the largest concentration of petroleum and chemical industry sites in Canada.

This toxic geography did not emerge by accident. Resource extraction in these territories began in the mid-19th century and in 1858, oil was first discovered in this region. From the discovery of gum beds in the Enniskillen Township in 1851, to the birth of the Chemical Valley in the 1940s with the expansion of Polymer Corporation following the Second World War, the power of industrial development has deep roots. Aamjiwnaang is entangled in wider processes of ongoing colonialism and neoliberalism. To this day, the extraction industry continues to envelop the Aamjiwnaang First Nation reserve.

In 2005, Ada Lockridge – an Indigenous mother, activist and citizen of the Band and former Council member – teamed up with researchers and discovered that for every two female births in her community, only one male was being born. This study triggered alarm across multiple scales of government: local, provincial and federal. While the 2005 study could not conclusively attribute the community’s toxic exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, the federal ministry of Health Canada encouraged the formation of the Lambton Community Health Study. The Lambton County health department produced their own reproductive health report in 2007, which showed no abnormal birth patterns when scaled away from the Aamjiwnaang reserve to the county, a wider population of approximately 120,000 residents.

In addition to the abnormal birth ratio, over the years, Aamjiwnaang residents also expressed concern about high levels of autism, asthma, cardiovascular disease, miscarriages and cancer. These unique, site-specific concerns were not documented or addressed by the Lambton Community Health Study, which dilutes the Indigenous community’s lived-experience and eclipses the colonial and neoliberal processes that constitute Aamjiwnaang as a toxic space. Official representations of the community, apparent in media accounts and public statements from external decision-makers, further obscure the ways in which the community actively contests these processes. Our main focus is not to simply problematize this limited representation but to instead call for a more multi-dimensional, prismatic account of Aamjiwnaang’s everyday exposure to toxins and practices of resistance. Such a prismatic lens draws into focus multiple angles: academic, artistic, photo-journalistic and poetic.

Reframing the Geopolitics of Pollution: A Prismatic Lens

To glean insight into, and shed light on the complexities of Aamjiwnaang’s lived-experiences, we offer a close reading of this site through Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia. A heterotopic analysis examines ‘other than’ spaces through multiple lenses to understand complex spaces and processes, and prompts viewers to look beyond the state to understand the inner workings of power, written onto the bodies of affected parties. The heterotopia rejects simplified dualisms and narrow narratives of victimhood. Instead, it offers a useful lens to deepen an understanding of multiplicity and contradiction. Such a prismatic approach allows us to trace the ways in which certain sites are simultaneously cloaked in darkness and left exposed. A prism serves to cast light upon the political ramifications that emerge due to this political spectrum of exposure.

While Foucault’s approach is helpful, we argue that it is inadequate in illuminating the fulsome ways in which toxicity is intimately experienced, felt, and resisted. Drawing on Indigenous academics and activists, such as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Ada Lockridge, as well as feminist geographers, such as Rachel Pain, we argue that it is vital to dig deeper to unearth the lived realities of places rendered exposed, such as Chemical Valley. To do so, it is vital to become attuned to the everyday environmental injustices that constitute life in Aamjiwnaang which are too often invisibilized. Such an approach requires paying greater attention to the knowledges and situated stories articulated by community members which reveal various forms of, often slow, violence and also sustained acts of resistance. These knowledges are not confined to policy documents or even written accounts but range from documentary films, to rap music, dance and poetry. It is in the spirit of making greater space for these dynamic poetic knowledges that we begin this piece with the stirring words of Indigenous activist and poet, Ada Lockridge. For this poetic work refuses to let us forget the smells, tastes, and sights that comprise a toxic body politics. It refuses for us to put aside, for instance, the polluted fish and sunsets that give rise to alarming cancer rates. Instead, Lockridge’s work emplaces the reader squarely, and somewhat uncomfortably, in a toxic environment where — for a change — forms of colonial ‘care’ are made palpable and left exposed.

Additional Resources

Bagelman, Jennifer and Sarah Marie Wiebe (2017). “Intimacies of global toxins: exposure and resistance in Chemical Valley”, Political Geography. 60(76-85).

Butet-Roch, Laurence. Our Grandfathers Were Chiefs. https://www.lbrphoto.ca/PHOTOS/Our-Grandfathers-Were-Chiefs/1.

Craig et al. (October 2017). “There are toxic secrets in Canada’s Chemical Valley”, National Observer. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2017/10/14/news/there-are-toxic-secrets-canadas-chemical-valley.

Hoover et al (2012). ”Indigenous Peoples of North America: Environmental Exposures and Reproductive Justice”, Environmental Health Perspectives. https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.1205422.

Kiijig Collective (2012). Indian Givers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pot411GJzdM

Mackenzie, Constanze, Ada Lockridge and Margaret Keith (2005). “Declining Sex Ratio in a First Nation Community”. 113(10): 1295-1295. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1281269/

Pain, Rachel (2019). Chronic urban trauma: The slow violence of housing dispossession. Urban Studies

Simpson, Leanne (2013). Islands of decolonial love. Winnipeg, MB: Arbeiter Ring Publishing.

Wiebe, Sarah Marie (2016). Everyday Exposure: Indigenous Mobilization and Environmental Justice in Canada’s Chemical Valley. Vancouver: UBC Press.

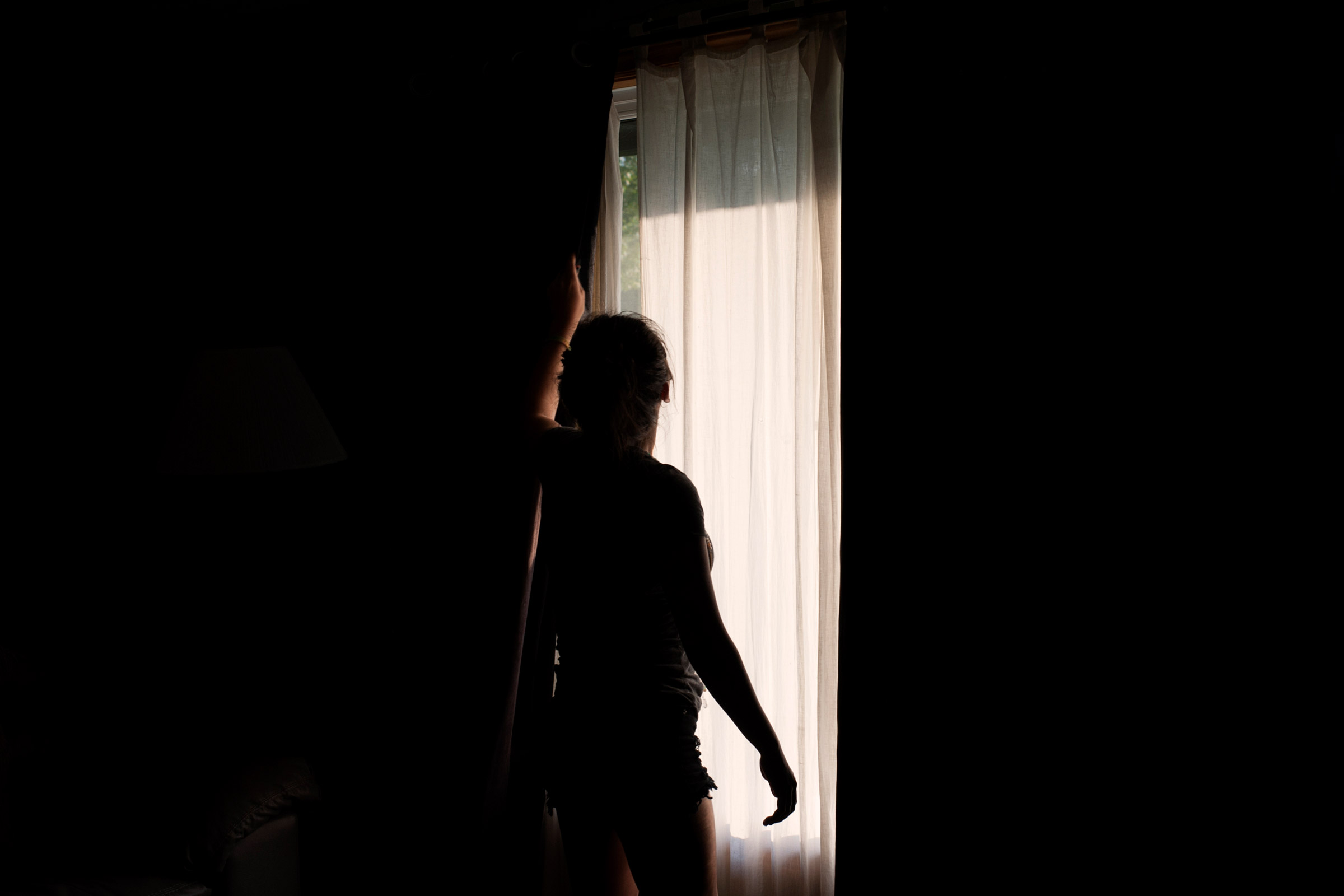

Photos from the series Our Grandfathers Were Chiefs (2010-2018) by Laurence Butet-Roch

01

02

03

04

05

06

07