Becky Alexis-Martin explores the materiality of the nuclear industry in a multi-sited photo-essay

Dr Becky Alexis-Martin, Senior Research Fellow in Human Geography at The University of Southampton. @MysteriousDrBex

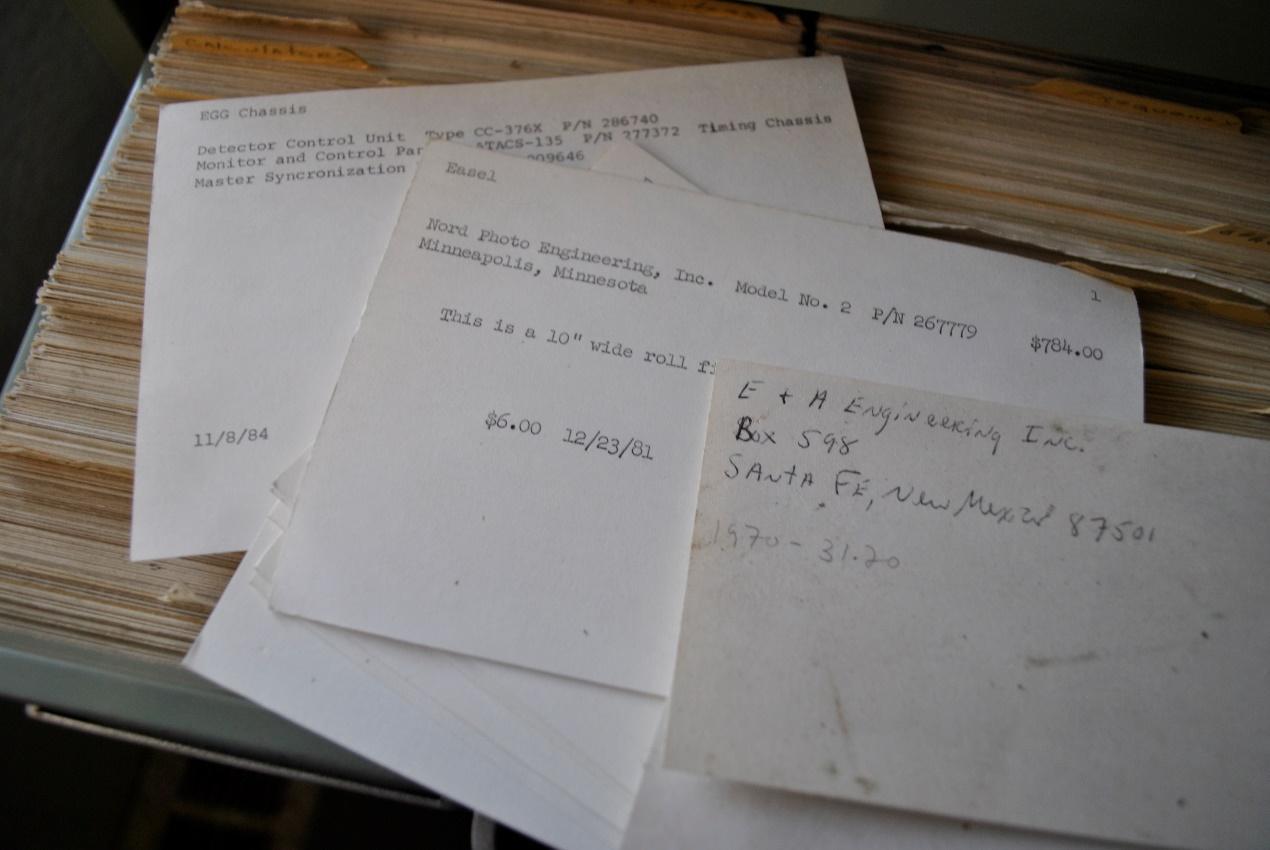

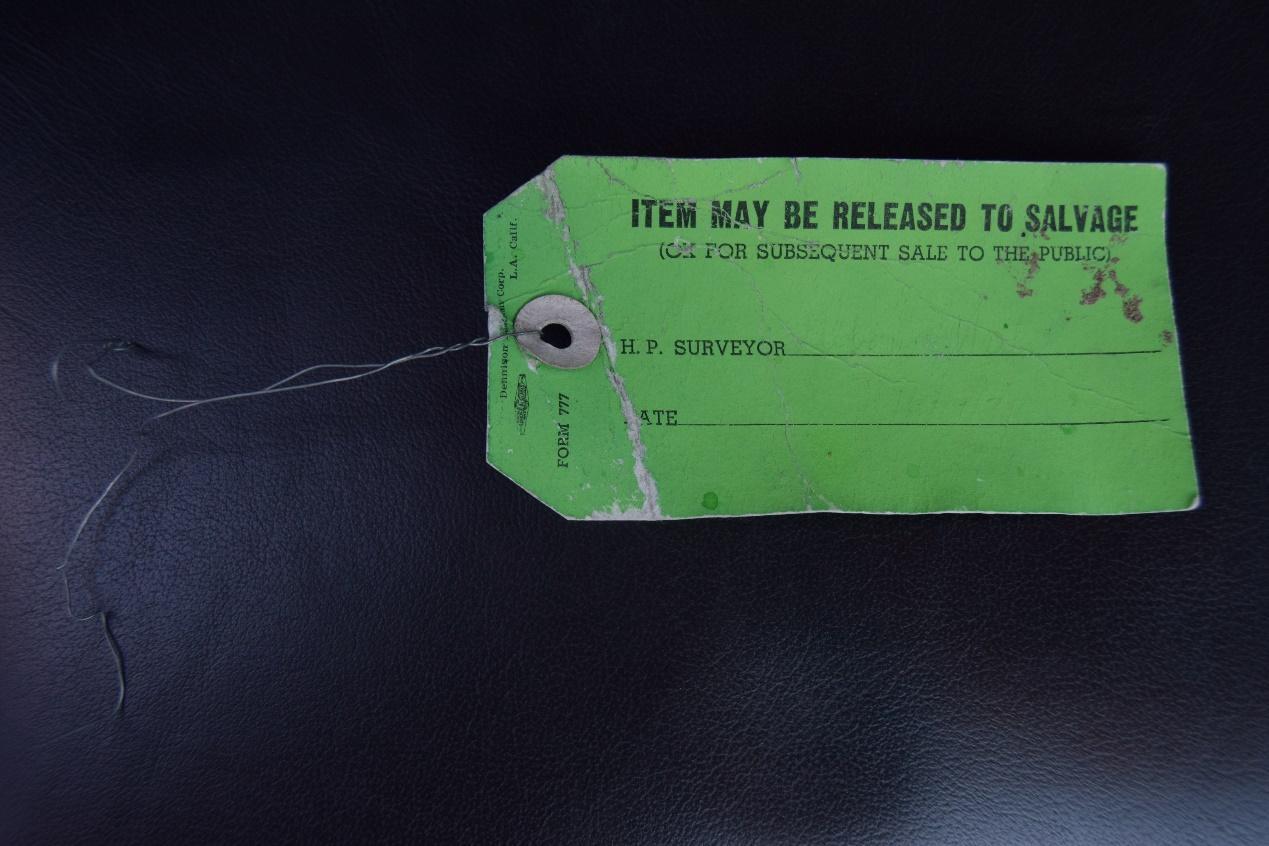

A layer of detritus festoons every abandoned filing cabinet and empty shelf. The fierce midday sun pierces the hazy windows, causing suspended motes to shimmer in the dustbeams, and cast long shadows across the concrete floor. This place once stored and sold some of the discarded scientific equipment from Los Alamos Nuclear Laboratory, serving as a para-nuclear waste repository for useable junk,¹ originally created by the American nuclear military industrial establishment. Now, the most interesting scientific artefacts are long-gone from the Black Hole of Los Alamos, and all that remains is a derelict husk of a building.

On the other side of the world, misplaced bunkers squat on chalky concrete foundations. Ochre-streaked paint disintegrates to reveal scaly blisters of rust. The nearby officer’s mess has already had several afterlives, and is now in a state of advanced decay, repurposed as a makeshift home by some local families. The military church is uninhabited and its cobblestone architecture is gradually succumbing to nature. Kiritimati is an abject place,² still scattered with relics of the nuclear imperialism that occurred during the 1950s and 1960s. Considerable mythopoesis surrounds the H-bomb tests undertaken here by the USA and UK, and veterans tell stories of x-ray hands and savage sting rays.³ The island retains its dark nuclear heritage, and is visually polluted by the material remnants of its past.

“Para-nuclear waste is not radioactive itself, but is an incidental by-product of the nuclear military industrial complex”

Para-nuclear waste is the inert waste that has been created alongside radioactive waste. It is not radioactive itself, but is an incidental by-product of the nuclear military industrial complex. Para-nuclear waste has a physical presence, a materiality that ionising radiation lacks. Instead, it emits ostranenie.⁴ It is out-of-place yet still familiar, having transcended its original purpose. It is the rusting filaments of defunct laboratory apparatus, the cracked lime concrete of abandoned military building foundations, the deserted cabinets stuffed with obsolete secrets. The narrative of para-nuclear waste is therefore constructed of mysterious endings and abandonments. It is often unmanaged and unruly. It may end up in landfill or a school science laboratory. It may be sold off, given away to the local community, or even left to decay in-situ for decades.

This photo essay includes incidental images that I have accumulated from 2016 to 2018, during fieldwork in New Mexico, USA and Kiritimati in the South Pacific. Los Alamos National Laboratory was the birthplace of the first American atomic bomb in 1945, and still functions as a nuclear weapon laboratory to this day. Kiritimati was occupied by the UK and USA during a series of nuclear weapons tests from 1957 to 1963. It gained independence in 1979, but still experiences developmental and environmental challenges that are linked to its colonial past. The purpose of this photo essay is to gently explore the diverse aspects of unmanaged para-nuclear waste, from the creation to the detonation of the atomic bomb.⁵

Becky Alexis-Martin is a Senior Research Fellow in Human Geography at the University of Southampton. Her research interests are focused around the human experiences of the international nuclear community. She has a forthcoming book on her nuclear research with Pluto Press. Check out her recent Geography Compass article on ‘Nuclear Geography‘ here.

Other articles in this Special Issue:

- Editorial: Toxic Visions – Photography and Pollution

- Exposing a Chemical Company

- The Red Forest: Picturing Radiation with Infrared Film

- Disposable Citizens: viewing Chernobyl through the lens of those live there

- The derelict afterlives of para-nuclear waste

- Rare Earthenware: photography, pottery, and pollution

- Graveyard of Giants: the Toxic Afterlives of Ships

- Treasure: Landscapes of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve

- Voyage on the planet: contemplating pollution with Chih Chiu

- Toxic Expertise Annual Workshop 2018

Footnotes and References

- Para-nuclear waste is used here as a way to describe the nuclear connections of non-radioactive waste from the nuclear military industrial establishment.

- By abject, I mean a disturbance in the state of affairs by the presence of matter being out of place. In this scenario, the abandoned para-nuclear waste and remnants of nuclear imperialism on the island of Kiritimati provoke a sense of the abject.

- Oulton, W.E., 1987. Christmas Island cracker: an account of the planning and execution of the British thermo-nuclear bomb tests, 1957. Thomas Harmsworth Publishing.

- Ostranenie (остранение) is used here to refer to the way that para-nuclear waste objects become defamiliarised beyond of the setting of the nuclear military industrial complex. Please see Shklovsky, Art as technique [1917]. Berlina, A., 2018. “Let Us Return Ostranenie to Its Functional Role” On Some Lesser-Known Writings of Viktor Shklovsky. Common Knowledge, 24(1), pp.8-25.

- Peeples J. Toxic sublime: Imaging contaminated landscapes. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture. 2011 Dec 1;5(4):373-92.