Dr Thom Davies, Research Fellow at the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick @ThomDavies

Many documentary photography projects attempt to reveal the structural violence that society has wrought. Monsanto: a photographic investigation by photographer Mathieu Asselin is more specific in its aim: it is a visual call for corporate responsibility. Drawing on the theme of temporality that pollution often creates, the photobook is a timeline that documents over 100 years of chemical harm. The book explains through word and image how the agrochemical company Monsanto has caused ecological, social, and health problems for countless people across the world.

“The book draws on a wide range of visual techniques to tell its dark story”

If Asselin’s visual project was an academic dissertation, it could be described as using a ‘mixed methods’ approach. I don’t make the comparison to scholarly work lightly: the photobook is an impressively well researched photo-thesis. It could also be compared to recent moves within academia towards ‘slow scholarship’: the photobook is the product of long term investigative documentary work. From studio photographs, to outside portraits, and from candid images, to landscape photographs, the book draws on a wide range of visual techniques to tell its dark story.

It is both ethnographic and archival in tone, weaving original images with repurposed corporate texts and pictures. As Colin Pantall rightly said: ‘it punches home a message by any means necessary’. The book is both sophisticated and thorough, providing a well timed antidote to the Greenwashing that chemical companies so often employ. It is no surprise that a company like Monsanto does everything it can to improve its reputation, as accusations of environmental injustice still abound: in June this year the company will go on trial for allegedly hiding evidence that their weed killing products cause cancer.

Monsanto: a photographic investigation extends the conventional borders of documentary photography, using documents, memorabilia, advertisements, and found objects in its narration of Monsanto. For example, the first ‘act’ of the book is dedicated to Monsanto adverts, which create a utopian image of the agrochemical company, which is later demolished through Asselin’s adroit visual material.

The juxtaposition between bullish slogans of Monsanto’s advertisements and Asselin’s careful documentation of the visual damage the company has caused is striking. ‘Chemicals make you eat better’ reads one corporate message; ‘Chemicals help you to live longer’ reads another. As Environmental activist Mark Lynas writes in ‘Seeds of Science‘, Monsanto tried and failed ‘to reclaim the word ‘chemical’ from rising public distrust and recast it as something good’. Asselin’s photography project becomes an interrogation, of sorts, exposing these messages for what they are. In one such official document displayed in the book, a memo from 1969 reads ‘we can’t afford to lose one dollar of business‘, raising questions about the uneven price of life, and what Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee calls ‘necrocapitalism’.

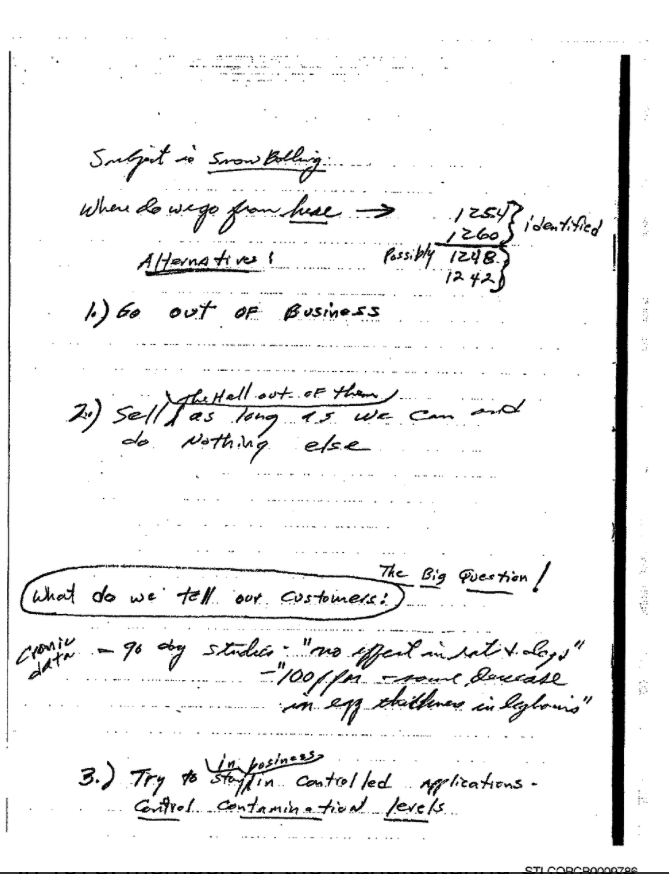

The academic project ‘ToxicDocs‘, from Columbia University and the City University of New York, recently unearthed classified Monsanto documents that demonstrate the necrocapitalism of the chemical industry. Among the millions of previously classified documents on industrial poisons that ToxicDocs have disclosed, are hand written notes from a meeting at Monsanto on 25th August 1969. The document reveals how the chemical company planned to deal with the harm that their PCBs’ were causing to the environment. At the meeting, they brainstormed several alternative ways forward, including “1) Go out of business“, and “2) sell the hell out of them as long as we can and do nothing else“. Monsanto would continue to sell PCBs for almost a decade longer, until public pressure helped to ban the chemical in the late 1970s.

“The book reminded me of ‘multi-sited ethnography’ that was made popular by British Sociologist Michael Burowoy”

Thematically, Monsanto: a photographic investigation can be compared to Philip Jones Griffiths’ monochrome photography book ‘Agent Orange: Collateral Damage in Vietnam’ (2003). Asselin, born two generations after Griffiths, not only exposes the intergenerational harm of this deadly defoliant chemical, but also traces the toxic reach of pollution back to the ‘unregulated paradise‘ of Alabama, USA. In this sense, the book reminded me of ‘multi-sited ethnography‘ that was made popular by British Sociologist Michael Burowoy, as well as the ‘follow the thing‘ approach forwarded by human geographer Ian Cook. The global connections and geographies of harm created by Monsanto are vividly portrayed in this photobook, in both photographic and extraphotographic ways.

HO CHI MINH CITY, VIET NAM, 2015. Photo credit: Mathieu Asselin

VAN BUREN, INDIANA, 2013. Photo credit: Mathieu Asselin

Like in other toxic geographies, at first glance the landscapes Asselin documents are not obviously contaminated, and the people he photographs are not always obviously affected. The photographs Asselin uses are shot in the places Monsanto touched with its social and chemical legacy, including Vietnam where many victims of Agent Orange still live, and the post-industrial landscapes of America, where other toxic legacies persist to this day. In the book we learn about Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) which Monsanto continued to manufacture for many years, despite knowing its health risks. We also learn how exposure to Agent Orange has been linked to myelomas, Parkinson’s disease, Hodgkin’s disease, lymphomas, Diabetes Type II, Leukemia, Amyloidosis, Prostate Cancer, and many other illnesses. In this photobook, Asselin exposes the chemical company to a visual scrutiny not normally given to powerful corporations like Monsanto.

“We are all living downstream of companies like Monsanto”

To quote the writer and photographer Lewis Bush: “It’s really, really rare that a photobook speaks to you in a way which feels important beyond the narrow realm of photography, and even does so in a way which feels desperately urgent.” (You can read his excellent review of the book and an interview with Mathieu Asselin here). Having spent the last few years doing ethnographic research with communities impacted by chemical pollution in ‘Cancer Alley’, Louisiana, I am also taken by the urgency of this subject. This photography project is not a work of historical retrospection, but an ongoing story that continues to impact the lives of many people around the world. We are all living downstream of companies such as Monsanto, and meticulously researched documentary work such as this photobook become important mechanisms to hold such industries accountable.

Mathieu Asselin is giving a talk about ‘Monsanto: a photographic investigation’ at Photobook Festival Kassel, Germany, on June 1st 2018: tickets here. You can follow Mathieu Asselin on twitter here. And find out more about his book here.

Other articles in this Special Issue:

- Editorial: Toxic Visions – Photography and Pollution

- The Red Forest: Picturing Radiation with Infrared Film

- Disposable Citizens: viewing Chernobyl through the lens of those live there

- The derelict afterlives of para-nuclear waste

- Rare Earthenware: photography, pottery, and pollution

- Graveyard of Giants: the Toxic Afterlives of Ships

- Treasure: Landscapes of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve

- Voyage on the planet: contemplating pollution with Chih Chiu

- Toxic Expertise Annual Workshop 2018

References:

Asselin, M., 2017. Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation, Verlag Kettler

Bobby Banerjee, S., 2008. Necrocapitalism. Organization Studies, 29(12), pp.1541-1563.

Cook, I., 2004. Follow the thing: Papaya. Antipode, 36(4), pp.642-664.

Griffiths, P.J., 2003. Agent Orange:” collateral Damage” in Viet Nam. Trolley

Lynas, M., 2018. Seeds of Science: Why We Got It So Wrong On GMOs. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nixon, R., 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.