In this Special Issue of Toxic News we explore different ways of making pollution visible:

Dr Thom Davies, Research Fellow at the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick @ThomDavies

The Hungarian photographer Robert Capa once said: ‘if your photographs are not good enough, you aren’t close enough’. He was a war photographer and famously captured the first images of the D-Day landings in 1944 in all their blurry, monochrome horror. Yet beyond the instantaneous violence of war, another brutality that continues to inspire, frustrate, and provoke photographers today, is the ‘slow violence’ of toxic pollution.

Conflict photographers have often held up a lens to pollution. W. Eugene Smith photographed Mercury poisoning in his striking work Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath; Philip Jones Griffiths revealed war’s toxic legacies in Agent Orange: Collateral Damage in Vietnam; and James Nachtwey made cough-inducing photographs of Indonesia’s noxious sulfur mines in the documentary ‘War Photographer’. Nachtwey is a five-time winner of the prestigious ‘Robert Capa Gold Medal’ for exceptional courage and enterprise. On his website, among the searing images of torn flesh and mourning mothers, is a section simply titled ‘Industrial pollution’.

In our epoch of drones, satellite images, and big data, we live in an age where getting close is not necessarily the best way to ‘see’. With toxic landscapes, Capa’s dictum is not so simple. How does one ‘get close’ to pollution, if its scale or very materiality is beyond our grasp? How do we visualise pollution that vibrates beyond the realm of our human senses, or is rendered invisible by the deferral of harm to future generations? These are all themes that the photographers and artists featured in this special issue of Toxic News have aimed to tackle.

“Photographing pollution is often a conversation with the invisible.”

Susan Sontag, a philosopher and famed critic of photography, wrote that ‘Today everything exists to end in a photograph’. If we are to take this quip seriously, then toxic landscapes certainly don’t make this process easy: simply put, photographing pollution is often a conversation with the invisible. From nuclear radiation, to microplastic pollution, often the worst threats we face are the hardest to render visible.

French photographer Mark Riboud, who made some remarkable pictures of China’s industrial landscapes in the 1950s – is often quoted as saying that ‘taking pictures is savoring life intensely every hundredth of a second.’ Yet there is an inherent tension between the quick temporality of photography and the slowly unfolding ‘moment’ of pollution. How can the neatly captured slices of time that photographs represent, do justice to the unendingness of toxic harm? As Susan Sontag poetically wrote in her book On Photography: ‘all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’. With ‘the Anthropocene’ presenting an apparently endless list of environmental problems, it seems not even ‘deep time’ will dissolve the long impacts of toxic pollution.

“The camera was born into a world of smokestacks and smog.”

In a sense, photography has walked step by step with industrial pollution since its invention in the early 19th century: the camera was born into a world of smokestacks and smog. Some of the very first images that the camera would have ‘seen’ were industrial landscapes. The first known photograph of a human being, for example, was made in Paris in 1838. The photographer, Louis Daguerre, made a ten minute exposure of a man having his shoes shined on Boulevard du Temple. Reading this image through the lens of the Anthropocene however, and it is not only the human that comes into focus, but the many chimney stacks that adorn each building: it’s not hard to imagine these stacks billowing coal smoke into the surrounding streets, along with the dawning of the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, had Daguerre pointed his camera West towards the Seine, he might have seen the many locomotive factories that once dotted the horizon, or the world’s first chemical plants that had been producing toxic substances (including nitric, hydrochloric, and sulphuric acid) in Paris since the 1770s.

Photography, then, is perhaps the talismanic tool of the Anthropocene – a technology to shine light onto our opaque and sublime environmental problems. As Sontag explained:

‘Cameras began duplicating the world at that moment when the human landscape started to undergo a vertiginous rate of change: while an untold number of forms of biological and social life are being destroyed in a brief span of time, a device is available to record what is disappearing’.

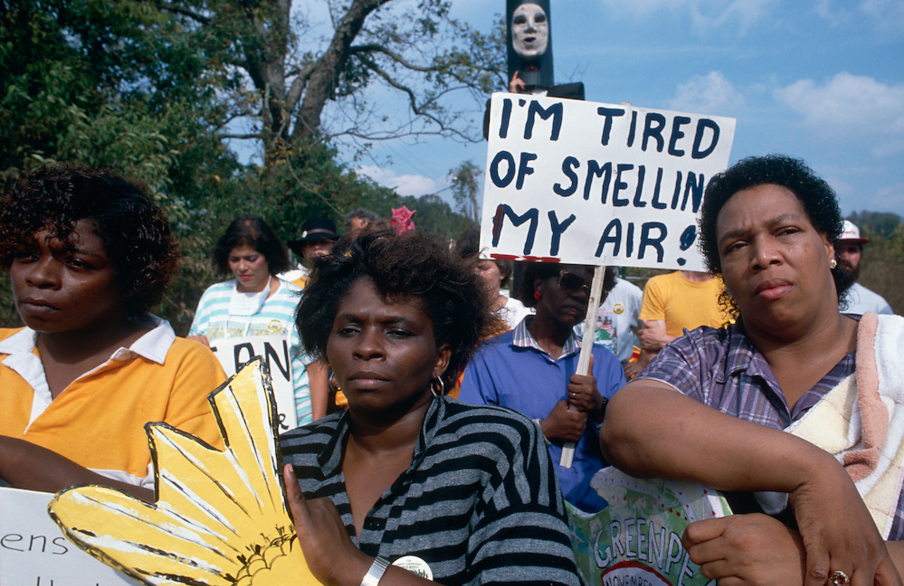

As others have noted, photography is not simply a mode of recording and documenting, but is also a vehicle of expression, art, and even activism. Photography has played a vital role in visualising environmental justice struggles. Photographer Sam Kittner, for example, photographed the Great Louisiana Toxic March in 1988 . He was mentored by photographer Declan Haun, who made important photographs of Civil Rights protests in the 1960s. Twenty years later, Kittner bore witness to the dawning of the environmental justice movement, photographing the toxic landscapes of ‘Cancer Alley’. His coverage of this period both capture the spectacular violence of pollution, as well as the quiet dignity of front-line activists, echoing the civil rights aesthetic of a generation earlier. Sadly, Kittmer’s photographs remain just as relevant today: thirty years after the Great Louisiana Toxics March, many of the same communities are still fighting environmental racism.

As environmental writer Rob Nixon warned, many forms of pollution are ‘resistant to dramatic packaging’. Photographers and artists have taken up this challenge, of finding innovative ways to narrate, translate, and make-visible the peculiar terror of pollution. ![]() For example, we are increasingly aware that plastic is a substance that the earth cannot digest. Several recent photography projects have dealt with the issue of plastic pollution in visually striking ways. Photographer Chris Jordan, for instance, takes up the theme of indigestion in his work ‘Midway: Message from the Gyre’. In a series of remarkable images, he documents birds on Midway Island in the Pacific who have died through consuming plastic waste. As he explains on his website: ‘The nesting chicks are fed lethal quantities of plastic by their parents, who mistake the floating trash for food as they forage over the vast polluted Pacific Ocean.’ His forensic-like images hold a macabre mirror to society, with each plastic-stuffed Albatross becoming a forewarning of our planet’s potential fate.

For example, we are increasingly aware that plastic is a substance that the earth cannot digest. Several recent photography projects have dealt with the issue of plastic pollution in visually striking ways. Photographer Chris Jordan, for instance, takes up the theme of indigestion in his work ‘Midway: Message from the Gyre’. In a series of remarkable images, he documents birds on Midway Island in the Pacific who have died through consuming plastic waste. As he explains on his website: ‘The nesting chicks are fed lethal quantities of plastic by their parents, who mistake the floating trash for food as they forage over the vast polluted Pacific Ocean.’ His forensic-like images hold a macabre mirror to society, with each plastic-stuffed Albatross becoming a forewarning of our planet’s potential fate.

The photographer Mandy Barker meanwhile takes a different approach to her work on maritime pollution. In her innovative projects Shoal, Soup, and Penalty, she focuses on discarded marine debris – the flotsam and jettison of the Anthropocene – and creates galaxy-like photographs of this ubiquitous plastic waste. Echoing ‘citizen science’ techniques developed within environmental justice movements, her project ‘Penalty’ was formed in a participatory way, involving 89 members of the public sending her footballs they had collected from across world’s shorelines. Hinting at the scale of this toxic issue, within just four months Barker had amassed 922 marine debris balls, collected from 41 countries, on 144 separate beaches. Describing her project ‘Penalty’, she wrote: ‘Penalty is a punishment for breaking a rule in the game of football, and in relation to this project, a Penalty is the price we will all pay if we do not look after our oceans by managing the over consumption of plastic and becoming responsible for its disposal’.

In Susan Sontag’s final book ‘Regarding the pain of Others‘, published a year before she died in 2004, she reflected that sometimes ‘There’s nothing wrong with standing back and thinking’. When I consider how photographers have dealt with the enigma of visualising pollution, as well as my own small attempts, Sontag’s advice holds true; perhaps more so than Capa’s call to simply ‘get close’.

The artists and photographers featured in this volume of Toxic News have all stood back and thought about how to visualise toxicity in their work. In the first article I discuss how photographer Mathieu Asselin exposed the social and environmental damage that Monsanto is causing, in his hard-hitting project ‘Monsanto: a photographic investigation‘. In the second article I explore the use of infrared film to visualise nuclear radiation, through Edward Thompson’s innovative project ‘The Red Forest‘. Taking another perspective on Chernobyl, in the third article I showcase my own photography project ‘Disposable Citizens‘, which put disposable cameras into the hands of Ukrainians who still live around the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

Staying with the theme of radiation, nuclear geographer Becky Alexis-Martin provides the fourth article, where she looks beyond the toxic aspects of nuclear waste, and puts forward the notion of ‘para-nuclear waste‘ in her multi-sited photo-essay. As Becky explains, ‘para-nuclear waste is not radioactive itself, but is an incidental by-product of the nuclear military industrial complex‘. The fifth article continues the focus on materiality, by focusing on the innovative project ‘Rare Earthenware’ by photographer Toby Smith and the Unknown Fields collective. I explore how this project examines the toxic geographies of rare earth minerals, which involved repurposing contaminated mud from a mine in Inner Mongolia into three radioactive vases. Toby Smith retraced the toxic journey that rare earth minerals take, from a Chinese mine, to a factory, to a container ship. In sixth article, I focus on the toxic afterlives of the shipping industry, through Jan Møller Hansen’s striking photography project ‘The Graveyard of Giants‘. His images uncover the sheer scale of this perilous labour, and visualise the uneven geographies of toxic waste.

The seventh article showcases photographer Paul Shambroom’s project ‘Landscapes of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve.‘ Inspired by Dutch Landscape painting from the 17th Century, Paul pictured the secretive landscapes of the oil reserve, and contemplates his question ‘How does one photograph something that can’t be seen?’ The eighth article presents interview and photo essay with Taiwanese designer Chih Chiu, where he discusses his thought provoking project ‘A Voyage on the Planet’.

Finally, in the ninth article of this Special Issue on ‘Toxic Visions’, anthropologist Loretta Lou writes about the third annual ‘Toxic Expertise’ workshop, which this year focussed on the theme: ‘(In)visibility and Pollution: Making Sense of Toxic Hazards and Environmental Justice.’ This workshop took place at the University of Warwick, and covered many of the themes that the photographers in this volume of Toxic News explore.

The articles:

- Exposing a Chemical Company

- The Red Forest: Picturing Radiation with Infrared Film

- Disposable Citizens: viewing Chernobyl through the lens of those live there

- The derelict afterlives of para-nuclear waste

- Rare Earthenware: photography, pottery, and pollution

- Graveyard of Giants: the Toxic Afterlives of Ships

- Treasure: Landscapes of the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve

- Voyage on the planet: contemplating pollution with Chih Chiu

- Toxic Expertise Annual Workshop 2018

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Sam Kittner for letting me use his 1988 image from Cancer Alley, and to Chris Jordan for allowing me use a photograph from his series ‘Midway: Message from the Gyre’. Thanks to everyone who answered my #Hivemind question on twitter and gave me ideas for this Special Issue, including Yueming Zhang, Dan Webster, Lewis Bush, Saskia Warren, Lloyd Jenkins, Angeliki Balayannis, John Baeten, Hannah Boast and Ian Cook et al.

References:

Asselin, M., 2017. Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation, Verlag Kettler

Griffiths, P.J., 2003. Agent Orange:” collateral Damage” in Viet Nam. Trolley

Mah, A., 2014. Port cities and global legacies: urban identity, waterfront work, and radicalism. Springer.

Nixon, R., 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.

Sontag, S., 1977. On photography. Macmillan.

Susan, S., 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.