Featured Image: In front of the Taipei High Court, 27 October 2017. On the banners: “Another victory [for the plaintiffs]! Now pay compensation!” “Regrets” [for victims already deceased] Photo: Jung-lung Chang

Paul Jobin, Hsin-hsing Chen, Yi-ping Lin[1]

In her last editorial in Toxic News, Alice Mah raised the importance of translation in issues of environmental justice. We would like to follow on that intuition using our experience in the class action of the former workers of Taiwan RCA (Radio Corporation of America), a mobilization that started in 1998 and recently won a victory in court. As social scientists with a background in science and technology studies (STS), we have been involved with the plaintiffs and their lawyers for around a decade, gathering together different experts in the mobilization (epidemiologists, toxicologists, environmental engineers, etc.), collecting data from various countries, contributing to translation work (strictly speaking– from English, French and Japanese to Chinese) and helping the workers to translate their experience and medical evidence into legal causation.

A Groundbreaking Verdict for the Victims of Toxic Exposure

The authors congratulating the plaintiffs and their lawyers, at the Taipei High Court, 27 October 2017 (from left to right: Yi-ping Lin, Hsin-hsing Chen, Paul Jobin). Photo: Jung-lung Chang

On October 27, 2017, the Taiwan High Court handed down a landmark verdict on this toxic-tort class action opposing the former workers of Taiwan RCA—most of them women—against their employer and its parent companies. After nineteen years of collective struggle, the workers have obtained a solid and groundbreaking decision that could set legal precedents in similar cases of toxic-torts class actions and inspire other victims of environmental injustices around the world. Several issues that hitherto prevented such victims from getting the justice they deserve are addressed, like the complex causation of chemical exposure and the “corporate veil” draped over our age of globalized capital.

After nineteen years of collective struggle, the workers have obtained a solid and groundbreaking decision that could set legal precedents in similar cases of toxic-torts class actions and inspire other victims of environmental injustices around the world.

The Court found four defendant companies liable for workers’ impaired health and emotional distress caused by exposure to dozens of chemical toxicants while working at the factories of RCA Taiwan, which produced televisions sets for the US market from 1970 to 1992. The four companies include RCA, Taiwan and its successive parent companies, General Electric of the US and Thomson Consumer Electronics (later Technicolor SA) of France, as well as Thomson’s Bermuda subsidiary. The defendants have been ordered to pay a total sum of 718.4 million Taiwan dollars (approximately US$ 23.7 million) in compensation to 486 of the 513 plaintiffs, all former employees of RCA Taiwan.

Joseph Lin, head of the plaintiffs group of lawyers, translating into plain Mandarin the main points of the verdict, at the Taipei High Court, 27 October 2017. Photo: Jung-lung Chang

As is common in most occupational-disease and pollution controversies, the victims in the Taiwan RCA case were exposed to a mixture of a wide range of hazardous chemicals, 31 of which are covered in the Court’s decision, including substances classified by the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer as known human carcinogens, such as trichloroethylene and benzene. In countless toxic-tort cases, courts have adopted a “one-chemical-one-disease” view of causation, enabling companies that have unlawfully exposed people to a mix of hazardous chemicals to avoid any liability, as the causal links are so complex. In the U.S., the Daubert standards have made it incredibly difficult for the victims of toxic torts to prove even relatively simple causation (Jasanoff 1995, Cranor 2016). In this case, however, the Court ruled that, because RCA violated several laws and regulations at the time of its operations and failed to provide adequate protection for workers, it is responsible for the damage to their health, which has been scientifically recognized as likely caused by exposure to one or more chemicals. That damage includes cancers, miscarriages and other reproductive disorders, as well as other serious illnesses. This is a major breakthrough.

Emotion runs high when Tsu-ping Ch’in evokes her sister Tsu-hwei, who was a key member of the mobilization and who died before she could hear the verdict. Taipei High Court, 27 October 2017. Photo: Jung-lung Chang

The judges of the Taiwan High Court also awarded damages to those who have not yet been diagnosed with serious health conditions, but are emotionally distressed from witnessing numerous former co-workers fall ill and die from cancer and other illnesses. The defendants argued that “mere worries” do not warrant compensation. The judges, however, rejected that claim, since plaintiffs do also suffer from elevated health risks caused by exposure to toxic chemicals. And even when exposure has not yet yielded perceptible symptoms, carcinogens, particularly the “genotoxic,” start to alter genes in human cells at the time of contact. This approach hinges on a much more sophisticated scientific understanding of the various pathways and mechanisms through which toxic chemicals cause disease in humans.

A common feature of toxic-tort cases is for victims’ claims against the perpetrators of industrial crime to be thrown out by the court, because the statute of limitations has passed.

A common feature of toxic-tort cases is for victims’ claims against the perpetrators of industrial crime to be thrown out by the court, because the statute of limitations has passed. This happens time and again, since latency periods render the chronic diseases caused by toxic exposure hard to diagnose in a timely fashion, making it difficult for both victims and scientific researchers to discover the collective pattern of the diseases. In contrast, in the RCA Taiwan verdict, the Court found that, because the difficulty for victims to discover the truth was, in fact, caused by the company’s withholding of information, the company could not use the statute of limitations as a legitimate defense.

Another major obstacle for the victims is the well-named “corporate veil.” In 1986, GE bought RCA and its subsidiaries. Two years later, GE sold RCA to the French firm Thomson Consumer Electronics. Four years later, Thomson closed the RCA Taiwan plants, moving production to China. Thomson also sold the land and buildings of the Taiwan plants to a third party, and remitted US$ 150 million abroad. In 1998, after RCA’s persistent pollution was disclosed and the former workers realized that they were stricken with cancers, another US$ 100 million was transferred to a French bank account. The Taiwanese judges considered these actions as constituting malicious evasion of debt and obligations by RCA and its parent companies, so that the US principle of “piercing the corporate veil” would apply in this case: GE, Technicolor, and Thomson (Bermuda) thus are jointly and severally responsible for the tort liability incurred by RCA on the workers. This point will surely inspire many of those struggling against similar crimes around the world, such as those who have fallen ill from exposure to Monsanto’s pesticides.

The case is now pending in the Supreme Court for the five hundred plaintiffs, and another file has already started at the District Court for another group of one thousand plaintiffs. But this verdict has already paved the way for other cases in Taiwan, and could certainly inspire the mobilizations of other victims of toxic “slow violence” in other countries.

First court hearing for the second group of plaintiffs, at Taipei District Court, 21 December 2017. Photo: Jung-lung Chang

The Defendants Experts: Lost in Translation

In December 2016, at a crucial juncture during the appeal trial, RCA’s lawyers called a Harvard Law professor to testify in court in Taiwan for them (in English with Chinese translation). After providing the court with theories of why RCA should be allowed to walk away, the professor stated that his rate for such service is US$ 750 per hour. Before his work for RCA in Taiwan, the professor was paid US$ 250,000 by British Petroleum (BP) for a 50-page report on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, discouraging residents from suing BP for economic loss. “It is the normal rate for this kind of consultation by a law professor in the US,” he commented to the Court in Taipei. The judges and the audience were wide-eyed in amazement. This law professor is just one among many high-priced experts RCA retained from the US, China, Japan and France in their defense. Finally, on top of lawyers’ fees for the long legal battle, and translation fees for those foreign experts who could not speak Chinese, all of these high-priced experts were ultimately of no avail to the defendants.

Harvard School of Law Professor John Goldberg testifies at the Taipei High Court, 16 December 2016. Sketch: Paul Jobin

Was the translation defective? Indeed, although it was conducted by well-trained lawyers, sometimes important elements were lost in translation. The defendants could also recruit some Chinese or Chinese-American epidemiologists who could present their argument in plain Mandarin: a perfect rhetoric of negation, so as to minimize the effects of exposure to the toxic chemicals and the significant increase in risk cancer found by Taiwanese researchers.

So, what made the plaintiffs’ testimonies more convincing? As one of the plaintiffs’ lawyers summarized: “If you want to get the best translator for your case, go to the STS department!” This lawyer is not familiar with Latour, Callon and other ‘sociologists of translation,’ but his understanding of what translating implies was largely ‘contaminated’ by his regular interaction with social scientists with a STS background.

The Plaintiffs and STS’ translating skills[2]

Members of Taiwan’s STS community have played significant roles in the mobilization of the former workers both in and outside of court, and their translation skills were probably a key factor in their collaboration with workers, activists, lawyers, public-health professionals, and many volunteers students.

While the defendant lawyers’ foreign advisers and clients were accompanied by their (no doubt well-paid) professional interpreters in all the court sessions, the plaintiffs counted on student volunteers.

First of all, as suggested above, there were a lot of translations in the ordinary meaning of the word: from English—as well as from Japanese and French—into Chinese, and vice versa, from Chinese into English (or to French or Japanese), when we needed advice from our contacts abroad. The court sessions and all the documents were in Chinese, so the many documents and scientific research papers written in English had to be translated into Chinese before being presented to the judges in court. While the defendant lawyers’ foreign advisers and clients were accompanied by their (no doubt well-paid) professional interpreters in all the court sessions, the plaintiffs counted on student volunteers. There were a group of medical students and STS graduate students who actively participated in the translation efforts. Full texts of the nine RCA research papers were translated into Chinese, and sessions of English site-investigation reports, and the abstracts of many scientific reports discussed in the next two sessions were also translated before they were presented to the court by the expert witness or lawyers.

One of the numerous group meetings (of nearly one hundred) with a core group of workers, their lawyers and advisors, after the first verdict in July 2015. Photo: Jung-lung Chang

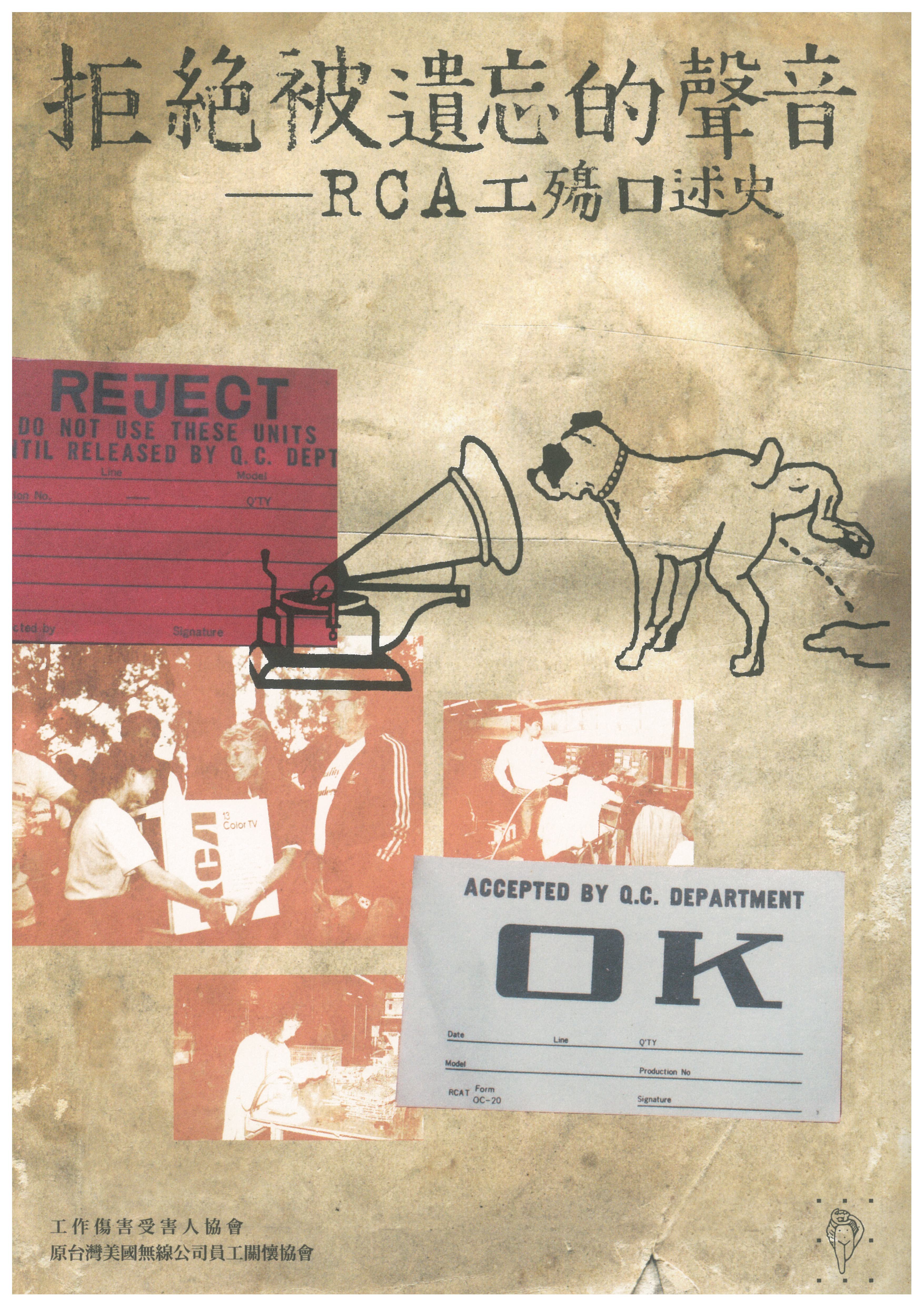

The second type of translation was to transform the RCA employees’ working and bodily experience into numbers, texts, tables and figures. Since there were more than 500 plaintiffs in the collective lawsuit, the judges ordered each plaintiff to complete a questionnaire to provide his/her working history, life styles, pregnancy, child birth, symptoms and diseases. The questionnaire was negotiated between the plaintiffs’ and the defendants’ lawyers before it was finalized. In 2011, with the help of social scientists, hundreds of lawyers, students, documentary filmmakers, and others collaborated in interviewing the plaintiffs. Information in the questionnaires was later summarized and calculated by the lawyers and volunteers in many different forms. A small group of student volunteers, under the supervision of sociologists, took further steps to collect and edit the oral history of 11 workers into an award-winning book entitled “Voices Not to Be Forgotten,” which was published in 2013 by the Taiwan Association for the Victims of Occupational Injuries (a labor NGO that has helped RCA workers since the very beginning of their mobilization in 1998).

Book cover of the award-winning Voices not to be Forgotten

Book cover of the award-winning Voices not to be Forgotten

The third kind of translation, and the most difficult one, was from science to law. Both science and law have their own cultures and languages. During the RCA trials in the district court and the appeal court, a total of eleven expert witnesses testified in court; six called by the plaintiffs and five called by the defendants. With the exception of the law professor mentioned above, virtually all of them are college professors with doctoral degrees in medicine or natural science. They were used to teaching classes of students with science backgrounds or presenting their findings to colleagues at conferences; many of them were testifying in court for the first time in their careers. There has been considerable discussion about the competence of lay juries to evaluate such scientific and technical evidence in the common-law system.

Though Taiwanese judges were not lay juries, they had very little training in science and technology. Presenting scientific findings or technical evidence to the judges, and being asked and challenged by the lawyers during cross-examination, were brand new experiences to these college professors. For instance, expert witnesses Pau-Chung Chen and Tzuu-Huei Ueng spent hours explaining to the judges how toxicological and epidemiological evidence was considered in the classification of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic chemicals by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Ueng had to describe in details how the experimental male and female mice were marked (on their tails), caged (in fives), and fed (with CA mixtures) in the laboratory. Bloody pictures of enlarged livers, ovaries, and uteri of mice exposed to organic solvents were projected in a slide presentation in the courtroom. Before the court hearings, this translation from animal to human, from toxicology to epidemiology, was discussed during brain-storming discussions with the lawyers, the workers and the STS-trained scholars. The latter worked as translators between the scientists, the workers and the lawyers.

During this nearly twenty-year-of long battle for justice, various works were therefore required to translate toxic exposure into a full recognition of the tort. Translating is often a shadow work. But through this endeavor, the victims and their supporters shared a common goal and kept faith that their efforts would not be in vain.

Hundreds of volunteer lawyers and students conduct a questionnaire survey for each plaintiff. Legislative Yuan, Taipei, 17 July 2011. Photo: Jung-lung Chang

References

Cranor, Carl. 2016 (2006). Toxic Torts. Science, Law and the Possibility of Justice. Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Hsin-hsing. 2011. “Field Report: Professionals, Students, and Activists in Taiwan Mobilize for an Unprecedented Collective-Action Lawsuit against a Former Top American Electronics Company.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, 5, 555–565.

Chen, Hsin-Hsing. 2014. “Culture of Visibility and the Shape of Social Controversies in the Global High-Tech Industry.” In Daniel Lee Kelinman and Kelly Moore (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Science, Technology and Society. London and New York: Routledge. 124-139.

Jasanoff, Sheila. 1995. Science at the Bar. Law, Science and Technology in America. Harvard University Press.

Jobin, Paul, Pascal Marichalar. 2015. “À Taiwan, une victoire pour les victimes de l’électronique globalisée” Terrains de luttes.

Jobin, Paul and Tseng, Yu-hwei. 2014. “Guinea Pigs Go to Court: Epidemiology and Class Actions in Taiwan”, editor(s): Soraya Boudia, Nathalie Jas, Powerless Science? Science and Politics in a Toxic World, pp. 170-191, Oxford, New-York: Berghahn Books.

Jobin, Paul. 2010. “Les cobayes portent plainte: usages de l’épidémiologie dans deux affaires de maladies industrielles à Taiwan”, Politix, 23, 53-75.

Lin, Yiping. Forthcoming. “Reconstructing Genba: RCA Groundwater Pollution, Research and Lawsuit in Taiwan, 1970-2014.” Positions.

[1] Paul Jobin is Associate Research Fellow at the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. <[email protected]>

Hsin-hsing Chen is Professor at the Graduate Institute for Social Transformation Studies of Shih-Hsin University, Taiwan. <[email protected]>

Yi-Ping Lin is Associate Professor and Chairperson of the Institute of Science, Technology and Society at National Yang Ming University, Taiwan. <[email protected]>

[2] This part is borrowed from Yi-ping Lin, “Reconstructing Genba: RCA Groundwater Pollution, Research and Lawsuit in Taiwan, 1970-2014.” Positions (Forthcoming).