Rowan Alcock, DPhil candidate in Politics, University of Oxford

If China truly wants to be the leader in the global effort to avoid the worst effects of climate change, it needs to once again look at the rural as the place for revolutionary answers. China’s rapid growth has, to a large extent, been sustained and powered by the rural. First by extracting surplus wealth from the rural to invest in urban industrialisation during the state socialist era (Chan, 2009, 199; Chan, 1992), and, more recently, through large scale rural-to-urban migration (Chan, 2010, 516; Pun & Chan, 2013, 180). Rural ‘hukou’[1] (household registration) holders, who would have once been expected to till the fields to supply China’s population with food, have moved to the cities to become factory workers and builders. While rural ‘hukou’ holders’ incomes increase due to this migration, significant negatives also occur. As Yan and Chen note, ‘the aging and feminization of rural producers, fragmentation of familial life[2], estrangement of social relations within villages, [and] growing rural disparity’ (Yan & Chen, 2013, 964). There is also an environmental cost due to this mass migration of the relatively young. As the rural population becomes older on average, their physical ability to labour the fields decreases. As such, they have resorted to chemical pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers as labour saving devices (Lora-Wainright, 2009, 68; Ebenstein et al., 2011). The environmental and health effects of excessive chemical inputs is well documented. Excessive chemical inputs are found to be harmful to pollinators and organisms that create healthy soils, reduce biodiversity (Carrington, 2014), and pose health risks such as acute poisoning of agricultural workers and adverse developmental abnormalities in children (UN, 2017, 5-8). In China an estimated 26 million hectares of farmland is said to be dangerously tainted by containments including pesticides (Zhang & Zhou, 2016).

The environmental and health effects of excessive chemical inputs is well documented.

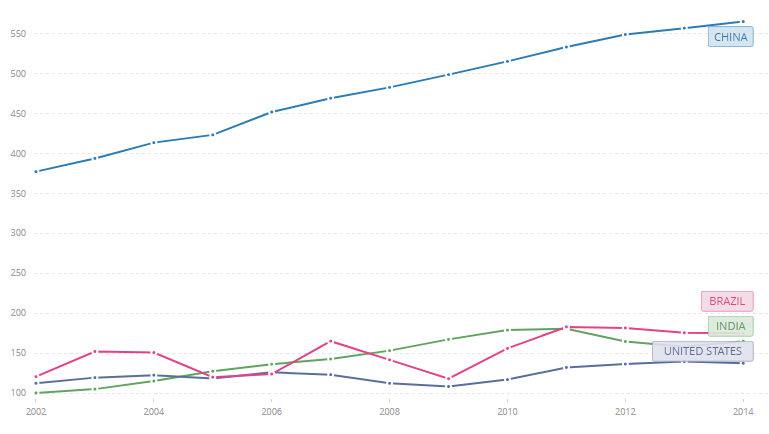

Overuse of fertiliser is another environmental issue. China’s fertilizer consumption per hectare of arable land, for example, far outstrips India, the USA and Brazil combined [Table 1/World Bank Data]

This overuse of fertilizers is responsible for a large percent of China’s C02 emissions, water pollution, and less responsive land (Ebenstein et al., 2011). The use of fertiliser in China is highly inefficient. It is estimated that ‘it would be possible to decrease the nitrogen application rate by 30-60% while maintaining the same crop yield’ (Ebenstein et al. 2011). However, Ebenstein et al. (2011) argue that fertilizer use is increasing due to labour shortages. One potential solution therefore is for migrants to return to the land.

Whilst China has only 7% of the world’s arable land to feed one fifth of the world’s population (Wu, 2011), what it has in abundance is a skilled and knowledgeable army of rural farmers armed with the knowledge of environmentally sustainable farming techniques (Schneider, 2015, 332; Cook, 2015). The frequently deployed counter-argument put forward against small scale agriculture is that it can’t feed the world, yet the evidence is that ‘There is an inverse relationship between the size of farms and the amount of crops they produce per hectare. The smaller they are, the greater the yield’ (Monbiot, 2008). A further benefit of sustainable agriculture is climate change mitigation. Abandoning intensive industrialised agricultural practices such as mono-cropping and the blanket use of pesticides and fertilizers could create an agricultural environment that has the potential to sequester up to 2.6 gigatons of carbon per year or perhaps even more (Leslie, 2017; Hickel, 2016). Biodiversity would likely improve too (Vidal, 2016; Marshall, 2016). As China searches for ‘green’ jobs for its transition to an ‘ecological civilization’, an army of ‘carbon farmers’ (Simmons, 2016) could be the next Chinese rural revolution the world desperately needs.

Abandoning intensive industrialised agricultural practices such as mono-cropping and the blanket use of pesticides and fertilizers could create an agricultural environment that has the potential to sequester up to 2.6 gigatons of carbon per year…

This is not pie in the sky thinking. The ‘return to the countryside’ movement to develop sustainable agriculture has been happening in China on a small scale in peri-urban locations (Shi et. al, 2018; Cheng, 2014). An expansion of such citizen initiatives would need large scale state support. Of course this transition is not going to be easy. Significant push and pull factors mean migrants chose urban life and urban work. Incomes from farming would likely have to rise to attract people to return to the countryside, but this could be achieved by farmers directly selling organic standard products, which demand a price premium, to consumers and/or the state paying farmers to increase biodiversity and carbon sequestration. The lack of high quality health care and education in rural areas is another important factor for China’s rural-to-urban migration. But these public institutions could be strengthened with innovative ideas such as ‘education stations’ (Yan, 2016) and government support.

It is clear that the future of agriculture needs to change. As the Report of the Special Rapporteur argued, we should ‘move away from industrial agriculture’, ‘reduce pesticide use worldwide’, ‘develop a framework for the banning and phasing-out of highly hazardous pesticides’ and ‘promote agroecology’ (UN, 2017, 22). The over-use of fossil fuel derived fertilizer is unsustainable (Horton, 2017) . Changes are needed in order to reduce the polluting of rivers and seas and to reduce GHG emissions (Wolfe et al., 2011). The development of smaller sustainable farming businesses should be a major part of this transition (Horton, 2017; UN, 2017). China has the history, the labour power, and the expertise in sustainable agriculture to create a new, science-led, rural revolution of modern small-scale agroecological farming.

References

Carrington, Damian (2014) Insecticides put world food supplies at risk, say scientists, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/24/insecticides-world-food-supplies-risk (Accessed 17/12/17)

Chan, Kam Wing (2010) A China Paradox: Migrant Labor Shortage amidst Rural Labor Supply Abundance, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 51:4, 513-530

Chan, Kam Wing (2009) The Chinese Hukou System at 50, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50:2, 197-221

Chan, Kam Wing, (1992) Economic Growth Strategy and Urbanization Policies in China, 1949–82, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 16, 2:275–305.

Cheng, Cunwang & Shi, Yan (2014) Food Safety Concerns Encourage Urban Organic Farming, Chapter 9, in; Chinese Research Perspectives on the Environment: Public Action and Government Accountability, edited by Liu Jianqiang, BRILL

Cook, Seth (2015) Sustainable agriculture in China: then and now, IIED, https://www.iied.org/sustainable-agriculture-china-then-now (Accessed 14/01/18)

Ebenstein, Avraham; Zhang, Jian, McMillan, Margaret S., Chen, Kevin (2011) Chemical Fertilizer and Migration in China, NBER Working Paper No. 17245

Yan, Hairong and Chen, Yiyuan (2013) Debating the rural cooperative movement in China, the past and the present, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 40:6, 955-981

Hickel, Jason (2016) Our best shot at cooling the planet might be right under our feet, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/sep/10/soil-our-best-shot-at-cooling-the-planet-might-be-right-under-our-feet (Accesed 16/12/17)

Horton, Peter (2017) We need a radical change in how we produce and consume food, Food Security

Leslie, Jaques (2017) Soil Power! The Dirty Way to a Green Planet, New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/02/opinion/sunday/soil-power-the-dirty-way-to-a-green-planet.html?action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=opinion-c-col-right-region®ion=opinion-c-col-right-region&WT.nav=opinion-c-col-right-region (Accessed 16/12/17)

Lora-Wainwright, Anna (2009) Of farming chemicals and cancer deaths: The politics of health in contemporary rural China, Social Anthropology

Marshall, Claire (2016) Nature loss linked to farming intensity, The BBC http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-37298485 (Accessed 16/12/17)

Monbiot, George (2008), Small Is Bountiful, http://www.monbiot.com/2008/06/10/small-is-bountiful/ (Accessed 16/12/17)

Pun, Ngai & Chan, Jenny (2013), The Spatial Politics of Labor in China: Life, Labor, and a New Generation of Migrant Workers , South Atlantic Quarterly

Schneider, Mindi (2015) What, then, is a Chinese peasant? Nongmin discourses and agroindustrialization in contemporary China, Agriculture and Human Values

Shi, Yan; Merrifield, Caroline; Alcock, Rowan; Cheng, Cunwang & Bi, Jieying, (Forthcoming), Exploring Innovative Ways for Modern Agriculture towards Rural and Urban coordinated development in China: A Participatory Study of Shared Harvest CSA and Little Donkey Farm.

Simmons, Daisy (2016) Carbon farming: What is it, and how can it help the climate?, Yale Climate Connections https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2016/10/could-carbon-farming-help-the-climate/ (Accessed 16/12/17)

UN, (2017), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, United Nations General Assembly. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G17/017/85/pdf/G1701785.pdf?OpenElement (Accessed 16/12/17)

Vidal, John, (2016) A switch to ecological farming will benefit health and environment – report, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jun/02/a-switch-to-ecological-farming-will-benefit-health-and-environment-report (Accessed 16/12/17)

Wolfe, David; Beem-Miller, Jeff; Chatrchyan, Allison; & Chambliss, Lauren, (2011), Farm, Energy, Carbon and Greenhouse Gasses, Cornell University http://climatechange.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/farm_energy.pdf (Accessed 14/01/18)

Wu, Yanrui, (2011) Chemical fertilizer use efficiency and its determinants in China’s farming sector. China Agricultural Economic Review.

Yan, Haijun (2016) Sparrow Schools: The Empty Shells of China’s Countryside, Sixth Tone http://www.sixthtone.com/news/626/sparrow-schools-the-%3Cspan-class%3D%22highlight%22%3Eempty%3C%2Fspan%3E-shells-of-chinas-countryside (Accessed 16/12/17)

Zhang, Yan & Zhou, Chen (2016) China’s tainted soil initiative lacks pay plan, China Dialogue, https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9028-China-s-tainted-soil-initiative-lacks-pay-plan (Accessed, 14/01/18)

Zhou, Minhui; Murphy, Rachel; Tao, Ran (2014) Effects of Parents’ Migration on the Education of Children Left Behind in Rural China, Population and Development Review, Vol.40(2), pp.273-292

[1] The ‘hukou’ system is an internal resident permit which allocates state services at place of residence. It is difficult – although not impossible – to change ‘hukou’ residency. For more information on the ‘hukou’ system see Chan (2009).

[2] For information on ‘left behind’ children see Zhou et al. (2014)