David McRobert[1], Jordan Shay[2] and Julian Tennent-Riddell [3]

The Chevron case, which has been called the world’s largest environmental justice case, involves a decades-long dispute between members of Ecuadorian communities and the Chevron Corporation. In 2011 the Supreme Court in Ecuador confirmed the following wastes, all attributed to the United States-based company Chevron-Texaco, had been deposited in jungles, waterways, roads and farmlands adjacent to the communities: approximately 880 Olympic pool-sized pits filled with petroleum waste; 650 thousand barrels of crude oil spilled in the jungle and on farmland; and an estimated 60 billion gallons of toxic waste dumped into waterways. In addition, the court determined that more than 1,500 kilometers of Amazonian roads have been covered in crude oil in recent decades.

The plaintiffs also filed considerable evidence of elevated cancer, other health problems and contamination of traditional food supplies related, which provided the basis for an initial judgment of more than $17 billion. This lower court decision then was upheld by an Ecuadorian appeals court, and reduced to $9.5 billion US by the National Court of Justice of Ecuador. However, the Ecuadorian subsidiary of Texaco-Chevron was bankrupt and this required the plaintiffs to seek compensation from the company’s US-based operation.

The plaintiffs, including members of the Secoya tribe and representatives of the Union of People Affected by Texaco’s operations (UDAPT, by its Spanish initials) have traveled to the United States, Argentina, Brazil and now Canada to litigate the case and have appealed to the International Criminal Court. Since 2012 the plaintiffs have been seeking to enforce in Canadian courts a US$9.5 billion Ecuadorian judgment against Chevron for environmental damage. The plaintiffs argue that the judgment can be enforced in Canada because Chevron has a Canadian subsidiary, Chevron Canada.

In August 2016 the Ecuadorians suffered a serious setback when Judge Lewis Kaplan of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York issued a unanimous, 127-page affirmation of an earlier ruling that the $9.5 billion judgment had been tainted by evidence of fraud, bribery, evidence tampering, and other alleged “shenanigans”. This civil racketeering (RICO) suit was brought by Chevron and has blocked the plaintiffs from trying to collect on the judgment in the U.S., and barred their chief U.S. lawyer and strategist, Steven Donziger, from collecting any fees from the judgment.

Thus far, the US courts have determined, and the US business press claims, that Donziger, a “self-styled social activist and Harvard educated lawyer”, has engaged in conduct unbecoming.[4] While the US Federal courts in New York have ruled that Donziger’s campaign has devolved into a racketeering conspiracy involving bribery and fabricated evidence, many supporters of the Ecuadorians disagree. In response, in 2014, 17 non-government organizations began to file amicus briefs (Friend of the Court) seeking to overturn the controversial rulings by Judge Lewis Kaplan in Chevron’s retaliatory RICO action against the affected communities.[5]

There is no doubt that Donziger has waged his campaign in an aggressive manner strongly reminiscent of the tactics used by tort lawyer Jan Schlichtmann in the Woburn, Massachusetts TCE contamination case.[6] That landmark and controversial case was brilliantly described and detailed by Jonathan Harr in his 1995 book, A Civil Action (1995), which later was made into a major motion picture starring John Travolta as Schlichtmann. However, leaving legal tactics aside, it has been documented for decades that corporations have undertaken similar activities such as bribery of public officials and coercion in an effort to promote development activities with negative social and environmental consequences. Some would be tempted to argue there is an apparent double standard with respect to governance: international and multinational corporations are well insulated from complex environmental justice legal actions undertaken in developing nations whereas plaintiffs and their counsel have few remedies to pursue justice. No doubt this is one reason why federal, national, and state governments in many developed nations have begun to address this situation by enacting anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws that apply to corporations based in within their territories and operating overseas in developed nations.

Due to the findings against Steven Donziger, several of the firms supporting and funding the litigation efforts, withdrew entirely from the case. Burdford Capital had initially pledged to invest $4 million to assist the plaintiffs with the Chevron case but withdrew their support in April 2013 after it was announced that it had concluded the plaintiffs’ lawyers had misled Burford. In May of 2014, Washington law firm Patton Boggs, who had signed on as co-counsel with Donziger agreed to pay $15 million to Chevron and withdrew from the law suit. They however did not publicly admit to any wrongdoing in connection with the settlement. After Chevron brought conspiracy claims against Woodsford Litigation Funding Limited for the company’s role in funding and advancing Dozinger’s lawsuit, the two companies reached a settlement to avoid further litigation. The UK based litigation funding firm had previously provided $2.5 million to fund the law suit.

To date, developments in Canada have been mixed. A separate paper by one of the authors presented in Ontario Bar Association’s Environews in March 2016 traced some of the controversies related to the Canadian case and explored the developments in Canada prior to February 2016.[7] Chevron has consistently sought to argue that it is inappropriate for the Canadian courts to “pierce the corporate veil” even though the veil has been pierced by the courts, Legislatures and the federal Parliament for decades in relation to social welfare issues such as food and product safety, environmental contamination and occupational health and safety. The plaintiffs successfully appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2015 and the court allowed the case to go a full trial.[8] The authors have been following the case closely for a number of years and the principal author was involved in a controversy related to a proposed intervention by the Canadian Bar Association which would have sided with Chevron.

In early 2017, an Ontario lower court ruled against the plaintiffs, holding that the shares and assets of Chevron Canada could not be seized to satisfy the Ecuadorian judgment against Chevron.[9] The court held that Chevron Canada is not an asset of Chevron, but rather a separate legal person, despite the plaintiffs’ arguments that Chevron Canada is “wholly-owned and controlled by Chevron Corp. for the sole benefit of Chevron Corp.’s shareholders”.[10] Further, the court ruled that the “corporate veil” should not be pierced in this case, upholding the principle of corporate separateness and using a narrow reading of the test for piercing the corporate veil. The decision, while applauded by corporate lawyers, is viewed by lawyers for the plaintiffs as incorrect in law.[11] The plaintiffs have indicated they are seeking leave to appeal the decision.[12] This was a disappointing setback after a successful appeal to the SCC (decided in 2015) allowing the case to go a full trial.[13]

In May of 2017, Amazon Watch, the Rainforest Action Network and 15 other groups filed another amicus brief with the U.S. Supreme Court on petition for a “Writ of Certiorari” (judicial review).[14] The brief outlines the illegal and unethical tactics Chevron and its lawyers used to obstruct the lawsuit in Ecuador. The brief alleges that Chevron paid off its star witness, a corrupt former judge who ultimately admitted after trial that he lied in his testimony in the case. The judge’s evidence, the brief argues, formed the bedrock of many of the District Court’s key conclusions. Additionally, the brief urges courts to refrain from investigations into foreign trials as they can often be liable to get them wrong and result in lawsuits bouncing between different countries. Ultimately, the brief is seeking certiorari on the question of whether “federal courts have jurisdiction to entertain preemptive collateral attacks on money judgements issued by foreign courts”.

This case provides another example of lengths multinational corporations will go to avoid liability in the developing world for environmental disasters they have caused.

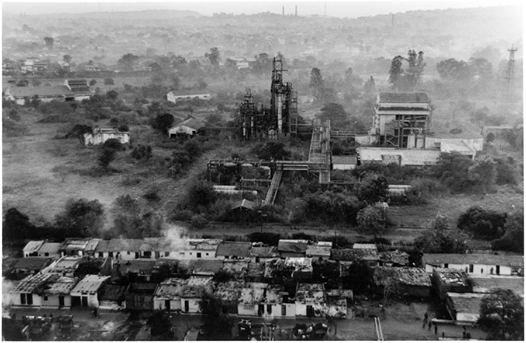

For centuries, companies and corporate charters based in Europe, North America and other developed nations have wreaked ecological, political and social havoc by exporting dangerous substances, techniques, resource management ideas (such as sustained yield) and socio-technical systems. Some of the disruptions these dangerous chemicals, systems and technologies have caused are shocking in their scope, such as the infamous industrial disaster in Bhopal, India in 1984.[15]

On the night of December 2, 1984 the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh leaked methyl isocyanate gas and other chemicals. The toxic substance made its way in and around the shantytowns located near the plant, resulting in the exposure of hundreds of thousands of people. Estimates vary on the death toll. The official immediate death toll was 2,259 and the government of Madhya Pradesh confirmed a total of 3,787 deaths related to the gas release.[16] An Indian government affidavit filed in 2006 stated the leak caused 558,125 injuries including 38,478 temporary partial and approximately 3,900 severely and permanently disabling injuries. If this accident had happened in Canada, billions would have been paid in compensation and Union Carbide would have had to declare bankruptcy. Instead, a U.S. court ruled that damages would be based on Indian law and mere millions were paid out, protecting thousands of Union Carbide shareholders and their employees mostly based in developed nations.

The Bhopal disaster graphically showed how we export environmental and social risks to developing nations when we transfer our dangerous technologies and place them in the hands of companies, subsidiaries, technologists and engineers in developing nations who may not understand the risks associated with their use. There are dozens of other examples. A more recent example is provided by the handling of two massive oil spills by Shell operations in the Niger Delta in 2008 and 2009. Although the evidence of environmental damage and social impacts was compelling, Shell evaded responsibility for years through its influence in the government and claims of sabotage. In 2015 Shell was ordered to pay £55 million to 15,600 farmers and fishermen after British law firm Leigh Day and Amnesty International helped represent them in an action against the oil conglomerate.

If Chevron is successful in its argument that it is inappropriate for the Canadian courts to “pierce the corporate veil” this could prove to be a significant setback in relation to regulation of corporations with respect to social welfare issues such as food and product safety, environmental contamination and occupational health and safety.

Indeed, those non-government organizations and government officials advocating for greater accountability, transparency and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the oil and gas, mining, forestry and manufacturing sectors in Canada and in those developing nations where Canadian-based companies undertake developments may find their legs cut at the hips rather than their knees.

Keywords: Chevron; environmental justice; ecological history; indigenous rights; oil and gas

Featured photo credit: Getty Image/AFP/ R. Bruendia

Endnotes

[1] David McRobert is an environmental, aboriginal rights and energy lawyer based in Peterborough, Ontario. email: [email protected]

[2] Jordan Shay received a B.A. from Queen‘s University in Global Development Studies and an LL.B. from the University of London with a specialization in International Law. He worked under the environmental law portfolio at Thomson Reuters and is currently a Student-at-Law articling for David McRobert. Email: [email protected]

[3] Julian Tennent-Riddell has a B.A. Honours degree in Indigenous Environmental Studies from Trent University (2014) and recently graduated with a J.D. from the University of British Columbia Faculty of Law (2017). He has been actively involved in various advocacy efforts for environmental justice. Julian is hoping to practice law in the fields of human rights and environmental law. Email: [email protected]

[4] Paul M. Barrett, Law of the Jungle: The $19 Billion Legal Battle Over Oil in the Rain Forest and the Lawyer Who’d Stop at Nothing to Win. New York: Crown, Sept. 2014.

[5] Amazon Watch, Human Rights Organizations File Amicus Brief Opposing Chevron RICO Decision Ruling Poses Serious Threat to Free Speech and Democracy, July 15, 2014.

[6] Anne Anderson et al. v. W.R. Grace & Co. et al. (1982-1987). For a summary, see http://serc.carleton.edu/woburn/Case_summary.html As described on the website, “This landmark case centered on the alleged contamination of two municipal supply wells (G and H) in Woburn, Massachusetts, by three local industries. The plaintiffs were a group of eight families that lived in a part of town served by the two municipal wells. The defendants were W.R. Grace & Co., owner of the Cryovac Plant, UniFirst Corporation, owner of Interstate Uniform Services, and Beatrice Foods, Inc., owner of the John Riley Tannery. The plaintiffs alleged that ingestion of toxic chemicals used at these industries, which were measured in water samples from the municipal wells, were responsible for severe health effects. Children of seven of the plaintiffs contracted leukemia. Five of the children died from leukemia or complications of having leukemia. The spouse of one plaintiff contracted acute myelocytic leukemia and died. The suit was filed in May 1982 in Middlesex County Municipal Court. A motion was filed by one of the attorneys hired by W.R. Grace to remove the case to federal court. The case was assigned to Judge Walter J. Skinner. Discovery began in September 1984. Because of the scientific complexity of the epidemiological, geological, and hydrological evidence, Judge Skinner divided the trial into four parts. The first part dealt with the subsurface movement of the contaminants to the wells. If any contaminant used at the defendants’ properties was found to reach the wells within the period when wells G and H were in use (1964 to 1979), the trial would proceed to the next two phases dealing with the health effects. The fourth phase would address damages. The period between submission of the plaintiffs’ claim and the beginning of trial discovery was marked by the filing of numerous contentious motions and controversial rulings by Judge Skinner as well as by the death of another of the plaintiffs’ children. Prior to the trial, UniFirst settled out of court for $1.05 million. The lawsuit originally was handled by the firm of Reed & Mulligan after Donna Robbins inquired about filing a personal injury claim on behalf of her son Robbie. In 1982, Jan Schlichtmann, who had worked at Reed & Mulligan, visited the plaintiff families in Woburn and eventually took on the case with his firm, Schlichtmann, Conway & Crowley. The final complaint filed in federal court was listed as Anne Anderson et al.”

[7] D. McRobert, Chevron Case Heads back to Ontario Trial Courts: Supreme Court of Canada rules Ecuadorian villagers can go ahead with Enforcement case against Chevron, Aboriginal Law Section Newsletter, Ontario Bar Association, March 2016.

[8] Chevron Corp. v. Yaiguaje, [2015] 3 SCR 69, 2015 SCC 42.

[9] Yaiguaje v Chevron Corporation, 2017 ONSC 135.

[10] Ibid at para 33.

[11] Alex Robinson, Plaintiffs to Appeal Chevron Decision, Law Times (13 February 2017).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Chevron Corp. v. Yaiguaje, [2015] 3 SCR 69, 2015 SCC 42.

[14] Amazon Watch, Civil Society Groups Ask U.S. Supreme Court To Reject Chevron’s Attempts to Suppress Free Speech and Undermine Historic Amazon Pollution Case Supreme Court Presented With Evidence of Chevron’s Bribery, Intimidation and Retaliation Against Civil Society Groups and Indigenous Communities, May 1, 2017. To read the Amazon Watch brief, see here.

[15] The information in this article on Bhopal is based on analysis which appears in D. McRobert, Asbestos in Quebec, Part 2: Why We Export Death – Perhaps we feel “Lucky”?, Hazardous Materials Management Magazine, August 11, 2012.

[16] Others estimated 8,000 died within two weeks and another 8,000 or more died within 10 years of the spill from gas-related diseases.