Dr Thom Davies, Research Fellow, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick: @ThomDavies

This month Toxic Expertise held our second annual workshop at the University of Warwick. The two-day event involved over thirty scholars and members of the public who shared their experiences of environmental justice, pollution and citizen science from a variety of perspectives. Environmental justice experts Phil Brown (Northeastern University) and Gwen Ottinger (Drexel University) gave keynote addresses, and fourteen other academics from a range of disciplines presented fascinating research papers that highlighted cutting edge scholarship at the nexus of citizen science and environmental justice.

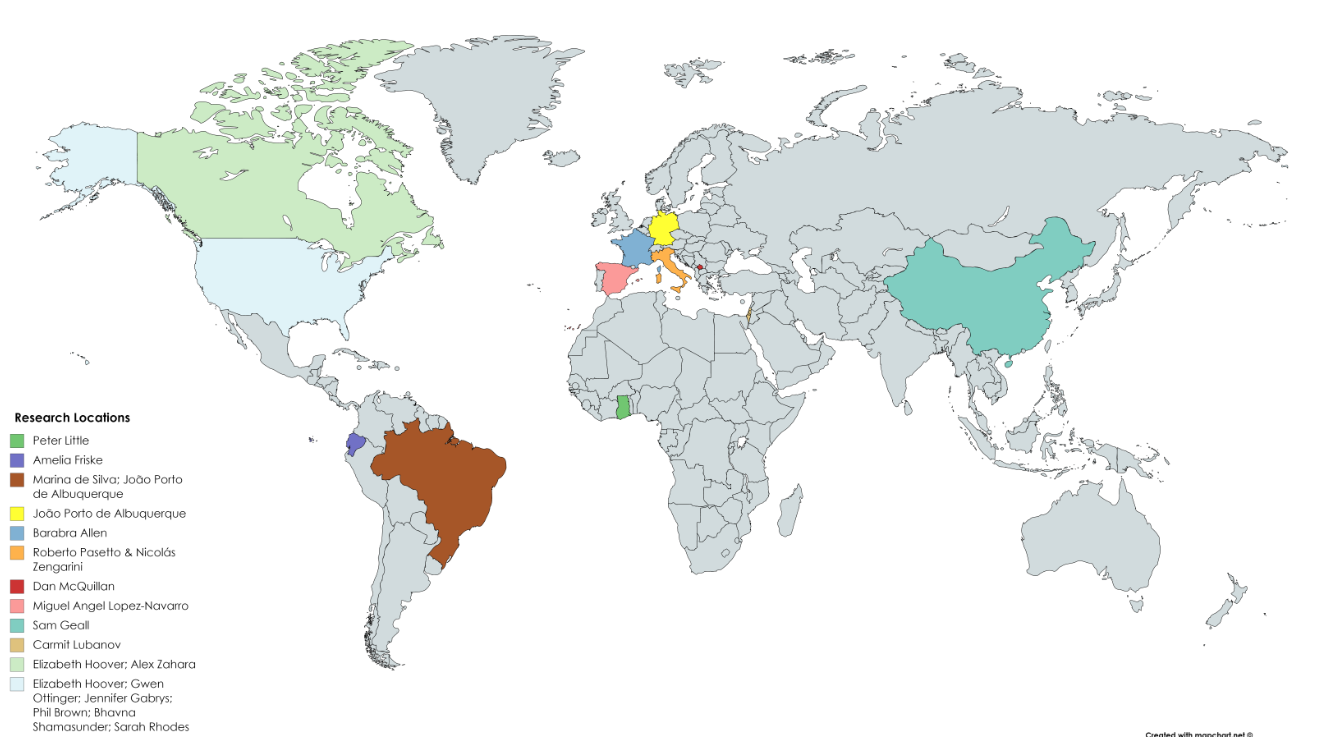

Participants showcased recent research from twelve different countries in the Global North and South.

One of the things I found most exciting about the workshop was the breadth of geographic case studies brought into the conversation. As shown in the map below, participants showcased recent research from twelve different countries in the Global North and South, including Kosovo, China, Spain, Ghana, France, Ecuador and Brazil. A key point of reflection was the transferability of environmental justice across different scales and geographies. Throughout the case studies, environmental injustice appeared as a seemingly universal consequence of uneven power relations impacting the lives of diverse groups across the world. More optimistically however, several of the papers also highlighted citizen science projects that are utilising alternative perspectives about pollution, and politicising environmental concerns.

The kite physically connects itself to the communities using it, making it a much more effective and compelling tool for citizen science.

We were lucky with the weather during the workshop, and fortunate to be joined by Cindy Regalado from Public Lab and UCL, who gave a fantastic ‘Kite Mapping’ demonstration. She showed us how to set up a kite photography kit, and how kite flying can be used to monitor environmental injustice from a ‘bird’s eye’ perspective. With increasing restrictions on the use of drone technology, this simple yet effective technology for witnessing changes to the landscape seemed particularly apt. As she explained, the way the kite physically connects itself to the communities using it, makes it a much more effective and compelling tool for citizen science monitoring:

After a brief introduction from Alice Mah (University of Warwick) who runs the Toxic Expertise project, Phil Brown opened the two-day event with a keynote address that introduced the history of environmental justice and popular epidemiology, linking contemporary work with pioneering justice campaigns such as Love Canal (1978). He discussed the notion of ‘toxic trespass’, before asking us to consider the role of ‘worry’ within research; how environmental justice campaigns often involve worrying local communities about a toxic threat, which is sometimes necessary to galvanize political action. He also discussed the importance of sharing research with local communities, and their right to know. For example, he explained that if ‘you take that data from there, you give it back’. This echoed the approach of many of the participants’ papers throughout the workshop. He also stressed the importance of communicating research findings in an understandable way, such as using terms like ‘weed killer’ instead of ‘pesticide’ when communicating with local communities.

…if ‘you take that data from there, you give it back’. This echoed the approach of many of the participants.

Jennifer Gabrys’ (Goldsmiths University) and Joao Porto de Alburquerque (University of Warwick) gave talks themed around the theme of ‘Citizen Sensing’. Jennifer, who leads an ERC project ‘Citizen Sense’, drew upon her recent research with communities living near fracking sites in rural Pennsylvania. She discussed the installation and use of air quality monitoring kits, describing how citizen sensing practices have given rise to new forms of evidence, and how using data that is ‘just good enough’ has the potential to significantly impact environmental politics. Joao Porto de Alburquerque then discussed how citizens are engaged in sensing, curating and making sense of geographic data in the context of disaster and urban resilience. He questioned the “citizen as sensor” metaphor, giving examples from his research of how citizen science has been contrastingly used in urban settings of both Germany and Brazil. Joao also questioned the implicit idea that citizen science leads to empowerment, emphasising how ‘sensing can be detached from sense making’.

The next talk by Barbara Allen (Virginia Tech University) introduced her in-depth research with communities in southern France who live near petrochemical facilities. She continued the theme set by Joao on the importance of ‘sense making’, emphasising how researchers must ensure they focus on ‘sensing the things people want to know’. Through her extremely comprehensive and inclusive participatory research design, Barbara has not only been producing detailed citizen science data with communities, but has striven to fully include local communities in the analysis and use of the data. She described the intensive community workshops that have helped to collaboratively analyse the research findings, in an area of France so polluted that ‘if you’re there for a day your eyes burn’. It was fascinating to hear about her environmental justice project, which takes the notion of ‘participation’ extremely seriously.

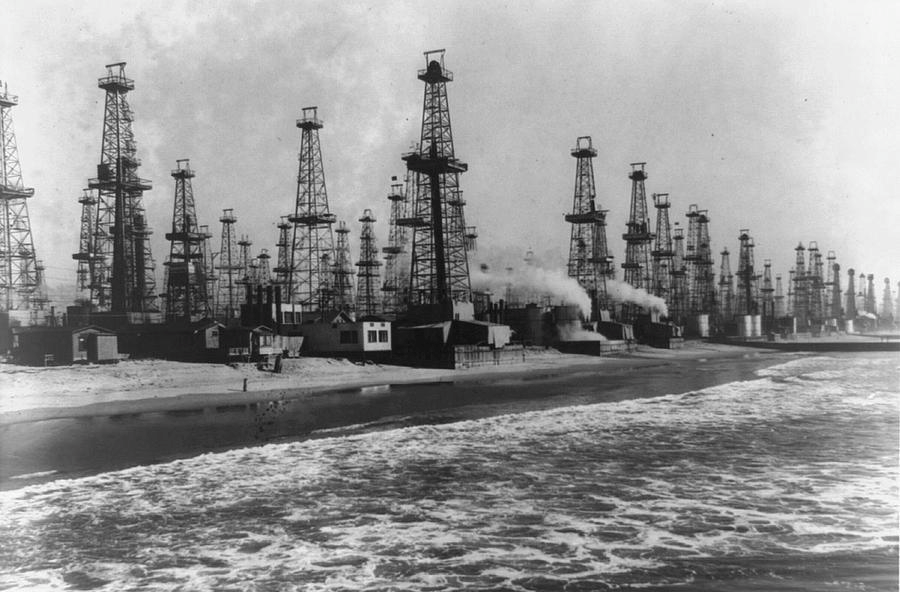

Continuing the petrochemical theme, Bhavna Shamasunder (Occidental Collage) gave a paper on neighbourhood oil drilling in California. She showed striking photographs of ‘nodding donkey’ oil pumps abutting suburban housing in the ‘urban oil fields’ of LA, as well as interesting historical images of the intensive petroleum landscape of California in the early 20th century. Incredibly, there is currently no law in California to ensure there is a buffer between oil sites and where people live, which exposes local residents to increased health risks. Like with countless other cases of environmental injustice in the USA, Bhavna explained how there was a clear racial dimension to the distribution of environmental disadvantage in LA: she showed how oil rigs are better enclosed and hidden in white neighbourhoods than in places of colour. Also focusing on the USA, Sarah Rhodes (University of North Carolina) gave a paper on antibiotic-resistant bacteria in North Carolina’s intensive hog production regions. Sarah’s PhD is utilising community-based participatory research to examine potential environmental issues caused by the density of industrial agriculture, in a place synonymous with pig farming.

“We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe”- Frantz Fanon

During a panel themed around ‘Citizens and Air Pollution around the World’, Miguel Ángel López-Navarro (Universitat Jaume I, Castelló) presented his research based in two petrochemical sites in Spain. He discussed how petrochemical companies, as well as civil society organizations and public authorities in Tarragona, are all faced with the challenge of legitimating discourses about how to manage environmental risks. Connecting to Phil Brown’s discussion of the political use of ‘worry’ within environmental justice campaigns, Miguel also discussed the role that confrontation plays within environmental controversies. Taking us from Spain to Kosovo, Dan McQuillan (Goldsmiths) then discussed his participatory research with young people in Pristina who are monitoring air pollution as a means of political activism. He discussed the notion of ‘bio-solidarity’, which I thought was an interesting counterpoint to the idea of ‘citizen science’, and detailed his Making Sense Kosovo ‘mannequin’ campaign which campaigns against urban smog. He ended his talk with a very apt Frantz Fanon quote that summed up the politicisation of polluted air: ‘We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe”. It was very interesting finding out about the role of environmental monitoring and political activism in Kosovo, which Dan described as a place that has already experienced the ‘post truth politics’ that we are now witnessing in the USA and UK.

Carmit Lubanov (Association of Environmental Justice in Israel) discussed her detailed research into environmental injustice in Israel, where she has focussed on inequality in sewage, water, public transportation, air pollution and open spaces. As with countless other examples of environmental injustice, economically vulnerable communities in Isreal – predominantly Arab towns and villages – are most subject to environmental risks. Roberto Pasetto (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) followed Carmit with a paper about heath profiles of communities living near contaminated sites in Italy. As with Carmit’s paper, Roberto’s epidemiological research found evidence of an uneven distribution of hazards and risks due to the combined impact of contamination and socioeconomic disadvantage. For example, health impacts near National Priority Contaminated Sites in southern Italy, which is predominantly more economically marginalised, were much worse than those in the north. Moving the discussion to China, Sam Geall (University of Sussex) gave a presentation about Chinese climate-change journalism. He detailed how the environment has been officially framed by the Chinese government throughout its modern history, and pointed to how today, climate change represents a destabilizing phenomenon with non-linear and uncertain dynamics.

Gwen Ottinger (Drexel University) kick-started the second day of the workshop, giving a key note address that focussed on her real-time ambient air monitoring research in California. She described her participatory design project ‘Meaning from Monitoring’ which works with residents of ‘frontline’ refinery communities in the San Francisco Bay area who live in places where toxic gasses are a potential health threat. Despite the existence of vast quantities of real time data, Gwen described how air quality data alone does not necessarily advance the cause of environmental justice. She questioned the usefulness of accurate data on environmental issues, if it was not being used by the communities involved. She also talked about the tension between advocacy and academic rigour, and whether there was anything inherently ‘special’ about citizen science. You can read more about her ongoing research and the four lessons she learnt from this project in this Toxic News article.

Following Gwen, Alex Zahara (Memorial University) gave a talk about communities’ right not to know about environmental controversies, and the role of ‘refusal’ within citizen science. This was an interesting counterpoint to Phil Brown’s invocation of ‘worry’ the day before, and Alex drew upon feminist geography scholarship, talking reflexively about ethnical concerns and challenges he has faced in his own research. He described his ultimate decision not to focus on indigenous communities, but instead turn the lens on his own community. Elizabeth Hoover’s (Brown University) presentation about environmental injustice within an indigenous Mohawk community of Akwesane problematized the normalised sovereign category of ‘citizenship’ implicit in ‘citizen science’ through her focus on the experience. The word “Citizen”, for example, may have different meanings in tribal communities. She described how the Akwesane territory transects Canadian and US sovereign space, and how the binaries between citizen and scientist, between subject and researcher were blurred through a participatory health research process. She detailed how scientific health advice was amended to meet the needs of Mohawk community, such as the need to fish, but only after community consultation.

The word “Citizen” may have different meanings in tribal communities.

Starting the last session of the day which was themed around ‘Witnessing and Visualising’, Peter C. Little (Rhode Island College) discussed his on-going research with toxic E-waste sites in Ghana. He explored the use of participatory photography as a tool to reflexively challenge insider/outsider perspectives on environmental injustice. He detailed the physical and highly visual health impacts of living amongst the remnants of discarded technology and his talk questioned the use of visual methods to capture the structural violence that the E-waste workers are subjected to. With photography often being blinkered to anything but the most dramatic symptoms of wider structural forces, participatory photography can often conceal as much as it illuminates. He discussed how his participants have stayed in contact with him by sending photographs of their everyday lives in the E-waste site, which reminded me of work by Katz (1994) and Koyabashi (1994) on extending ‘the field’ beyond the traditional field research setting. Marina Da Silva (Goldsmiths) carried on the visual theme to talk about visual pollution in São Paulo. As an academic and artist, Marina is exploring how the city’s ‘Cidade Limpa’ (Clean City) law is attempting to fight ‘visual pollution’ without actually defining what counts as ‘visual pollution’. With reference to a video of the research installation, she discussed how the malleable definition of visual pollution relates to the ownership of public space and the urban environment in Brazil. You can read more about Marina’s visual sociology research in this recent Toxic News article.

Participatory photography can often conceal as much as it illuminates.

Amelia Fiske (Christian-Albrechts- Universität zu Kiel) concluded the presentations at the workshop, with a discussion of her research on ‘Toxic Tours’ and bearing witness to petrochemical pollution in the Oriente region of Ecuador. She described how rapid environmental and social change resulting from colonization, palm tree cultivation and oil production, has created a number of environmental issues that are not experienced equally. Amelia described how the juxtaposition of toxic tours with the hidden reality of this environmental injustice reveals the profoundly unequal toxic burdens suffered by some bodies and not others. She also argued for greater emphasis on bodily knowledge and bodily experience in constructing alternative expertise about environmental issues.

Over the two-day Toxic Expertise annual workshop it was fascinating to hear about such a broad range of approaches and engagements with citizen science, pollution and environmental justice. During the question and answer sessions we grappled and discussed complex themes: from problematizing the categories of ‘citizen’ in ‘citizen science’, to pondering what counts as ‘justice’ in ‘environmental justice’, to what we mean by ‘success’ during citizen science campaigns. As Jennifer Gabrys remarked, how do we know when we have enough data? Gwen Ottinger raised the question of what – if anything – makes citizen science ‘better’ than other forms of knowledge production, and asked us to consider what is gained and lost by framing this form of data gathering in this way. Another reoccurring question was how well environmental injustice themes could travel across different spaces and scales, given that each case study is inherently imbued with local perspectives, place-based specificities, and details that would be harder to universalise. The geographies of environmental injustice are undoubtedly uneven, yet the breadth of case studies discussed at this workshop, as well as the multiple ways the environment is being explored and politicised in participatory ways, gives me confidence that researchers and communities alike are taking environmental justice seriously.