Dr Deana Jovanović, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Center for Advanced Studies of Southeastern Europe, University of Rijeka

The smoke had its own character, and evoked a particular sentiment.

Featured image: Bor, July 2015. Photo credit: Dragan Stojmenović

The town of Bor is a copper-processing town in East Serbia that developed right “under the chimney”. The rundown smelting plant and the worn out sulphuric acid plant (that was supposed to absorb the toxic gases from the smelting plant) are both located close to the old town centre. When I was living in Bor between 2012 and 2013, the by-product of the smelting plant or so-called “smoke” – how people from Bor referred to air pollution – frequently “fell down” onto the streets of Bor. It contained a great amount of sulphur dioxide, but also arsenic, lead, zinc, cadmium, and soot, among other particulate matter.

Bor 2012, Photo credit: author

Bor 2012, Photo credit: author

While doing my anthropological fieldwork, I spent some time in the streets affected by this smoke. I could sense a shadowy, squeaking feeling in my lungs and felt short of breath for the next half an hour. This repulsive smoke gave me strong nausea and a cough. Despite the fact that many Bor residents (Borani) disliked living in the most polluted town in Serbia, there was something peculiar about this smoke. There was something powerful about it, especially people’s endurance under the smoke.

The smoke had its own character, and evoked a particular sentiment. For instance, a friend of mine commented once while we were observing the smoke coming out of the smokestacks:

“It’s somehow šmekerski”.[1]

“What do you mean?” I asked him.

“It’s like when you smoke a cigarette [he imitated smoking with enjoyment] and you look into the smoke and you say ‘To!’ [‘Yeah!’]”.

The ambivalent dispositions of Bor people towards the smoke reflected perceptions of both hope and risk at the same time (see Jovanović 2016 ). Very often, residents expressed semi-ironic celebrations of the smoke. By adopting this stance, they portrayed themselves as strong, resilient people who had the capacity to endure hazards. The people of Bor positioned themselves as individuals who adapted and heroically endured the smoke. They represented themselves as intoxicated subjects who were almost resistant to toxicity. The following glimpse from Borani’s everyday relationship with the smoke can give you a sense of their heroic endurance.

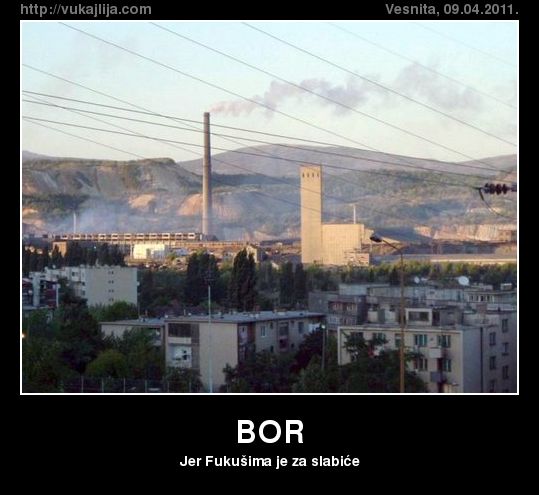

For instance, one of my interlocutors from Bor shared on his Facebook wall a poster from a website, a popular Serbian user-generated urban dictionary and humorous encyclopaedia (vukajlija.com). The poster represented Bor’s landscape of buildings and the smoke descending on the town from the smelting factory chimney. Under the image there was a caption: “BOR. Because Fukushima is for sissies”.

“BOR. Because Fukushima is for sissies”. Source : www.vukajlija.com

Comparing intoxication with the recent nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant, endurance under pollution in Bor was represented as much more severe and more heroic. People who commented on this picture made jokes about how people from Bor had a particular stamina that stemmed from their intoxication.

Another poster shared on Facebook by a Bor resident is also illustrative:

A comic taken from the author’s friend’s Facebook page in January 2014.

Superman was being defeated in an arm-wrestling duel with a skinny young boy from Bor. Superman, getting his hand pinned down on the table, asks the boy in wonder: “Where are you from, which planet are you from?!!” The boy answers “From Bor, you pussy!!”

I could also hear the stories about an image of the “rough” Boranin. While I was strolling down the main street with one of my interlocutors from the local commune, her daughter, who also joined us that evening, told me that she saw a TV report from a resort at a lake somewhere in Serbia. According to her, in this TV report people were making a barbeque and burning leaves that created an enormous amount of smoke around them. One man on TV was asked whether he was bothered by the smoke. According to her, the man replied: “I’m from Bor, man, how can it bother me?!!” she recounted proudly, while smiling. She explained that people in Bor were tougher since they knew how to bear such intoxication.

What I encountered in Bor and what these and similar humorous representations encapsulated was a particular sense of endurance under pollution and a perverse feeling of stamina that people claimed they obtained just from enduring pollution. This was accompanied by a feeling of pride and a sense of belonging to such a polluted, toxic environment, sometimes even mixed with a particular ironic enjoyment of such endurance and impudence.

But, how can we fully understand Borani’s endurance under the smoke and anthropologically make sense of it?

“Stuckedness” – or ‘Sve se ne zna’ (“It’s absolutely known that nothing is known”)

Heroic endurance under the smoke was a strategy that Borani used to negotiate the stigma of the toxic exposure of their town. People used this strategy to deal with their feelings of powerlessness to do anything to change the situation.

First, let me note that endurance under the smoke has had a long history in Bor. Even an anecdote from the Yugoslav times brings it to mind: when the Yugoslav president Tito visited the smelting factory in Bor in 1948, many members of Tito’s escort started to cough from the smoke while entering and exiting the smelting plant. Tito turned to his escort and said: “Oh, you are all so feeble [ … ] You see how we workers endure it very well” (Radulović 1987: 66). Tito was here clearly making a reference to his apprenticeship to a locksmith and work as an itinerant metalworker before the World War II. The leitmotif of endurance is here present, only in the context of industrial socialist working endeavours.

Whilst Bor was once a symbol of socialist industrial prosperity and modernism (always polluted), after the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the 1990s (and especially after 2000) it became emblematic of post-socialist crisis, pollution, precarious lives, and a devastated economy. Today the whole town is still characterised by its mono-structural economy, where the copper-processing company (state-run at the time of my stay) dominated areas such as employment and all municipal and political issues. The year of my stay in Bor was supposed to be the final year of the smoke.

Heroic endurance under the smoke was a strategy that Borani used to negotiate the stigma of the toxic exposure of their town. People used this strategy to deal with their feelings of powerlessness to do anything to change the situation. And the ‘situation’ was not easy. The beginning of effective work of the new smelting factory, which was being built during the time of my fieldwork, was completely uncertain, and many people regarded the project to be politically corrupted. The exact consequences on people’s health were unknowable, as the state institutions could not monitor and provide information about the long-term impact. “Sve se ne zna” people would say, or “It’s absolutely known that nothing is known”.

I think “stuckedness” here is very useful for thinking about Borani’s endurance under pollution. Contamination and a rising precariousness and a condition of unknownability significantly shaped their world.

The šmekerski character of the smoke, mentioned at the beginning, and a feeling of stamina that people felt, brings to mind what Ghassan Hage calls the “heroism of stuckedness”, and a “celebration of survival” (Hage 2009: 101) which he developed in his research on transnational Lebanese migration and white racists in Australia. Hage identified this kind of sentiment as a contemporary condition in his research on yearnings for existential mobility which offered to his informants an imagined or felt movement of “moving well”. The latter served people to avoid the feeling of existential immobility (Hage 2009: 98), and led to a particular sense of “stuckedness” (Hage 2009: 97). “Stuckedness” was opposed to “going somewhere” as a future-oriented movement (and not just a particular status), “a social capacity, enhanced by sociality” (Jansen 2015: 52). Hage argued that the social and historical conditions of permanent crisis led to the proliferation and intensification of the sense of stuckedness among his informants. Rather than being perceived as something one needed to escape at any cost, the stuckedness simultaneously coexisted with a feeling of “an inevitable pathological state which has to be endured” (Hage 2009: 97). According to him, “stuckedness in crisis” could be transformed into an endurance test: a crisis was confronted by a celebration of one’s capacity to “stick it out” rather than calling for change.

I think “stuckedness” here is very useful for thinking about Borani’s endurance under pollution. Contamination and a rising precariousness and a condition of unknownability significantly shaped their world. Many of my interlocutors were “waiting out” (Hage 2009): for polluting conditions to finally end, for the state to do something about it, for the new smelting factory to start working and so on. The heroic celebration of endurance under the smoke refers exactly to “a subjection to the elements or to certain social conditions and at the same time a braving of these conditions” (Hage 2009: 102).

However, in contrast to Hage who uses the feeling of “stuckedness” to explain a sense of “not moving well”, the ability to stick it out, šmekerski, with dignity and pride in the polluting setting which was not of people’s choosing became domesticated as a significant marker of a particular “mode of life”, a lifestyle that contained much of irony. Even though this strategy perhaps did not enable Borani to feel that they were “going somewhere”, such a sense of stamina and heroic endurance under pollution did enable them to grab some agency “in the very midst of its lack” (Hage 2009: 100).

Smoke in Bor was so powerful that it conveyed and awakened various kinds of affects among the people – from proud endurance under the smoke to fear of potential risks and hopefulness (Jovanović 2016). After all the things the citizens of Bor have lived through, including the downfall of copper industry, of their town and a rapid decline of living standard after 2000, I believe that it was no coincidence that my friend from Bor called his co-citizens ‘Borci’ (‘Fighters’) instead of ‘Borani’. For the people of Bor, the heroic endurance under the smoke was one of many social practices entangled with the smoke through which people made their life tolerable, dignified, creative, poetic and even amusing in the midst of their troubles.

Youtube video footage from June 2015,showing the smoke falling down in Bor, used with permission of the author.

References

Hage, G. (2009). “Waiting out the crisis: on stuckedness and governmentality.” in H. Ghassan (ed), Waiting. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp.97-106.

Jansen, S (2015). Yearnings in the Meantime:’Normal Lives’ and the State in a Sarajevo Apartment Complex, Oxford, New York: Berghahn Books.

Jovanović, D (2016). “Prosperous pollutants: bargaining with risks and forging hopes in an industrial town in Serbia”, Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology. DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2016.1169205

Radulović, M. (1987.). Priča o mom gradu [The story about my town]. Bor: Radna organizacija Štampa, radio i film.

Deana Jovanović is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies of Southeastern Europe at the University of Rijeka (Croatia). Deana holds a PhD in Social Anthropology (the University of Manchester), and she researches urban, political, and environmental anthropology. Her research focuses on anticipations of futures in deindustrialised and reindustrialised urban environments across East Europe.

[1] Šmeker refers to a person, usually male, who is charming, well-mannered and sometimes flirty, handsome and stylish.