India Holme, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick

“When it comes to sustainability, 2016 will be a year of distraction, fear and disruption. Around the world, a host of economic and political threats – including the refugee crisis, terrorism and teetering markets in Europe and China – will continue to crowd headlines… long term environmental destruction is likely to get pushed to the back burner of global consciousness. When people feel threatened and insecure, they generally turn to shorter term thinking and deprioritize pro-social behaviour. For consumers, this means corporate social responsibility (CSR) will simply not continue to drive buying decisions at the same level that it has in previous years.” (Jonah Sachs, the Guardian, 23rd December 2015)

With terrorist attacks, Brexit, the inquiry into the Iraq War and a plethora of other ‘big’ news causing concerns for citizens world-wide; I share Jonah’s fear that the collective ‘we’ of 2016 and the ‘we’ of the future are just too preoccupied with more immediate and terrifying threats than whether or not our pizza box can be recycled[i] and the sustainability life-cycle of our plastic water bottles.

I too have been wrapped up in Brexit and the fall out that has followed, with concerns for migrants, society, the British economy and the environment. But persistently, no matter the headlines, I now consider the consumer waste we create in a new light. However, this light doesn’t fill me with a warm, fuzzy glow – it fills me with questions and concerns.

Take the plastic water bottle, a long-term sustainability ‘baddie’ but one that I do sometimes use and recycle. I want the bottle to be recycled, but I, like many of us, rarely check that it can in fact be recycled. If it can’t be recycled, then how long does it take to decompose in landfill? And if it doesn’t go to landfill then where does it go? If it’s going to be incinerated then how damaging is this item, I am purchasing, to the environment? And to human health?

These questions now flood my mind on a daily basis. I have re-usable drinks flasks and spend ages scrubbing remnants of food from jars and shampoo dregs from bottles. But what if I could easily and affordably purchase greener items in the first place. A plastic tomato ketchup bottle that will one day form part of a children’s play area? A tin can that has been formed by tin cans and will form other tin cans forever more? This is where I feel frustrated. I want to be a responsible consumer, I would like to be part of a green economy[ii] and I agree that a circular economy is better for the environment; but I also feel ‘we’ as consumers are somewhat left in the dark when it comes to making more sustainable purchases and decisions.

I believe that if we made the process of selecting more environmentally friendly products as easy as possible, whilst ensuring people are aware of the earth’s future peril, that many more people would become proactive in the fight against climate change, even if this everyday ‘activism’ is popping alternative choices into their shopping trolleys, wasting less and recycling more.

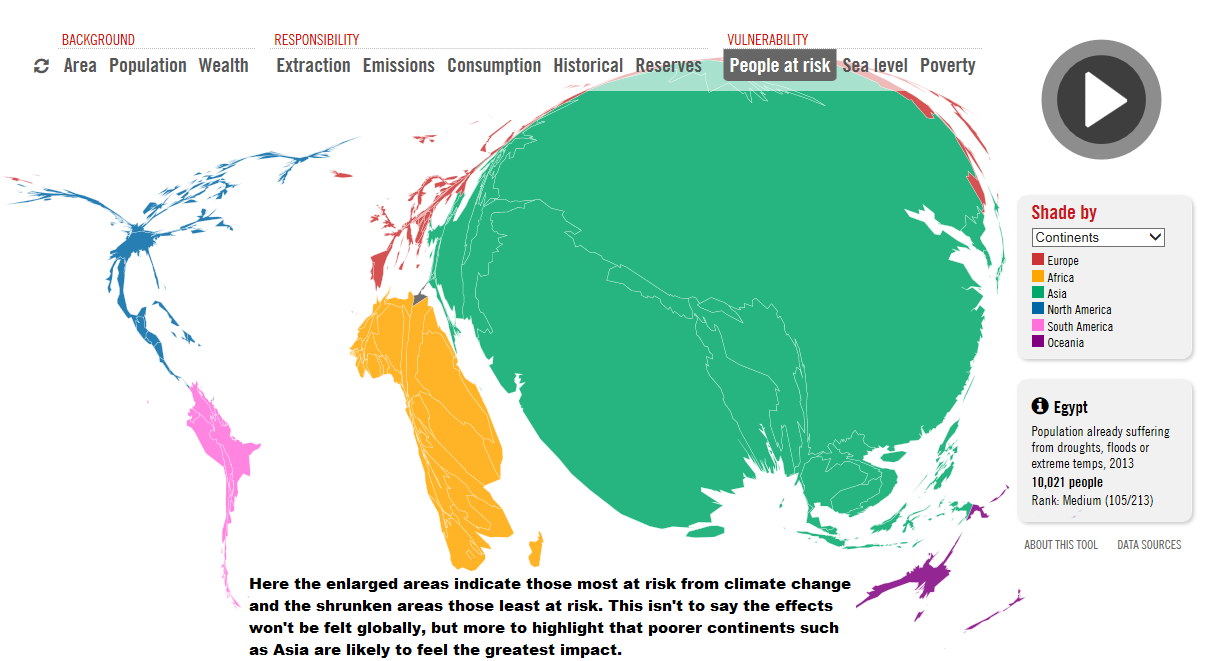

If we continue to consume carbon at the rate that we are, by 2100 the world would be a completely different place.

For many people not well versed in the consequences of climate change or as I sing in my head… ‘It’s the end of the world as we know it…’ this ‘climate change theme tune’ may appear dramatic. But the situation is dire. If we continue to consume carbon at the rate that we are, by 2100 the world would be a completely different place. The production and materials involved in packaging our consumer goods contributes to this problem since they nearly all depend upon carbon . Arguably we are already feeling the consequences of these rising temperatures and things are only going to get worse. It is the poorest regions of our beautiful planet that will be hit the hardest, despite the residents of these afflicted areas having contributed far less to global carbon levels.[iii] The tonnes of annual carbon consumed (from goods and services) per person in developed countries can be high as 16.6 in the USA and 14.7 in Australia yet as low as 0.4 in developing countries like Bangladesh. The below fantastic interactive map simplistically shows a wealth of information regarding climate change, emissions, poverty and risk etc.

If climate change isn’t the most glaring example of environmental injustice, then I don’t know what is.

“The challenge of climate change is the management of potentially great risk to the lives and livelihoods of humankind over the coming century and beyond, whilst at the same time overcoming deep poverty, in all its dimensions, in the next two or three decades.” (Stern, 2015)

I wholeheartedly agree with Naomi Klein when she says we need to get proactive ‘as the door to reach two degrees is about to close. In 2017 it will be closed forever.’[v] The climate change situation is extreme. So given the extreme situation we are in; why am I banging on about eco-labels and product information? Clearly this isn’t going to ‘save the world’, but the fight against climate change needs a vast arsenal of weapons. One of these weapons can be reducing the number of products we consume that have carbon footprints on the higher end of the scale whilst increasing the number of sustainable products we purchase AND re-using and recycling far greater percentages of these products than we currently are doing.

So given the extreme situation we are in; why am I banging on about eco-labels and product information? Clearly this isn’t going to ‘save the world’, but the fight against climate change needs a vast arsenal of weapons.

The Sustainability Consortium (TSC), has recently published its first impact report on ‘Greening Global Supply Chains; From Blind Spots to Hot Spots for Action’. The Executive Summary states:

‘Global production and use of consumer goods accounts for more than 60 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, 80 percent of water usage, and two-thirds of tropical forest loss globally. With 2.5 billion more people joining the consuming class in the next few decades, we must address the production, use, and disposal of consumer goods: a sustainable world requires sustainable production and consumption.’

There are many elements involved in the production of consumer goods, upstream supply chains at the initial stages of the products life-cycle, manufacturing, transportation etc. all the way to downstream chains, where it reaches the shelf, the consumer and then exits the consumer’s life and goes off to landfill, incineration, recycling plants and so on. Packaging is just one element of this and as TSC notes:

‘Reduction in packaging represents cost saving and a reduction in environmental impact visible to customers, which may explain why we see greater awareness and action around sustainable packaging opportunities than other impact areas.’ (2016 Impact report, p. 37)

As packaging faces the consumer, this is the ideal place to tell consumers that sustainability matters. If whilst shopping we are surrounded by packaging clearly telling us about its environmental sustainability, alongside our exposure to huge national government/NGO campaigns informing us of the effects of climate change and the need to behave and shop more sustainably then hopefully we will listen.

Sustainable packaging and recycling will make a difference to climate change. Recycling saves energy (energy produced by burning fossil fuels) because the manufacturer doesn’t have to produce something new from raw materials, it reduces landfills, it is good for economy because recycling and purchasing recycled products creates a greater demand for these products which use less water, create less pollution and use less energy.

If we are going to keep consuming then let’s at least consume products that can form part of a green circular economy.

When it comes to the issues of recycling and sustainable products that the efforts to create a better world need to come from ‘above’ and ‘below’ … ‘at all societal levels’, from government intervention and regulation, corporate responsibility and consumer demand. If we are going to keep consuming then let’s at least consume products that can form part of a green circular economy. We need to demand more products like this and much clearer information so that we can (very) easily make more sustainable choices.

Yet, when it comes to packaging a recent study found the majority of 1500 respondents from India, Sweden and the US ‘see major problems with society’s consumption of packaging’. Frustratingly, companies are still claiming that in many instances:

‘Encouraging customers to make sustainable choices is proving to be one of the most difficult environmental challenges for businesses in the twenty-first century.’ (Carbon Trust, November 2014)

This could partly be due to the reason that ‘while nutrition information is relatively standardised, sustainability information comes in a plethora of different forms with more than 100 different schemes available in the EU alone.’ (Peter Burgess, Head of Consumer and Sensory Sciences, Campden BRI, November 2015). As to the standardised nutritional information Berguess refers to, I love the traffic light system on food; red, amber, green, fat, sugar, salt – easy-peasy. Even with a screaming toddler and a mardy five year old I can glance at that and see that sauce ‘A’ is all red and ‘B’ is mostly green and amber; so in goes the latter and the former sits waiting for a less scrutinising shopper. But what about the jar itself? Is it glass? Well that should be ok… shouldn’t it? They can smash that up and make some new jars. Or perhaps its plastic… is it ‘good’ plastic or ‘bad’ plastic? Too much to consider in the blink of an eye on a mad shopping dash. So I consider it at the end point, as it exits my house and then I am filled with consumer guilt, is this going to wash up in pieces on the coast? Be burnt and pollute the air? Or sit in a hole for 500 years…?

Is there in fact some simple symbol I can look for on products that is related to the products lifecycle but I just don’t know about it? No, there isn’t. There are many symbols as Burgess mentioned, they are complicated and small and often quite hard to find. Unless you can memorise the meaning of each of them, I don’t believe they are that much use at all. TSC’s Impact Report also highlights the abundance and complexity of eco-labels: over 450 with over 200 different ecological, ethical, or sustainability attributes for food, and over 30 symbols and labels just for the natural and organic cosmetic products alone (2016 Impact Report, p. 20). The main reason for this is that ‘they have been developed relatively independently of one another and thus are not aligned around materiality or measurement standards’ (2016 Impact Report, p20).

As a good ‘millennial’ I decided to consult a couple of community groups on Facebook and ask people’s views on packaging and sustainability with reference to the traffic light system. Some people commented that a very clear system would ‘make them think twice about purchasing things’; would ‘tempt’ them ‘to buy the environmentally friendly product… (as they) always make choices based on advice on packaging i.e. eggs (free range) tuna (how fished) etc.’. The overall consensus was that it would ‘influence’ people when shopping. Others commented that ‘until manufacturers are made to pay we have little chance on making the big impact required’ and ‘it would just be better if it were enforced for all companies to use the packaging with the least time to biodegrade’, whilst a couple of people suggested huge reductions in packaging/no packaging. This led to some interesting ‘Googling’ of my own and whilst it isn’t something I can cover here there are some great articles about package free shops.[vi] However, people’s comments did reassure me that this is something (some) people care about and that it could hopefully change consumer habits, and as some people highlighted it could then change manufacturing ‘habits’.

The Carbon Trust argues that ‘companies need to use the full marketing and advertising arsenal at their disposal to encourage consumer uptake of sustainable products. Branding, packaging, promotion, and placement all have to be effectively deployed. These are well-proven techniques that are known to work.’ (November 2015, accessed 06/07/2016).

Clearly we like to buy ‘stuff’, so let’s start buying environmentally and socially ‘better stuff’.[vii] I agree with Andy Ridley, the founder of WWF’s Earth Hour, that ‘a longstanding problem for the sustainability movement is that it’s tended to demand we stop this or that rather than offer attractive alternatives’. The circular economy, however, isn’t saying we should stop consuming, it’s saying we should start consuming differently’ (the Guardian, 28/06/2016).

‘The choices we make when we are shopping are very important, particularly when it comes to the types of packaging we select with the goods we buy. By consciously favouring packaging that has been manufactured in a sustainable way from materials that can be renewed or recycled, we send an important message back to the manufacturers, a message that will influence their future actions. Packers, in turn, need to provide the information that consumers need to make these informed choices.’ (Ebro Color: success through packaging)

Encouraging consumers to choose more sustainable products and making it easier for them to do so has so many positive outcomes.

Surely we can come up with something better than what we have at present. Governments, NGOs, consumer groups and industry need to work together to create something meaningful. Encouraging consumers to choose more sustainable products and making it easier for them to do so has so many positive outcomes. According to a report by PWC, this is good for business profits, the economy and great for combatting climate change; greening production lines and greening the economy can also help to create between 15 and 60 million jobs (report by UNEP).

We need some help to consume differently on a mass scale. We need clear, simple information, we need to be made aware of the threat of increasing climate change and how it effects the planet and our lives. And we need:

“… a verifiable, understandable, and authoritative “nutrition label” for green. Until the appearance of the nutrition label on store shelves, you’d rarely find shoppers poring over the back of that box of cereal trying to figure out if it was good for little Timmy’s tummy. But once the standards were put in place, consumer behavior changed to accommodate the new trustworthy comparative data. The same thing will happen with green.”[viii]

If we combine meaningful nutrition style labels, a government campaign about climate change and use some ‘cultural manipulation’ then maybe eco-labels could make a difference. David Korten argues in his Agenda for a New Economy that,

‘Corporate advertisers and public relations propagandists have mastered and professionalized the arts of such cultural manipulation, particularly through corporate-controlled mass media.’[ix]

…imagine if governments and industry ensured that ‘doing’ something was as simple as possible? As simple as buying ‘this’ instead of ‘that’ and popping the 100% recyclable packaging in ‘this’ bin instead of ‘that’ one.

Imagine if this mastery was put to telling us all about climate change [x]and what we can do? And imagine if governments and industry ensured that ‘doing’ something was as simple as possible? As simple as buying ‘this’ instead of ‘that’ and popping the 100% recyclable packaging in ‘this’ bin instead of ‘that’ one. Imagine if consumers knew more about climate change and demanded more sustainable products that support the green economy. Imagine if doing this created a better, healthier environment. Imagine if creating a simple, at a glance, yet meaningful ‘sustainability accreditation system’ meant that more people shopped sustainably. Imagine if this change, combined with many other changes meant we (as in the global ‘we’) could keep a 1.5 degree warming. I can imagine it. I think that collectively the world can reduce the rate of global warming … if ‘we’ act now. If ‘we’ change our habits now. And if by ‘we’ – we mean everyone, from the North to the South, from the corporate boards to the manufacturing lines, from the producer to the consumer.

(Featured image credit: MJonty, Flikr)

[i] The answer to whether or not we can recycle pizza boxes is a resounding ‘no’. Any paper, cardboard or polystyrene that has come into contact with any food (even if it has been cleaned) cannot be recycled as the oil from the food soaks into the paper fibres and cannot be dissolved. This includes frozen food containers where the food has been protected in additional wrapping, e.g. the frozen vs. take-away pizza box. Whilst we may assume the box has been protected from the oil the box itself is coated in a plastic polymer to prevent freezer burn and this means the boxes are not recyclable or compostable.

[ii] Defra describes the green economy as ‘where economic value and growth is maximised while managing all natural assets sustainably. Achieving a green economy means the transformation of the whole economy in terms to what is produced and used, who produces and uses it and how it is disposed of.’ The Economics of Waste and Waste Policy (June 2011, p. 6)

[iii] Miranda et al, (2011) ‘The Environmental Justice Dimensions of Climate Change’, Environmental Justice, Vol. 4, No. 1. See also, Union of Concerned Scientists – ‘Each Country’s Share of CO2 Emissions’ (accessed 06/07/2016)

[iv] A lecture by Nicholas Stern entitled ‘Environmental justice and climate change’ delivered at the International Meeting on Environmental Justice and Climate Change Istituto Patristico Augustinianum, Rome 10-11 September 2015.

[v] Naomi Klein, ‘This Changes Everything’ (2014) p. 23

[vi] See, e.g., Packaging-free shopping on the rise in Europe; Germany’s first waste-free supermarket about to open its doors; List of Packaging-Free Shops.

[viii] Freya Williams and Graceann Bennet, (2011) ‘Mainstream Green’, The Red Papers, Ogilvy & Mather, p.63

[ix] David C. Korten, ‘Agenda for a New Economy’ (2010)

[x] Coincidentally, during researching this piece the BBC and the Guardian have reported more fervently on climate change. However, we know from various studies that overall ‘climate change’ reports in the media are lacking, in particular in developing countries, see John O. Kakonge’s Global Policy Essay, (November 2011) ‘The Role of Media in the Climate Change Debate in Developing Counties’. An excellent resource for considering the media coverage of climate change is provided online by the University of Colorado.