Dr Olga Kuchinskaya, Assistant Professor, Department of Communication, University of Pittsburgh

The main question about the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident, as historian David Marples puts it, is “how many people did it actually affect through death, illness, or evacuation?” My book, The Politics of Invisibility: Public Knowledge about Radiation Health Effects after Chernobyl, suggests that this question might have become impossible to answer.

My research began in 2003, when somebody asked me about the number of Chernobyl’s victims. That was when I discovered the 2000 report of the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, which argued that the only health effect for the general population was an increase in thyroid cancer in children. A similar position was reiterated a few years later in a September 2005 joint press release by the International Atomic Energy Agency, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations Development Programme. According to that press release, “fewer than 50 deaths had been directly attributed to radiation from the disaster, almost all being highly exposed rescue workers.”

Along with the UNSCEAR report, I read Voices from Chernobyl (1999) by Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich, who collected oral histories about the experience of Chernobyl in Belarus, the former Soviet Republic that received much of the fallout from the accident. (Svetlana Alexievich has since been awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature). Two quotes in particular struck me; both reflected on radiological contamination as entirely imperceptible with the unaided senses. Alexievich writes:

Something occurred for which we do not yet have a conceptualization, or analogies or experience, something to which our vision and hearing, even our vocabulary, is not adapted. Our entire inner instrument is tuned to see, hear or touch. But none of that is possible. In order to comprehend this, humanity must go outside its own limits.

A new history of feeling has begun. (1999, 20).

The second quote, from a monologue of an older woman who lived in the heavily affected area, doubted the reality of the imperceptible contamination:

What’s it like? Have you seen it in the movies? Have you ever seen radiation?

What colour is it, white? Some say it’s colourless and odourless, others that it’s black. Like the earth. And if colourless, then it’s like God. God is everywhere, but no one can see him. They’re just scaring us! […] I don’t think there ever was any Chernobyl, they just made it up. Tricked people. (1999, 45).

The question of reality of what is happening with radiological contamination is noted by Ulrich Beck in the context of the immediate aftermath of Chernobyl in Europe. Beck observes that “nothing has changed for the eyes, nose, mouth, and hands” and yet “[t]he foundations of life have changed, even if everything appears to have remained the same” (Beck attributed the success of his Risk Society (1992[1986]) to this “anthropological shock” after Chernobyl (1995, 65)).

I was puzzled by how we learn about effects of imperceptible hazards when even the most affected groups, including those who have been living in the affected areas for decades, cannot rely on their senses, and when health effects are not immediate. Reading Alexievich alongside various reports on Chernobyl led me to the two questions in my research: How have we come to know what we know about radiation health effects after Chernobyl? And, what social mechanisms guarantee that this knowledge is adequate—that is, socially just? Radiological contamination after Chernobyl affected millions, and recognition of the people’s past suffering—as well as prevention of future suffering—is a matter of social justice. This could be illustrated with another quote from Alexievich’s book, where a boy in a hospital setting counts children he knew who died:

Yulia, Katya, Vadim, Oxana, Oleg. Now Andrei. ‘We will die and become science,’ Andrei said. ‘We will die and be forgotten,’ Katia thought. ‘We will die,’ Yulia wept. For me the sky is alive now when I look at it. They are there. (1999, 182).

What social mechanisms guarantee that victims of Chernobyl are not simply forgotten?

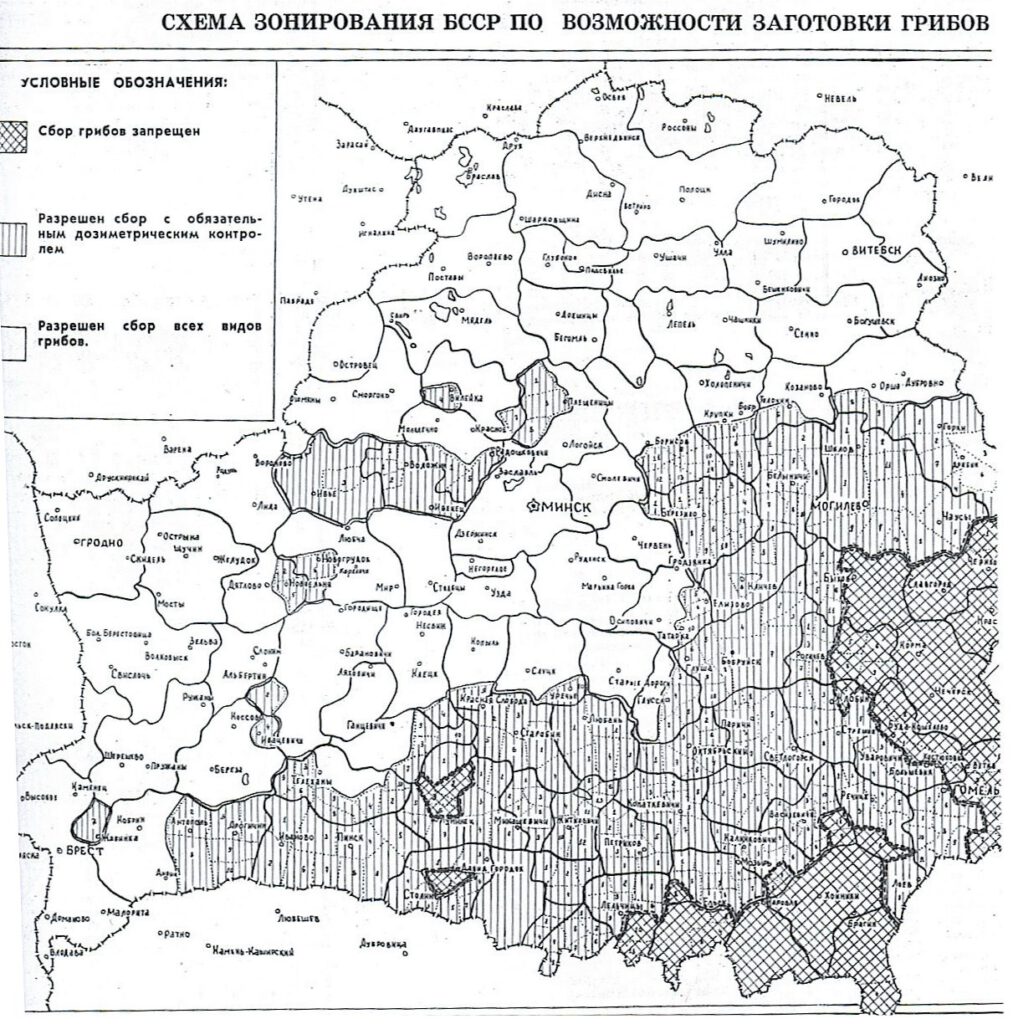

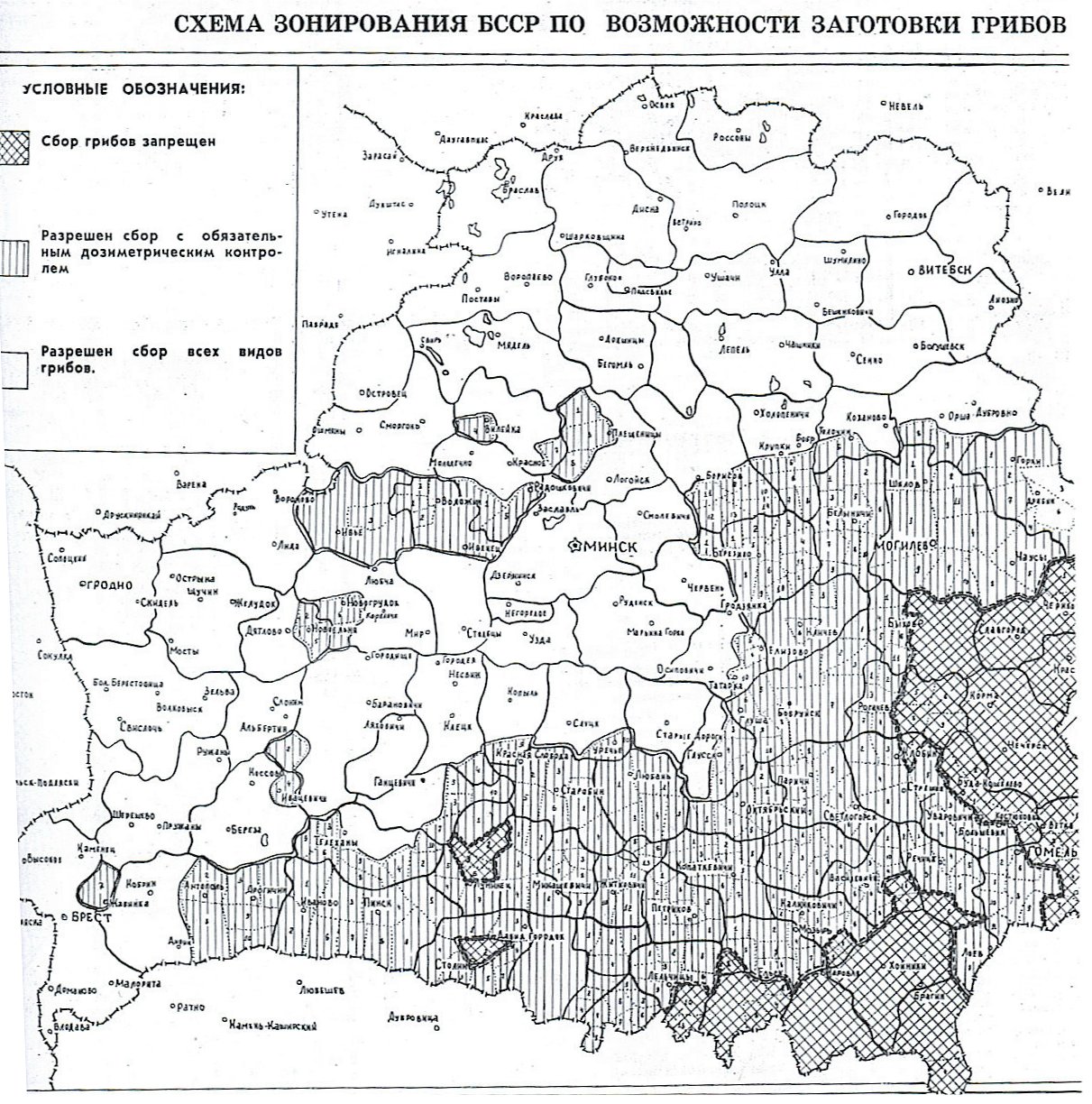

My analysis in The Politics of Invisibility was based on the insight that because radiation is imperceptible, one’s experience of it is always mediated. Our experience of imperceptible hazards is always necessarily mediated with measuring equipment, maps, and other ways to visualize it, but also with narratives. How these representations are produced matters. Different ways of representing “Chernobyl” can make radiation and its health effects observable and publicly visible, or, on the contrary, unobservable and, by extension, publicly non-existent.

Based on archival and ethnographic research in Belarus, the book describes the production of invisibility of Chernobyl’s consequences—that is, representation practices and institutional or infrastructural conditions that displace radiation and its health effects as an object of public attention and scientific research, and make them impossible to observe. As a result, links between radiation exposure and its health effects are not constructed; the “consequences of Chernobyl” dissolve into individual health problems of unspecific origins. This production of invisibility can be thought of as the opposite of the discovery of microbes. (Imperceptible to our senses, germs did not exist as socially recognized actors prior to Pasteur’s experiments; they had to be made publicly visible.)

Making invisible hazards visible is work; it requires significant effort.

Making invisible hazards visible is work; it requires significant effort, including when they are as massive as post-Chernobyl radiological contamination. At the same time, this is not a one-way process: imperceptible phenomena can also be made publicly invisible. To somewhat oversimplify, I demonstrate that the consequences of Chernobyl in Belarus become unrecognized as a result of redefining the scope and nature of these consequences, as well as reshaping research and protection practices.

The Politics of Invisibility demonstrates vast historical fluctuations in recognizing the consequences of Chernobyl in Belarus. Invisibility came in waves; there was a period, beginning about three years after the accident, when radiological consequences were made amply visible in Belarus, before gradually disappearing in the late 1990s. I argue that these waves of in/visibility are a function of power relations. They are shaped by the historically shifting power imbalances and efforts to reveal or conceal Chernobyl’s consequences as they were undertaken by various affected populations, scientists, media, the Belarusian government, and international organizations.

The public disappearance (lack of recognition and articulation) of the consequences of environmental contamination is not necessarily unique to this Belarusian case. Many hazards, including those in Western contexts, are continually obfuscated by industries that produce them, aided by administrative bodies that do not regulate them (Hess 2007, Langston 2011, McGarity and Wagner 2010, Michaels 2008, Murphy 2006, Oreskes and Conway 2010, Proctor 1995, Proctor and Schiebinger 2008). What stands out in case of Chernobyl is visibility of radiological contamination in the last years of the Soviet Union, with corresponding media coverage, the passage of laws, and the establishment of research institutes.

Sometime after the book came out, I was contacted by a Japanese-American physician who was concerned about radiation protection efforts and estimating radiation health effects after Fukushima. She connected with researchers in different countries, questioning them in what could be described as a quest for objective knowledge. She was concerned about expert positions that appeared too “alarmist” and simultaneously worried about “systemic dismissal” of potential radiation health effects; the truth, she assessed, would have to be “somewhere in the middle.” Thirty years after Chernobyl and five years after Fukushima, the questions about the truth on Chernobyl’s consequences—the number of victims, conflicting assessments of radiation health effects—persist.

To make any conclusions about Chernobyl’s consequences, we have to ask about the social conditions that affect the production of knowledge: what kinds of research were done (and not done)? This is the question about conditions for scientific research, but also about resources and opportunities available for the affected populations, activists, and civil organizations. This focus on conditions for generating evidence reminds us that, as with other environmental exposures, the lack of evidence does not necessarily mean the absence of effects.

Dr Olga Kuchinskaya is author of the book ‘The Politics of Invisibility: Public Knowledge about Radiation Health effects after Chernobyl’ (2014: MIT University Press). Her research interests include questions regarding the production of knowledge and ignorance about environmental hazards, especially imperceptible threats that require scientific expertise and tools to establish them as hazards in the first place.

References

Alexievich, Svetlana. 1999. Voices from Chernobyl: Chronicle of the Future. London: Aurum.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992 [1986]. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Beck, Ulrich. 1995. “Anthropological Shock: Chernobyl and the Contours of the Risk Society” in: Ecological enlightenment: essays on the politics of the risk society. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, p. 63-76.

Hess, David J. 2007. Alternative Pathways in Science and Industry: Activism, Innovation, and the Environment in an Era of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Langston, Nancy. 2011. Toxic Bodies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

McGarity, Thomas O., and Wendy Wagner. 2010. Bending Science: How Special Interests Corrupt Public Health Research. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Michaels, David. 2008. Doubt Is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Murphy, Michelle. 2006. Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. 2010. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Proctor, Robert, and Londa L. Schiebinger. 2008. Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Proctor, Robert. 1995. Cancer Wars. How Politics Shapes What We Know and Don’t Know about Cancer. New York: Basic Books.

United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). 2000. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation. Report to the General Assembly, with scientific annexes. New York: United Nations.