Professor Gabrielle Hecht is based at the Department of History at the University of Michigan, where she has also directed the Program in Science, Technology, and Society. She has authored several award winning books about ‘nuclear things’.

My obsession with nuclear things began as a teenager. In 1978, my family moved to Zurich, where for two years we rented a suburban home. Following Swiss law, the house had its own fallout shelter in the basement, complete with a thick lead door. We never talked about this room, any more than we talked about the rifle that my father kept in the attic, issued to him as a member of the Swiss army reserve. Both reflected the fears of a landlocked nation. Squeezed between the shelter and the rifle, surrounded by mountains, I sometimes found it difficult to breathe.

Perhaps sensing my need for broader vistas, my English teacher introduced me to the beautiful, terrifying worlds of science fiction. In short order, I came upon Walter Miller’s masterpiece, A Canticle for Leibowitz. Set centuries after a devastating nuclear war, the novel opens with a monastic order whose mission is to preserve and illuminate the remnants of scientific texts, including a blueprint signed by a soon-to-be-sainted engineer named Leibowitz. Gangs of mutants attack travellers who dare make their way across the desolate terrain of North America. By the book’s end, humanity reinvents the bomb and stands poised, once again, on the brink of self-destruction. I was not reassured. But I was compelled.

Like many children of the Cold War, I had recurring nightmares set in grey landscapes that merged the bleak deserts of Leibowitz with iconic images of a devastated Hiroshima.

In 1980, we moved back to Paris, where I completed high school. No more fallout shelter, no more rifle… but the Cold War was heating up again. Presidential elections flipped national politics: conservative Ronald Reagan in the US, socialist François Mitterrand in France. The Solidarity movement took Poland by storm, capturing European imaginations and alarming the Soviet Politburo. School officials feared a Soviet invasion of Poland and cancelled our class trip to Leningrad. But don’t worry, said the adults. Nuclear deterrence will prevent another world war. That didn’t help. Like many children of the Cold War, I had recurring nightmares set in grey landscapes that merged the bleak deserts of Leibowitz with iconic images of a devastated Hiroshima.

Fast-forward to 1989, my fourth year of graduate school. Two months before the Berlin wall began to crumble, I found myself back in Paris, finally about to research the nuclear world on my own terms. Well, almost. I’d initially wanted to write about weapons, but soon learned that was archivally impossible. But my project on the history of French nuclear power offered a back door. France’s civilian and military programs were intermeshed. Yet the myth of their separation was just — barely — strong enough as to make the civilian program researchable.

Emphasis on “barely.” Official archives were closed. France had a “dérogation” system by which researchers could request permission to consult documents. But that avenue was closed off to me: “We deeply regret, mademoiselle, that we have not yet catalogued our papers.” You can’t apply for permission to consult documents that don’t even appear in finding aids.

I needed a back door to the back door. I decided to interview old-timers in the nuclear industry. My letters of inquiry stayed well away from politics, instead framing my project in terms of simple technological history. The very first interview I scored was with a top executive at Electricité de France (EDF), a man who’d been the project engineer for six gas-graphite reactors. My pulse raced and my hands trembled as I entered his gigantic office. Taking a deep breath, I followed my script. Could Monsieur le directeur please tell me about the technical and scientific decisions he’d made in the 1950s and 1960s? He roared at me, pounding his desk. Non, mademoiselle! These were not scientific or technical decisions! They were economic decisions! Political decisions! The volume of his voice notwithstanding, my pulse returned to a normal rhythm. I was in business.

To be sure, Monsieur le directeur was exceptional. He still passionately believed that EDF’s 1969 decision to abandon its gas-graphite design in favour of US-designed light water reactors was wrong. What better messenger for posterity than a historian who would record his thoughts? But what really made him exceptional was his generosity. He’d kept meters of historical documents about the gas-graphite program, neatly arranged in his office. He let me return time and again to consult these. He facilitated dozens of other interviews, as well as visits to reactor sites, where I found many more documents stashed in metal closets. No finding aids, no archivists – but plenty of state-of-the-art photocopy machines.

Whatever you think about the industry as a whole, remember that most of its people are just like you: they work hard, recognize their responsibilities, and honestly believe they’re doing the right thing.

Not everyone was so open. Several of my interlocutors scolded me for focusing on the wrong topic. Some told blatant lies. There had never been any conflict among French nuclear institutions, insisted one pair. Another maintained that EDF had never produced weapons-grade plutonium, an assertion directly contradicted by documents and other interlocutors. One retiree tried to ask me out (that was creepy — I was 24). But the vast majority of my interlocutors spoke in good faith, summoning memories as best they could, sharing whatever documents they had. Whatever you think about the industry as a whole, remember that most of its people are just like you: they work hard, recognize their responsibilities, and honestly believe they’re doing the right thing. Although I did not hold back on unpleasant facts, I tried to convey this sense in The Radiance of France. Perhaps that’s one reason why it was well received in French nuclear circles.

That, and the fact that I didn’t discuss health and environmental issues. At all. Because, you know, there’s a limit to openness. And that material was most definitively not accessible in France – at least, not by any subterfuge that my twenty-something self could imagine.

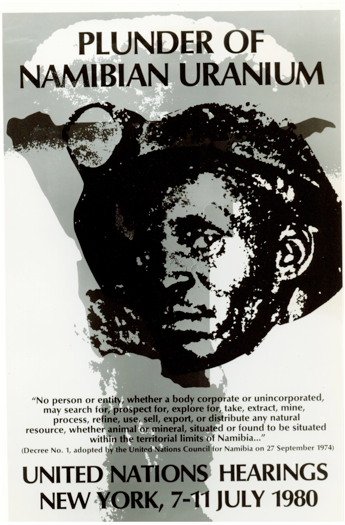

In my second project, I sought other ways into such material. My initial goal was to rethink the “nuclear age” from a colonial and postcolonial perspective by examining the history of uranium production. I knew official archives would not bring much joy, but I had to try. French archives yielded little. By contrast, Britain’s National Archives hold an enormous collection of uranium-related files, most of it readily accessible. Yet these documents said little about many of the things I cared about – labour, worker health, African perspectives.

Back to back doors, site visits, and interviews. Which, to be honest, is a lot more fun than sitting in a reading room.

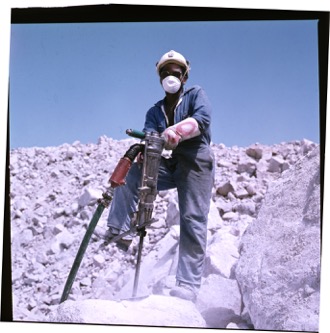

Over the course of many years, I visited mine sites in Gabon, Madagascar, South Africa, and Namibia. I interviewed workers, managers, engineers, doctors, and residents. I went underground into mine shafts and rode in the enormous haul trucks at open pits. I plugged my ears as I witnessed giant ore crushers, and tried to remain unfazed when acid fumes attacked my sinuses in yellowcake plants. I wandered through company towns, talked with people in their homes. I dug through closets and file cabinets and storage rooms in search of documentation. I offer a fuller account of this process in the appendix to Being Nuclear. Here, I limit myself to a few remarks about conducting research in Gabon and Namibia.

I went to Gabon in 1998. The country was still in the grip of its long-serving, megalomaniac president El Hadj Omar Bongo. Oppression and fear hung in the air, palpable in every conversation with Gabonese citizens.

The associate director of the Compagnie Minière d’Uranium de Franceville (COMUF), a Frenchman who’d spent his career in Africa, didn’t initially understand what I meant by “historical documents.” Eventually, though, he took me to a storage room filled with papers stacked every which way, some in boxes or binders, others in piles. Could that be what I meant? Yes! In that case, he said, failing to keep the incredulity out of his voice, we have two more rooms like this. Here are the keys. We’ll probably toss all this junk when we shut down next year.

Confronting an archive in deplorable condition produces a mixture of joy and despair. It’s exhilarating to see unprocessed documents, a relief not to be at the mercy of a bureaucrat. But the volume of material also induces panic. Where to start? I pulled out a file from the oldest stack I could find. Termite carcasses fluttered to the floor, followed by a cloud of fine dust as the document disintegrated in my hands.

Fortunately, most documents were in better condition. With my husband’s help (he’s also a historian – we were trading labour), I sorted through them as best I could, copying anything that looked interesting with a 35 mm camera. Promising threads would break midstream. I found radiation exposure reports for the late 1960s and early 1970s, and again for the early to mid-1980s, but material for other years never surfaced. This was the silence of chaos, born of the expectation that such records had no value.

Meanwhile, I interviewed long-time employees and residents. But they were suspicious. Who was I? What did I really want? Was I a spy for the government? For the French? Some men opened up; others didn’t. Some asked for help sending a family member to America; others just seemed happy to tell their story. Some talked freely as they toured me around; others sat stiffly in a room and confined themselves to answering my questions.

I interviewed long-time employees and residents. But they were suspicious. Who was I? What did I really want? Was I a spy for the government? For the French?

Jump to 2004, when I went to Namibia. It had been fourteen years since independence. Several men who’d been labour leaders at the mine in the 1980s were now in government. Once the iconic pariah of the liberation struggle, Rössing Uranium was now the development darling of the state.

Savvy about outside “experts” and their agendas, Rössing workers also questioned my motivations. But they were far more voluble than their Gabonese counterparts. Many openly criticized Rössing, even during interviews conducted on company property. After decades of liberation struggle, union organizing, and contacts with outsiders, outspokenness had become commonplace.

I was even more surprised at the openness of Rössing management. On the day I met him, the managing director led me to a well-lit room in the Swakopmund headquarters where hundreds of boxes were neatly arrayed on shelves. Board meetings, sales contracts, internal memos, operations logs, reports on labour unrest, and more were at my fingertips, no insects involved. Once again, I received keys to the archives. These were the records of a company that expected accountability.

I believe that the COMUF director gave me access to files because he couldn’t imagine that they contained anything of enduring relevance. I suspect that Rössing’s director gave me access because the company wanted to display increased transparency, and a foreign academic offered a relatively unthreatening means of doing so. And while neither place gave me access to medical records, archives in both had material on radiation and other sources of contamination — enough, when coupled with interviews, to piece together a substantial history.

“National security” is the mantra of the nuclear age, secrecy its reflex. In many places, it’s impossible to write nuclear history without finding back doors.

“National security” is the mantra of the nuclear age, secrecy its reflex. In many places, it’s impossible to write nuclear history without finding back doors. Once you do, nothing quite matches the thrill of finding a document stamped “secret.”

Yet we must always remember that archives – formal or not – are replete with silences. These stem as much from choices about what to preserve as from overt classification. Also: documents do not offer an unmediated window on events. In this respect, they resemble interviews. Both types of sources are products of their times and circumstances. Both make certain events visible while leaving others invisible. They are generated for particular audiences, and the stakes, spins, and nuances of their narratives are frequently difficult to discern.

That’s what makes it fun.

This essay is adapted from portions of Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade (MIT and Wits University Press, 2012) and The Radiance of France: Nuclear Power and National Identity After World War II (MIT Press, 1998 & 2009). Used with permission. You can find out more information about Professor Hecht and her work via this website and follow her on Twitter here.