Featured Image: A UNEP investigator assesses dozens of storage vessels for the toxic, carcinogenic and explosive missile fuel dimethylhydrazine that were abandoned by Soviet forces at a helicopter and scud missile base near Astana in Afghanistan. Credit: UNEP.

Doug Weir, Toxic Remnants of War Project

Armed conflict can generate significant levels of environmental pollution and is commonly associated with the collapse of environmental governance and oversight. Yet in comparison to civil or domestic sources of pollution, conflict pollution, and the behaviours that create or exacerbate it, are largely unregulated at present. This has serious implications for civilian communities affected by conflict and by military activities more broadly, as the environmental bootprint of the military is felt long before the first shots are fired. Can improved documentation help protect civilians and their environment, and modify the most polluting military behaviours?

Some background

With a few notorious exceptions, such as the aerial spraying of TCDD contaminated herbicides in south east Asia, the oil fires and depleted uranium ammunition in Iraq, or the US military’s use of burn pits, the toxic legacy of armed conflict is under-addressed by researchers, the media and the international community. This was one of the motivations for us launching the Toxic Remnants of War Project (TRW Project) in 2012, a project that examines the environmental and humanitarian impact of military and conflict pollution. By doing so, we hoped to contribute to the developing discourse over how the rules governing the environmental conduct of militaries in war could be strengthened.

Our interest in conflict pollution stemmed from many years of research and advocacy on depleted uranium weapons. By its nature, this is an issue that cross-cuts the environment and what is called humanitarian disarmament – a field promoted by NGOs, international organisations and progressive governments, that seeks to address a range of indiscriminate and inhumane weapons, most notably anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions.

Definitions matter in disarmament, so does your ability to define the humanitarian impact of a weapon, easy enough with a blast injury, less easy with radiological or toxicological exposures to an environmental contaminant.

Humanitarian disarmament generally addresses weapons that harm through explosive force, this meant that its vocabulary had been informed by the impacts, risk communication and advocacy approaches specific to these kinds of weapons. However armour piercing depleted uranium ammunition doesn’t explode. It burns but is not primarily an incendiary weapon, it is radioactive but not a radiological weapon and it is toxic but is not a poison or chemical weapon. Definitions matter in disarmament, so does your ability to define the humanitarian impact of a weapon, easy enough with a blast injury, less easy with radiological or toxicological exposures to an environmental contaminant.

It was therefore inevitable that we looked to the vocabulary of environmental risk to develop our case against the weapons. We talked about precaution, we talked about polluter pays and we talked a lot about civil radiation and environmental protection norms. None of which seemed to support the casual dispersal of uranium metal into the environment. It was equally inevitable that we then grew concerned about the other toxics in conventional weapons, the heavy metals, energetic materials, propellants and obscurants. Military research into the health risks from one of the proposed alternatives to depleted uranium helped bring this into particularly sharp relief, when a tungsten-nickel-cobalt alloy was found to produce aggressive tumours in rats (spoiler – it was the nickel and cobalt).

From the environmental impact of the production, testing, use and disposal of munitions it was just a short conceptual leap to pollution from the deliberate targeting of oil and industrial facilities, to the inhalational risks from asbestos and particulate matter in rubble, the collapse of municipal waste management, and the many and varied means through which conflict degrades environmental governance and oversight. All these sources of pollution were being discussed in isolation – we saw them as the toxic remnants of war.

Understanding the toxic remnants of war

For many of these pollution sources, what surprised us was the absence of data on their public health or environmental impact. Take conflict rubble, ubiquitous to conflicts but studies on the composition and distribution of particulates, on metals or combustion products are nearly impossible to find, as are studies that use air sampling to estimate potential doses. Take the residues from energetic materials or metals from conventional weapons; again data on real world use is almost wholly absent, with sampling restricted to the ideal conditions of firing ranges.

Does this matter? These are not just questions of academic interest. Conflicts are increasingly being fought in populated areas. In Syria, Gaza and Yemen, civilians remaining in or returning to these areas face potential exposures – not only to munitions residues and rubble but also to pollutants from damaged industrial sites. Similarly, military tactics like bombing oil infrastructure appear as popular today as they were in WWII and, such is our collective relief that we are not bombing civilians directly, we neglect to question the environmental consequences of these decisions and their short and long-term health risks.

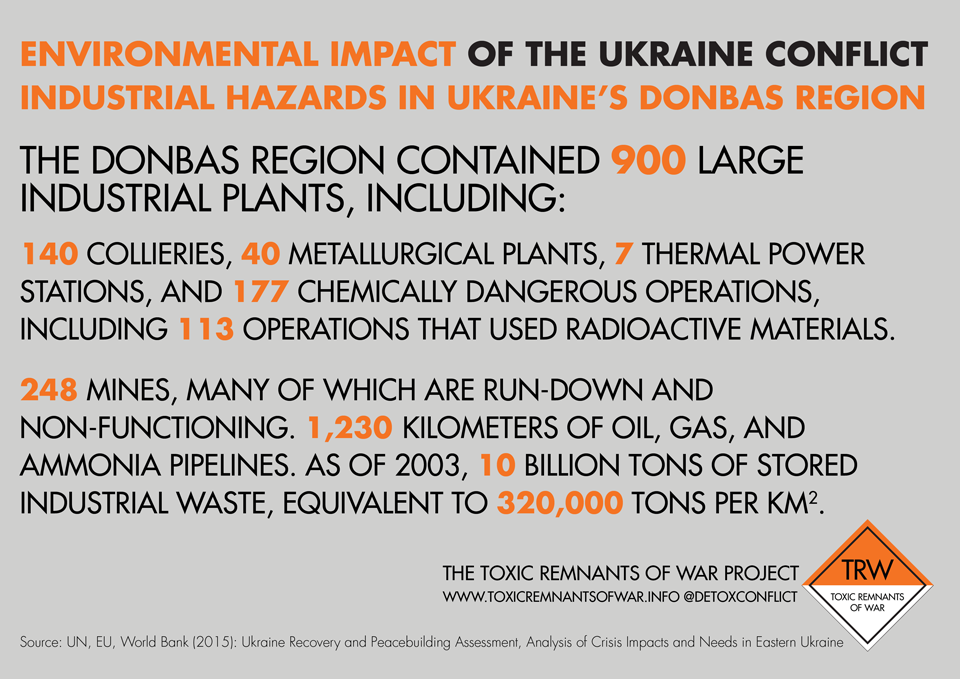

Increasing industrialisation means that conflicts are also being fought in areas replete with technological hazards. While much of the media footage from the Ukraine conflict showed green fields and sunflowers, the reality is that the Donbas region is one of the most heavily industrialised in the western world.

Increasing industrialisation means that conflicts are also being fought in areas replete with technological hazards. While much of the media footage from the Ukraine conflict showed green fields and sunflowers, the reality is that the Donbas region is one of the most heavily industrialised in the western world. A two hundred year history of coal mining, its attendant industrialisation and lax environmental regulation made the region a hugely risky place for a conflict. By 2003, it was estimated that 10bn tonnes of waste were stored in the region, amidst the 248 active and ageing mines and the 1,230km of oil, gas and ammonia pipelines. Power cuts to the region during the conflict caused pumps to fail in mines, and there are serious concerns about widespread groundwater pollution as a result.

Assessing pollution during and after conflicts

Following NATO’s 1999 decision to bomb petrochemical facilities in Yugoslavia and its use of depleted uranium, the precursor to what would become the United Nations Environment Programme’s Post Conflict and Disaster Management Branch was established to assess the environmental consequences of the conflict. But while UNEP’s often politically ticklish environmental impact assessments are robust, security conditions, donor interest and a host of other factors can limit the temporal and geographical scope of their work. For the most politically problematic conflicts, field access and donor support may not be forthcoming at all.

The net result is that, while we know a great deal more than we did about the environmental consequences of conflicts, there are still huge gaps in data collection. The question we have been pondering, as we look to extend the work of the TRW Project, is how new remote monitoring and low cost field sampling methodologies can be devised. How these could help plug the knowledge gaps, how they could support the work of international organisations and humanitarian NGOs, and how they could help minimise the risks to communities from pollution. Work by our friends at the Zoi Environment Network on Ukraine, and by PAX on Syria, gives an indication of what is currently possible using local and online sources to remotely collate data on environmental risks. The biggest challenge will be data collection on the ground in what are typically insecure and unpredictable environments, and for that we are eyeing peacetime citizen science initiatives with interest.

Another question is whether improving how we gather data on these forms of environmental harm can also help change the behaviours of polluters – in this case militaries or non-state armed groups. Militaries can be reluctant environmentalists, as demonstrated by the blanket exemption for defence products in the Mercury Convention and the muddled system of defence exemptions under the EU’s REACH system. Nevertheless, increased documentation on the consequences of particular practices could help in the development of new behavioural norms.

We looked at the role that NGO monitoring bodies play in the implementation of environmental agreements and treaties on explosive remnants of war for a recent report that imagined what a new and more robust system of post-conflict environmental assistance could look like. Visibility and transparency were crucial to holding states accountable for their actions and in changing behaviours. Moreover, independent civil society organisations can have the freedom to act and react to developments more flexibly and with fewer political constraints than UN organisations. With the data they collect helping to augment more formal post-conflict environmental assessments.

In conclusion

It’s too early to tell whether the current talk among progressive governments will lead to greater protection for the environment and its inhabitants during and after armed conflict – the lawyers are still arguing over what the environment is and many influential governments are keen to protect their freedom to pollute. In some respects the big legal and political questions are irrelevant to the issue at hand – our need to better understand the impact that conflict pollution has on civilian lives and livelihoods.

In some respects the big legal and political questions are irrelevant to the issue at hand – our need to better understand the impact that conflict pollution has on civilian lives and livelihoods.

Just as we were inspired by the gulf between peacetime environmental and health protection norms, and those currently applied to conflict, peacetime approaches to environmental sampling, monitoring and assessment should form the basis of how we document and measure harm in relation to conflicts. We are very interested in developing collaborations with academia as we seek to identify and refine new methodologies to increase the quantity and quality of data on environmental risks from conflict. It’s the extreme end of assessment but we have a responsibility to document and understand the true impact of armed conflict on the environment and on those who depend on it.

(Infographic: credit Doug Weir)

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project, he studied Geology at Manchester Uni, Journalism at Sheffield Uni and has worked on the toxic legacy of conflict since 2005. Follow the TRW Project @detoxconflict or sign up to our Toxics Blog at www.toxicremnantsofwar.info If you’d like to learn more or to get involved, you can contact Doug at [email protected]