`Dr Cynthia Wang, Research Fellow, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick, UK

Sadly, it is not air but the air that is filled with substances and pollutants which we breathe in this modern world.

We live and we breathe in this world surrounded by the substance called air. Formless, colourless and odourless, air flows around us invisibly. Or is it so? From a certain perspective, “there is no ‘air’ in itself” (Choy 2011, 145). The air we breathe is composed of many atmospheric substances, from dust, oxygen, carbon dioxide, smell, particulate matters, and various gases (Choy 2011, 145). It is an accumulation of both natural and man made products, including toxic ones. And it often shows us its colour and smells, from the strange smelling yellow, white or black smoke of a refinery to the dark exhaust from a vehicle; and when it is filled with pollutants, dioxin, sulphur, chlorine … it can also be toxic and make breathing difficult for us, or even cause illness. Sadly, it is not air but the air that is filled with substances and pollutants which we breathe in this modern world. Existing in this mutually depended place while factories produce goods for us to consume, energy companies heat our homes, and cars make us mobile freely and faster, we breathe air that has been polluted by the producers of our consumption, and thus becoming “breathers” and “accrue the unaccounted-for costs that attend the production and consumption of goods and services, such as the injuries, medical expenses, and changes in climate and ecosystems” (Choy 2011, 145; Engelmann 2015, 441).

A personal experience

Two weeks after leaving China and back to the UK, I was still coughing occasionally, and my throat did not stop its annoying tickling no matter how much water I drank…… The reason: I stayed for about one week in Beijing researching about our project—Environmental Justice and Global Petrochemical Industry; and the feeling of breathlessness and coughing just followed me persistently. Depending on the weather – if there was wind blowing -I coughed less; if there was little wind, I coughed more.

Two weeks after leaving China and back to the UK, I was still coughing occasionally, and my throat did not stop its annoying tickling no matter how much water I drank……

My last day in Beijing was a heavy smog day and probably the main cause of my worsening cough that continued for two weeks after. November 27, 2015 was a gloomy winter’s day. Compared to the previous windy and chilly days, the sky looked murky and grey, and the city seemed cloaked in a thick cloud of haze. When I left my B&B in the morning, I decided to put on my facemask which had been sparsely used in the past days when there was chilly wind but comparatively good air. I walked quickly towards the metro, endless cars passed to and fro, and people were going about their business as usual …

Though wearing my facemask, which unfortunately turned out to be ill-fitting and thus ineffective in preventing my intake of pollutants, I started to feel very sick around noon when I arrived at an environmental organization after travelling by metro, and walking on the street for about half an hour; I felt breathless, throat irritation, and a seasick feeling. That night it became even worse and I started to cough unstoppably, while at the same time, I felt something clogging my chest and I needed to use some strength to pull my breath out … There must be problems with my lungs and other respiratory organs … How could it be? At the boarding gate, I turned on my laptop and started to search on the Internet. Out of the huge French windows, it was dark and gloomy, and one monster-like shadow of an aircraft slowly moved with orange light eyes …

PM2.5 in the air

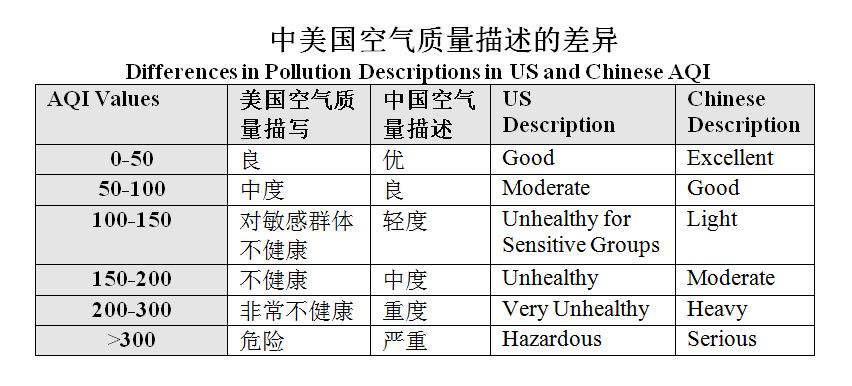

Thanks to the American Embassy’s initiative of disclosing the PM2.5 data on twitter since 2008, which later aroused a nation wide “I monitor the air for my country” and public pressure, the Chinese government were forced to monitor and disclose PM2.5 data in 2012. In today’s China, almost everybody knows something about air pollution, smog, and the quality of air can be assessed by checking PM2.5, the tiny particulates that make air dangerous to our health. Although psychologically well-prepared, I was still shocked to find out—the PM2.5 data for my last day in Beijing reached a hazardous level of more than 300 and sometimes more than 400 microgram per cubic metre (µg/m3) from early morning till almost midnight. The short-term standard (24-hour or daily average) of PM2.5 is 75 µg/m3 in China.

(Table credit: china dialogue)

PM2.5 is an air pollutant, a tiny particle with width less than 2.5 microns. A micron is a unit of measurement for distance and there are about 25,000 microns in an inch. Burning coal and vehicle exhausts can contribute to PM2.5. Although the World Health Organization sets a guideline value for PM2.5 at 25 μg/m3 24-hour mean, there is not a safe level of it (Raaschou-Nielsen et al. 2013). The higher level it is in air, the more harmful the air is to our health. It can travel deeply into our respiratory system and exposure to fine particles can cause short term health effects such as eye, nose, throat and lung irritation, coughing, sneezing, runny nose and shortness of breath. (Luckily it seems I only got some symptoms!) Exposure to fine particles can affect lung function and worsen medical conditions such as asthma and heart disease (Source: Department of Health, NY). The increase of PM2.5 also correlates to the increase of lung cancer (Raaschou-Nielsen et al. 2013).

A recent study published on Nature shows that outdoor air pollution, mostly by PM2.5, leads to 3.3 million premature deaths per year worldwide, predominantly in Asia (Lelieveld et al. 2015). Researchers from HK also found that acute air pollution had significant short-term health effects. More people died of cardiovascular or respiratory illness on days with bad air quality than they did on days of good air quality (Choy 2011, 147). In a conference about pollution and health I attended in China, it was argued that the complexity of causes to disease made it difficult to prove the link between certain disease to air pollution, nevertheless, researchers presented a comparison of clinical records of respiratory disease and smog days in cities in Hebei province and showed that heavier smog days resulted in more clinical visits of patients.

Researchers from HK also found that acute air pollution had significant short-term health effects. More people died of cardiovascular or respiratory illness on days with bad air quality than they did on days of good air quality (Choy 2011, 147).

Airpoclypcy: Air pollution beyond Beijing

The increase of PM2.5 in air does not only affect people’s health, it also affects climate change through changing the radiation balance of atmosphere (Kan, Chen & Tong 2012). A few days later when I was back to the UK and world leaders gathered in Paris to talk about climate change, reports about the heavy smog or “airpoclypcy” in Beijing appeared on almost all major world media, with photos of scenes of Beijing shrouded in heavy smog and people wearing all types of facemasks, from plain surgeon masks to sophisticated gas masks. And for the first time, Beijing announced “red alert” for air pollution, urged people to stay indoors and that schools be closed.

The fact is, in China, Beijing is not the only place where “breathers” have been suffering from the toxic air. Just before I went to China, in early November, PM2.5 reached one thousand in Shenyang, a city in north-eastern China.

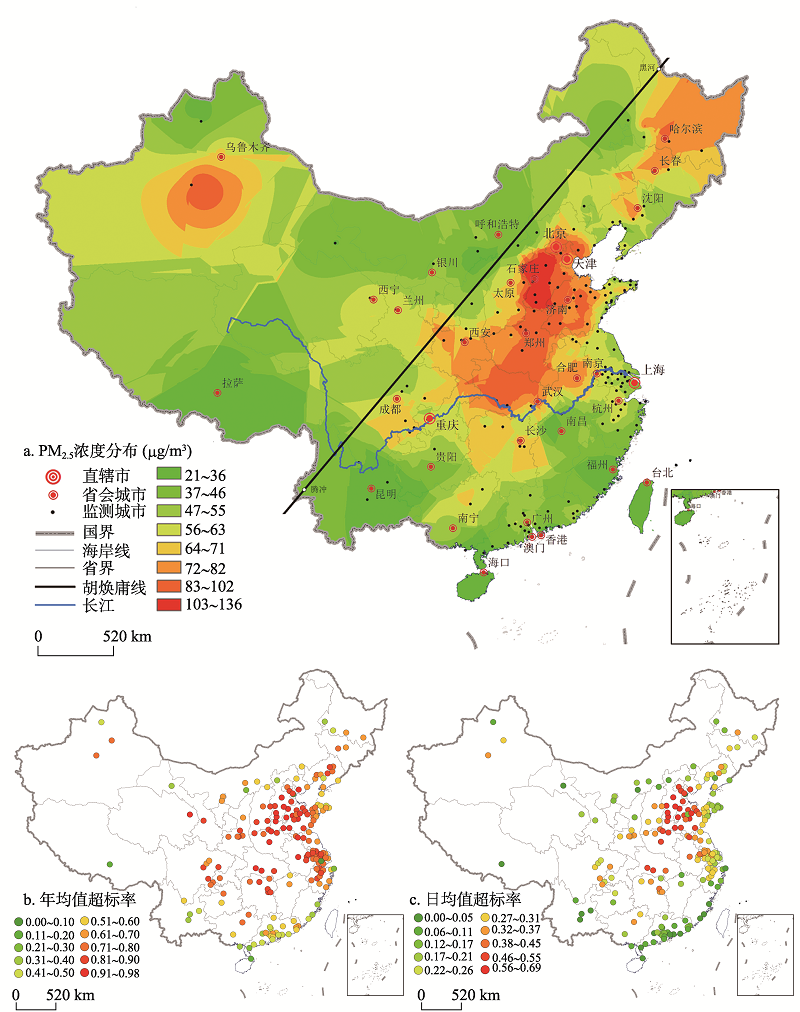

A study of air quality data of 190 cities in China shows that in 2014, based on the limit of 35 μg/m3 (long term standard in China), PM2.5 exceeded the limit in 90% of the cities, and the average over limit days was 246. In 44 cities, over limit days were more than 300, mostly clustered in Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei province, Yangtze River Delta, the middle part of China, urban areas along the middle reach of Yangtze River and Huai River. In seven cities (six in Shandong province and one in Hebei province), the over limit days reached 340; and in 105 cities, they were between 200 and 300 days. (Wang et al. 2015) Taking into consideration that the geographical size of China occupies more than 6% of the world’s land area, how much will its smog affect the world through climate change then?

(Source of the map: Kan, Chen & Tong 2012)

Who is not a “breather”?

Van Rooij and other China environment researchers pointed out that regarding environmental protection, a potential split might be happening in China where richer and more developed coastal and municipal areas have strict enforcement of laws to allow them to enjoy products and income from less developed areas where environmental pollution enforcement was lax. This has posed a potential risk for the occurring of regional environmental injustice over pollution challenges (Van Rooij et al., 2015). I have the same concern for fighting air pollution in China.

Being the capital city, with rich social, economic and political resources, it seems that Beijing’s air is of more concern than other places. Not only does it appear more in the news, it appears that to deal with the air pollution problem in Beijing, the central government has been seriously taking all measures, including initiating new policies, conducting extensive research, closing and relocating factories, and promoting Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Integration and regional coordination due to the interrelatedness of air pollution in these three places. Will air pollution in other places be dealt equally? Will factories be relocated to less developed places or simply closed down? And who will take care of those unemployed due to factories closing down for better air quality?

Individually, the burden of “breathers” is also different. While affluent residents use modern technology to filter homes, drive cars and wear sophisticated facemasks outdoors, how about people who have to calculate carefully about spending one Chinese Yuan for a steam bun or ten for an ordinary facemask?

Individually, the burden of “breathers” is also different. While affluent residents use modern technology to filter homes, drive cars and wear sophisticated facemasks outdoors, how about people who have to calculate carefully about spending one Chinese Yuan for a steam bun or ten for an ordinary facemask? Pathetically, it is the less affluent, who consume less, who bear the largest burden of the production of the consumers’ world—the toxic air. And most of all, to what extent does air pollution affect their social vulnerability—the impacts of harm to vulnerable groups due to social inequality (Cutter 2006)?

While people in northern China choked in smog in December 2015, thousand miles away in Paris, world leaders successfully reached an agreement for emission reduction to fight climate change, and China promised to make its CO2 emission at its peak by 2030 and also committed 20 billion Chinese Yuan to help developing countries dealing with the problem. China played its “[l]eading role as climate fighter”, hailed its official media. Hopefully, this will also help to solve its air pollution problem for hundreds of millions of “breathers” in China.

A year ago, in November 2014, China’s top economic planning body, the National Development and Reform Commission, said as China adjusted its economic structure and slashed coal consumption, by 2030, Beijing’s air would be clean and the sky would be permanent APEC blue – in reference to the blue sky during APEC when Beijing turned off most factories, and cars were limited on roads. One year later, in the conference about pollution and health, “it will take at least 20 years, or even 80 years for Beijing to solve its smog problem”, said a researcher who also pointed out that at present automobile exhaust is the major contributor to smog in Beijing. Beholding the millions of cars busy on Beijing streets, turning the expressways to parking lots with no head or tail on a regular basis and emitting unlimited exhaust; the endless expansion of the city with circles of circles of expressways and new construction sites; the quickly increasing, seemingly never-stopping consumption of materials; and higher and higher skyscrapers that help to trap the smog inside the city … To whom shall I listen to? The question is, toxic air that makes people breathless does not only exist in Beijing, but also in a large part of China and beyond, in Delhi, in Karachi, in Khorramabad, … “Who is not a breather?” How shall we start to reconnect the “intimate fabric of corporeality, including that of human becoming, to the seemingly indifferent stuff of the world that makes living possible”? (Whatmore 2014, 4; Engelmann 2015, 441) How shall we connect ourselves to the air we breathe? Clearly to put on facemasks is not the only answer. Shall we consider changing our ways of consumption then? And what shall we do regarding the more socially vulnerable? It is a time that all shall not evade but react.

(Featured image: credit Nicolo Lazzati)

Choy, T. K. (2011). Ecologies of comparison: An ethnography of endangerment in Hong Kong. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cutter, S. L. (2006). Hazards vulnerability and environmental justice. Routledge.

Engelmann, S. (2015). Toward a poetics of air: sequencing and surfacing breath. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(3), 430-444.

Kan, H., Chen, R., & Tong, S. (2012). Ambient air pollution, climate change, and population health in China. Environment international, 42, 10-19.

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D., & Pozzer, A. (2015). The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature, 525(7569), 367-371.

Raaschou-Nielsen, O., Andersen, Z. J., Beelen, R., Samoli, E., Stafoggia, M., Weinmayr, G., … & Xun, W. W. (2013). Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: prospective analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). The lancet oncology, 14(9), 813-822.

Van Rooij, B., Zhu, Q., LI, N., & Zhang, X. (2015). Pollution enforcement in China: understanding national and regional variation, at SSRN.

Wang, Z., Fang, C., Xu, G., et al. (2015). Spatial-temporal characteristics of the PM in China in 2014. (in Chinese) Acta Geographica Sinica, 70 (11), 1720- 1734.

Whatmore, S. (2014) Political Ecology in a More-than-Human World: Rethinking ‘Natural’ Hazards. Ch. 5 in, Hastrup, K. (ed.) Anthropology and Nature. Routledge. 79-95.